WASHINGTON ― As the administration of President Donald Trump readies a new crackdown on undocumented immigrants, the Supreme Court on Tuesday weighed a difficult case that could open federal courts to Mexican nationals whose family members are killed at the border by U.S. authorities.

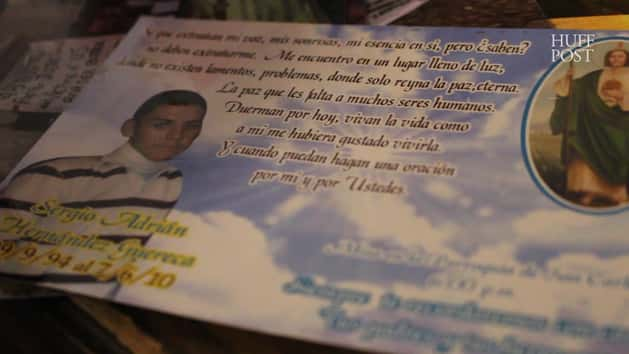

The sobering case of Sergio Hernandez ― a 15-year-old standing on Mexican soil when he was shot in the head by a U.S. Border Patrol agent from the American side ― found the justices wrestling with whether a non-citizen has any constitutional rights at the border. The answer will determine whether a federal law enforcement officer who violates a person’s fundamental right to not be killed can be sued.

“You have a very sympathetic case,” Justice Stephen Breyer told Bob Hilliard, the lawyer representing Hernandez’s parents, who didn’t attend the hearing. The family hopes the American justice system can help them press their civil rights claims against U.S. Border Patrol Agent Jesús Mesa, who killed their son in 2010.

According to the parents’ lawsuit, Hernández and other boys were playing in the cement river bank of the Rio Grande, which separates the neighboring cities of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Suspecting they were smugglers, Mesa approached the teens and moved to apprehend one. Some began to throw rocks, and Mesa opened fire in self-defense, according to a Department of Justice investigation. Hernández, shot from the opposite side of the river, was killed.

At the center of the justices’ concern during oral arguments in Hernandez v. Mesa was whether the court has the capacity to fashion a narrow rule that may provide relief to victims like the parents of Hernández ― without exposing the federal government to civil liability for other kinds of violence abroad.

“How do you analyze the case of a drone strike in Iraq, where the plane is piloted from Nevada?” Chief Justice John Roberts asked Hilliard. “Why wouldn’t the same analysis apply in that case?”

Hilliard, a longtime trial lawyer who has represented the Hernandez family throughout the case, struggled to give a straight answer on the proper standard courts should apply to cross-border shootings. In 2015, an appeals court ruled that the Constitution doesn’t apply to these kinds of incidents, essentially insulating Mesa and others like him from cross-border liability.

“We need to have a rule ... that can be applied in other cases,” said Justice Samuel Alito. “But you need to give us a principle that’s workable.”

Time and again, the justices and the lawyers referred back to Boumediene v. Bush, a landmark, post-9/11 precedent that established that foreign-born detainees at the Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba had a due-process right to challenge their detention.

Justice Anthony Kennedy was pivotal in that decision, which granted constitutional protections to the detainees. But on Tuesday, Kennedy didn’t seem so sure that civil liability should extend to federal law enforcement officers who fire across the border ― and suggested that the solution instead rests with Congress and the executive branch.

“You’ve indicated that there’s a problem all along the border,” Kennedy said. “Why doesn’t that counsel us that this is one of the most sensitive areas of foreign affairs, where the political branches should discuss with Mexico what the solution ought to be?”

There is no law on the books that allows litigants to sue federal officials for constitutional violations. But the Supreme Court in 1972 ruled that courts can hear these kinds of cases under specific circumstances. Kennedy cautioned that the court hasn’t extended this doctrine since 1988, and indicated that this may not be the right case to do it.

As legal twists would have it, Tuesday’s hearing was the first time the Trump administration presented an oral argument before the justices. The case began under the Obama administration, and Edwin Kneedler, the experienced lawyer who argued for the government, took a strong position against the Mexican teen’s family.

This case “gives rise to foreign relations problems, which are committed to the political branches,” Kneedler said.

At one point, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Kneedler if he had seen video of Sergio’s death on YouTube, which appears to contradict the Justice Department account that Mesa acted in self-defense. “Border policemen are shooting indiscriminately from within the United States across the border,” Sotomayor said.

If the Supreme Court rules that the Hernandez family can get no relief in federal court for Sergio’s death, they’d have nowhere else to turn. The Justice Department declined to prosecute Mesa in 2012, and the federal government rejected a separate request from Mexico to extradite the officer there for prosecution. Civil liability is the only avenue left.

Justice Elena Kagan suggested that because Hernandez v. Mesa is a “sui generis” case ― limited to an area where there’s no clear line of demarcation between Mexico and the U.S. ― that maybe the Supreme Court should try something more nuanced than an all-or-nothing approach.

“The dividing line isn’t even marked on the ground. Isn’t that right? You can’t tell on the ground where Mexico ends and the United States begins,” Kagan said. “I don’t know whether to call it a no-man’s land, but it’s this liminal area, which is kind of neither one thing nor another thing.”

Given the complexities of the case, it is possible the court may split 4-4, which would set no legal precedent. To avoid that result, the justices may choose to wait until Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s nominee to the seat of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, is confirmed. By then, the court may also choose to hold a new oral argument.

A decision is expected by the end of June.

Trump’s Department of Homeland Security on Tuesday declared open season on undocumented immigrants living in the U.S., saying it will hire thousands of agents to deport “removable aliens” who have been charged or convicted of even minor crimes.

Inside the courtroom, Roberts did something else to welcome the Trump era: He acknowledged the 84th attorney general of the United States, Jeff Sessions, who was in attendance. This recognition will be a part of the Supreme Court’s public record.