According to the United Nations, more than 7,500 people have died in Syria since the regime of President Bashar Assad launched a brutal crackdown against protesters last March.

As Syrian activists improve their techniques for transmitting photos and videos of the violence to the outside world, accounts and footage of torture, displaced families, and horrifying deaths have flooded the mainstream media. International condemnation continues to grow, yet Syria's future remains uncertain.

As Syria marks the one-year anniversary of the country's uprising, HuffPost World details some of the key players and events in Syria over the past 12 months.

THE BEGINNINGSyria was a relative latecomer to the Arab Spring. On March 18, 2011, protesters gathered in the southern city of Daraa after Friday prayers. Angered by the arrest and torture of children who had spray-painted anti-government slogans on a wall in the city the month before, demonstrators voiced demands for greater freedoms and political participation.

The protests did not initially demand the resignation of President Bashar Assad. Instead, they focused on the lack of basic freedoms in the country, the monopoly of the Baath party, Syria's security state apparatus and abuses by the elite, Patrick Seale, author of the book The Struggle For Syria, explains in Foreign Policy. Yet security forces responded brutally, firing live ammunition and tear gas at the crowds and killing several protesters.

As anger over civilian deaths grew and protests spread to other cities, Assad offered a series of concessions -- officials implicated in the violence would be fired, a number of political prisoners would be released, and the country's state of emergency would be lifted. The regime maintained its innocence, however, and claimed that foreign agents were to blame for the unrest.

PROTESTS AND VIOLENCE SPREADThe spring and summer of 2011 were characterized by a steady stream of protests -- often on Fridays after prayers -- and the Syrian government's subsequent violent response to the gatherings. Security forces cracked down hard in the cities of Homs, Hama, and Latakia.

The violence reached new heights toward the end of 2011 as the conflict appeared to militarize. "You now have on average as many as forty people being killed a day. That's one dynamic; the killing has increased, particularly since the Arab League monitors arrived at the end of December," Council on Foreign Relations Middle East expert Robert M. Damin explained in January 2012.

A growing number of defectors -- loosely organized in the Free Syrian Army -- staged guerrilla attacks against security forces. In December and January, two separate bombs targeting security forces killed dozens in the Syrian capital Damascus. While the

'MASSACRE' IN HOMS

In February 2012, regime forces launched a brutal assault on the city of Homs and the rebel-held neighborhood of Baba Amr in particular. Bombs and rockets rained down on the city for weeks, killing hundreds of people -- many of them civilians. Government forces eventually retook control of the city, driving the Free Syrian army out. British photographer Paul Conroy described the siege of Homs as a "massacre." Talking to Sky News, Conroy said Syrian forces were "systematic in moving through neighborhoods with munitions that are used for battlefields." He added that "men, women and children" were "cowering in houses" and "beyond shellshock."

The regime's strategic victory in Homs was followed by attacks on the rebel strongholds of Idlib and Daraa. "Shelter is hard to find when mortars take out entire sides of buildings," Al Jazeera's Anita McNaught reported from Idlib. "Syrian army tanks and army personel carriers fire randomly and indiscriminately into the streets," she wrote.

SECTARIANISM IN SYRIAThe events in Homs illustrate the rise of sectarian conflict in Syria. Commentators have observed that the country may be headed for civil war.

The majority of Syrians belong to the Sunni Muslim community, but the country also has significant Christian, Shiia and Alawi groups. President Bashar Assad belongs to the Alawi community, a sect that split from Shia Islam and makes up about 12 percent of the population in Syria. Alawites hold many key positions in the Syrian government.

THE REGIME'S TAKE"We don't kill our people... no government in the world kills its people, unless it's led by a crazy person," Bashar Assad told ABC's Barbara Walters in an interview. Assad defiantly denied ordering a crackdown against protesters and claimed that most of the people killed were either regime supporters or security forces. Instead, Syria blames Israel and the West for the conflict, accusing "armed gangs," "terrorists" and "saboteurs" of instigating violence.

THE OPPOSITION"As long as Bashar al-Assad is in power in Syria, the future of Syria is going to be unfortunately a very bloody one," former U.S. diplomat Dennis Ross told Reuters.

It is unclear who would fill the void in the event of the fall of the Assad regime. "Syria's opposition is divided," Robert M. Damin writes for the Council on Foreign Relations. "You have the Syrian National Council. You have another group called the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change, which represents many of the opposition groups inside Syria. And there is a very strong division between them. They have tried to come together and overcome their differences but they have not succeeded; Syria is a very heterogeneous country."

Similarly, reports suggest the Free Syrian Army is far from a unified organization with a single command structure. According to the BBC, the FSA was formed in August 2011 by former members of the Syrian army and led by former air force colonel Riyad al-Assaad. "Col Asaad claims to have 15,000 men under his command and that soldiers are defecting every day and being assigned tasks by the FSA. However, analysts believe there may be no more than 7,000," the BBC writes in its 'Guide To The Opposition.' "It is now an umbrella group for civilians who have taken up arms and militant groups."

Al Jazeera's Nir Rosen describes the FSA as "a name endorsed and signed on to by diverse armed opposition actors throughout the country, who each operate in a similar manner and towards a similar goal, but each with local leadership."

INFORMATION DISSEMINATIONWhile the U.N. estimates that 7,500 people have been killed in Syria's uprising, activists estimate that hundreds more have died.

Media access has been severely limited in Syria, Internet access is restricted, and local journalists have been suppressed as the opposition and regime present competing narratives of the state of the country.

Activists and citizen journalists have distributed hundreds of photos and videos online that often show dead or injured children and civilians, mutilated bodies, or destroyed neighborhoods. Yet verifying the content of these reports remains nearly impossible. "Plenty of information is coming out from Syria, but the difficulty we find is in verifying the information," said Soazig Dollet, head of the Middle East and North Africa desk of Reporters Without Borders to Al Akhbar. "Because of the state’s strict control of traditional media in the country, social media has become our main source of information. However, the question of who is sending out this information remains unanswered," he told the newspaper.

Reporting from Syria has proved extremely dangerous. AP photographer Rodrigo Abd recounted his time in Syria: "Explosions illuminated the night as we ran, hoping to escape Syria after nearly three weeks of covering a conflict that the government seems determined to keep the world from seeing. Tank shells slammed into the city streets behind us, snipers' bullets whizzed by our heads and the rebels escorting us were nearly out of ammunition. It seemed like a good time to get out of Syria."

While Abd safely reached Turkey, several foreign reporters did not make it out of the country alive. French TV journalist Gilles Jacquier died in January 2011 in Homs. A sniper killed activist and online journalist Rami al-Sayyed on February 22. One day later, American war correspondent Marie Colvin and French photojournalist Remi Ochlik were killed by shelling in Homs.

INTERNATIONAL REACTIONMost of international community's response to the bloodshed in Syria has been harsh. Barack Obama repeatedly has called on Assad to step down. U.N. chief Ban Ki-Moon has described the violence in Homs as "unacceptable before humanity." French President Nicholas Sarkozy called Assad a murderer. Turkey, once Syria's ally, has upbraided Assad, and both the U.S. and the European Union have imposed sanctions on his regime.

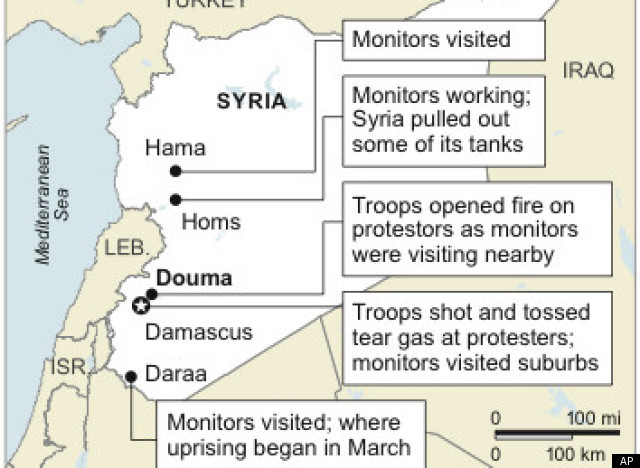

The first significant international attempt to end the bloodshed in Syria came from the Arab League. In November 2011, the organization of Arab states negotiated a peace plan with the Assad regime that called for an immediate end to the violence. The agreement also stipulated that monitors from the League's member states would observe the regime's compliance from inside the country. The associated monitor mission, and the Arab League peace plan, failed as the Assad regime intensified its crackdown during the observers' presence and the death toll rose dramatically.

As international pressure on the Assad regime increased and the failure of the League's monitor mission became clear, the organization presented a U.N. Security Council resolution that proposed to end the conflict through the resignation of the president. The resolution was approved by 13 of the Security Council's 15 members, but was vetoed by China and Russia. Moscow has stepped up as Syria's main supporter diplomatically, blocking any possible international action in the United Nations Security Council. The Kremlin also upheld arms deliveries to the country, arguing that Damascus needs the weapons for national defense and national security purposes.

MAP OF SYRIA:

TIMELINE OF EVENTS:Warning: Contains graphic content.