Only in Japan, I suspect, would people exult in "2.5-dimension" characters, as they call them, shimmering between the virtual and the actual; only in Japan, in fact, would people aspire to becoming cartoon characters (as they do in "cos-play" cafes, where young women dress up like figures from a manga comic). Being an animated figure, in several senses, seems the dream of many a Japanese. The government sends out Kitty (the mouthless heroine of "Hello Kitty" fame) and Doraemon (a 22nd century, blue robotic cat) as official "cultural ambassadors" for the country; the Tokyo Police Department, the national tax office and even the nuclear industry all present themselves through perky cartoon mascots, as if they could defuse harsh realities with an adorable, chirping character called "Peepo."

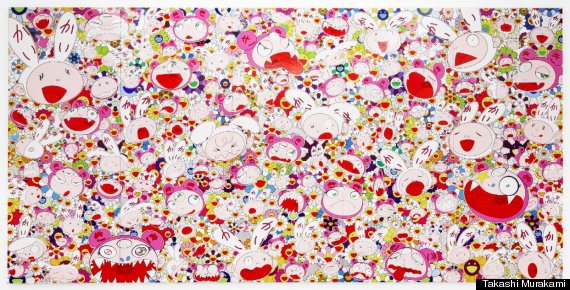

Every time I look at the work of Takashi Murakami, I see both the super cute, charming surfaces for which Japan is rightly famous and all the demons that peek out behind them. He dreams up lovable blobs and dolls and oversized cuties to ask his compatriots what might be the cost of holding onto such childish things.

It's as if this artist born just a generation after a devastating war and the dropping of two atomic bombs on his land is wondering why his country attempts to turn that trauma into comic book faces -- the wartime emperor was celebrated for his love of his Mickey Mouse wristwatch -- and why a land of centuries of Shinto and Buddhism is so ready to shrivel into obedience and self-effacement. A piece like "Warp" makes this almost explicit -- where does Japan end and the bright, new, relatively unstoried world of America (and Americanized Japan) begin, it might be asking. But even more in a quintessential Murakami work, featuring his very own cartoon creation, DOB, we realize that the very brightness and determined cheerfulness of Japan's modern surfaces are no protection at all against the spookiness of a mushroom forest redolent of some ancient underworld.

Murakami is a realistic chronicler of the flight from the real. In other words, and much as Andy Warhol decided that he would give modern America exactly the glut of mass production and mass celebrity it seemed so intent upon -- with a vengeance -- so Murakami might be offering Japan precisely the images it loves, but over-the-top, extreme; a culture of perfect miniatures blown up into Thanksgiving Day parade balloons. He turns his country's smiley faces inside-out.

Many loudly talk of how Murakami has directed Kanye West videos, designed Louis Vuitton bags and turned out candies, stuffed animals and Monopoly sets, branding himself as if to blur the distinction between marketing and art. But what he's really about is the loss of context and history in Japan (or anywhere), and the global state of not knowing whether one's here or there. At one point, looking at his art, I decided to compare his birthdate with that of David Foster Wallace, the late American novelist who offered the same kind of anguished, droll, ironic --wounded -- take on young America, and its po-mo innocence and search for meaning. I wasn't surprised to find that both were born in the same month -- and in the same year (February 1962) -- and so were heir to some of the same agonies.

****

Japan has always been a culture guiltlessly devoted not to the either ors that define our society, but to what you could call "both-and"s: at weddings, young women change clothes two or three times, from haunting white Shinto hoods to Grace Kelly-worthy white confections to chic little black dresses from Chanel. In Zen practice, sacred and profane, Nirvana and Samsara, are essentially one -- so long as you can see both in the right light. It's this zesty freedom from distinctions that makes individual Japanese spaces often exquisite and impeccable, even as the overall effect of a typical Japanese city is a kind of riotous visual gibberish, comparable to that of someone speaking French, German, Chinese, Creole -- and Japanese -- all at the same time.

Murakami is the consummate artist of this both-and sensibility in its post-war form. He will join Buddhist sculpture to a cartoon culture and see a Shinto spirit inside a "pocket monster." He will be both keyring-maker and learned Ph.D., who can trace the beginnings of manga art back to its origins centuries ago (it was Hokusai who first popularized manga in the sense we know of now). Here is someone who pushes a very old tradition against the latest, "super-flat" surfaces (the name itself suggests America's poppy influence) to show us a culture that's lost a sense of whether it's a cool global teenager or stuck in an old person's home.

Put another way, I was not surprised to read that Murakami (who holds his doctorate in Nihonga, that style of classical Japanese painting that draws on elements of Western art) leads all the workers in his factory in callisthenics every morning, just as the most Japanese of Japanese company heads would do -- even as he remains in constant contact with his branch office in Long Island City. When he was setting up a major exhibition at the Asia Society in New York, in 2005, as the New York Times reported, an American colleague suggested the title, "Japanese Pop Culture Explosion." In its place, Murakami, bright with subversions, came up with the perfect alternative, "Little Boy," referring at once to the little boys of Japanese nerd culture, Douglas MacArthur's notorious remark that Japan was a land of "12 year-old children" and, most terribly, the nickname of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. The name sounds cuddly and cute when first you encounter it, and then it explodes in your face.

It's that one-two punch that speaks for his deceiving surfaces, at once "easy and difficult," as he puts it, and apparently designed to amuse until they begin to disturb (think also, for example, of the very popular Japanese novelist of the same generation, Banana Yoshimoto. Given that her father is a celebrated poet and critic, the name under which she publishes her books is somewhat akin to "Passion Fruit Eliot"). Watch Murakami politely bowing before the camera as he takes you on a video tour of a show of his at the Guggenheim, and you see a figure at once amiable and seditious, open and unpersuaded. He's the fool in a Shakespearean play who keeps posing simple-sounding questions that ultimately suggest a wisdom greater than that of any of the characters ostensibly in power all around him.

*****

It's not always easy for an outsider to understand how deeply innocence is prized in Japan, even if (in manga and anime) it's always being violated. No baseball players are more ritually revered than the high school players who take the field twice a year at Osaka's Koshien stadium, and whose shaven heads and unguarded fresh faces give them the look of apprentice monks. Every sumo wrestler throws out purifying salt before embarking upon his three minute bout. You often hear in Japan the phrase "Loli-com" (short for "Lolita complex"), and it could refer to the whole nation, fixated on dewy and wide-eyed young boys and girls, who fill TV shows, vending-machine magazines and porno displays in ways that would unsettle most of the rest of us. Audrey Hepburn, the last word in pertness, will always have more fans in Japan than Angelina Jolie; Hello Kitty might be Felix or Jerry-chasing Tom, or especially Fritz the Cat, curiously reversed.

Murakami has always seemed too shrewd to go along with this cultivated innocence, and determined to place a kind of time bomb under a society intent on hiding out from reality. He gives us dreamy, Peter Max-y psychedelic colors -- there's "Warp" again, redolent of the explosions of the '60s -- and nightmare titles that undercut any notion we may have of love and peace and understanding. He offers up a classic version of wide-eyed guilelessness --Nurse Ko2 -- but so sexualized it becomes the opposite of soothing. He affects the ways of the nerd -- sporting a half-cool ponytail, gobbling down noodles, as if pulling an all-nighter -- and yet he takes the nerd's fantasies into places where even the geek may blanch and turn away.

None of this is new, of course -- that is part of his point (he's erudite enough to point to the way 17th century Japanese landscape paintings prefigure the flatness of comic books). But ever since World War II, Japan has seemed particularly at a loss as to how much it should be guided by ancient China, how much by modern America. If you read contemporary Japanese fiction, you will find every other story describing kids acting out, if only because their fathers are constantly absent and their mothers are caught between the old ways and the latest stuff. It's not hard to see the whole country as the bewildered child of a G.I. father and a local woman who knows she doesn't want a Japanese future, but isn't sure if she really feels at home with an imported one.

Murakami himself has given voice to this, as if to suggest that his is an art for, by and about slightly mutant infants. "We have to realize we are handicapped," he's said of Japanese society, "and we don't want to realize it. We know the U.S. is our father. We thought we were children, but we are handicapped people. We need help." His art might be trying to shake his compatriots up and forcing them to step out from behind their shy self-denials; each new flourishing of bling, or enormous canvas, each new exhibition impenitently entitled "MURAKAMI EGO" has the sound of a startled child trying to wake up his parents as the house burns down around them.

Though his intention might have been satirical before, in the wake of the tsunami and nuclear meltdown of 2011, Murakami has been trying, with seeming sincerity, to extend a sympathetic hand to his countrymen, and thinking about what religion can offer to a country that seems not just lost but deeply wounded. I went up to the devastated Fukushimi Dai-ichi nuclear plant, seven months after the events of March 2011, and as I heard the Beach Boys sing "I Get Around," again and again in a deserted tea room surrounded by laundromats, I felt more than ever how much Murakami's unsettling provocations were needed in the land where I've lived now for 27 years.

Before I really studied his work, I had lazily imagined that he was telling the story of mixed-up, post-war Japan almost as if he were part of the Three Murakamis (to invoke a cartoony tag he'd perhaps enjoy). Two of the most popular novelists in Japan in recent decades, after all, both happen to be called Murakami (though none of the three are related): Ryu Murakami grew up next to an American base (as Takashi Murakami did) and seemed at once to ingest everything that was coming into Japan, and to spit it out, in novels called Almost Transparent Blue, 69 and War Begins Beyond the Sea (he's still a wildly popular TV personality who plays the drums and inspires movies); Haruki Murakami has found huge success across the world by giving us globally generic stories of an amiable drifter in the suburbs whose life is entirely easy and pleasant, but who can't help sensing that his real home is amidst his troubled and mysterious dreams.

The name "Murakami" means "Above the Village," which seems perfect for three radical artists who are positioned high above the great communal urban setting of Japan and trying to figure out how much they'll be defined by their grandparents, how much by their kids (the ever more global conundrum). But as I looked more closely at Murakami's canvases, I saw how much he was also in tune with Haruki Murakami's great opposite, Hayao Miyazaki, the animator whose works ("Spirited Away," "Princess Mononoke," "My Neighbor Totoro") try to remind Japan of all the spirits that, in the Shinto vision, still inhabit every last river and tree and even desk. It's not that we are or should be like cartoons, Miyazaki suggests, but that even the things that seem inanimate have souls, the ability to bleed. That's what I see now when I look again at a Murakami work such as "My arms and legs rot off..." It's not just an elegy for Japan, and for the 2.5-dimensional life the country has sought out for itself; it's also an unusually naked and poignant look at a society -- at individuals -- who find themselves alone, in the forest, smiling as their world collapses around them.

Adapted from an essay in the forthcoming catalogue documenting the contemporary art collections of philanthropists Eli and Edythe Broad. On May 29th, Pico Iyer will be in conversation with Takashi Murakami in Los Angeles as a part of The Broad Museum's Un-Private Collection talk series, which features cultural leaders and artists in the Broad collections. The talk will also be streamed live at www.thebroad.org. The Broad is a new contemporary art museum being built by the Broads in Los Angeles. The museum, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, will open in 2015 and will be home to the more than 2,000 works of art in the Broad collections. For more information on Eli and Edythe Broad, the new museum, and the upcoming conversation with Pico Iyer and Takashi Murakami, visit www.thebroad.org.