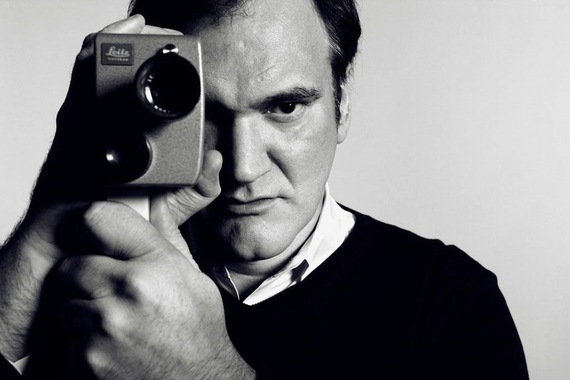

The new Sight & Sound features my ten-page interview with its February cover star, Quentin Tarantino, and they have graciously allowed me to excerpt a portion of the extensive Q&A here. This is a nice chunk of it, but there's so much more in the magazine, from getting to know his characters, to the Roadshow appeal of The Hateful Eight and themes in the movie, to movie violence, to Leonardo DiCaprio's character in Django, to shooting on Ultra Panavision, to his own theater in Los Angeles, The New Beverly (shout out to Clu Gulager in the issue), to his love of old film prints, to interesting thoughts and facts about his past movies, and much, much more. Dig in and read it all via the magazine. For now, check out these choice moments from the interview.

"There was a whole lot of speculation from some people about this whole 70mm thing, as in, that's really great, but it's just this set-bound parlor piece, so isn't it just a big old fucking waste of time and money? And, I think that's a shallow view of how 70mm can be employed. It's not just to shoot the Seven Wonders of the World, the Sahara desert and mountain ranges. You can do more than just shoot weather.... I've shot a lot of movies with Sam Jackson but I don't think I've ever gotten the close-ups of him that I've got in this. You drink in the chocolate of his skin, you swim in those eyes... And also, it becomes about the dialogue." -- Quentin Tarantino

KM: The Hateful Eight: This is another western and, in many ways, like Django [2012] a political one. You've said that you originally didn't think of it politically in terms of current times and, yet, the movie has become that. The western genre is often an effective way to explore psychological, political and cultural themes, and through the history of cinema... would you agree?

QT: I've always felt that actually. I've always felt, and, especially if you read any of the really interesting subtextual criticism on Westerns, especially leading into the late 60s and into the 70s, westerns have always done a pretty good job reflecting the decade in which they were made without seemingly trying to. When westerns were probably at their most popular, during the 50s, they definitely put forth an Eisenhower-esque America. And it was also an America and an American west that was flush with American exceptionalism -- having just won World War II and the advent of the suburbs. That was very important to westerns back them. And even, in an interesting way, while they weren't bold enough in the 50s to deal with the race problem in America, i.e., between blacks and whites, since the race problem between Indians and whites was long since over with, they actually tried to somewhat deal with black and white issues via Indian and white issues. Like [Delmer Daves's] Broken Arrow [1950] ... In the case of Broken Arrow, Jeff Chandler, in particular, became a big box office draw for Black people in America because of his performance of Cochise in that film.

And, that followed suit with the first half of the 60s, which was basically the 50s part II. But in 1966 on, things started changing and spaghetti westerns went a long way toward doing that: the stylization, the use of music, but also the counterculture. So by '68, '69, '70 and '71, you had the hippie westerns, the counterculture westerns, whether they be Kid Blue [1973] or The Hired Hand [1971] or Zachariah [1971], things like that. The 70s, particularly in America, was one of the best times for the western. And the changes went further into the 70s; it increased as the decade went on, [in terms of] the true "anti-western." Because so many of the different westerns at that time dealt with the Vietnam War, in one way or another.

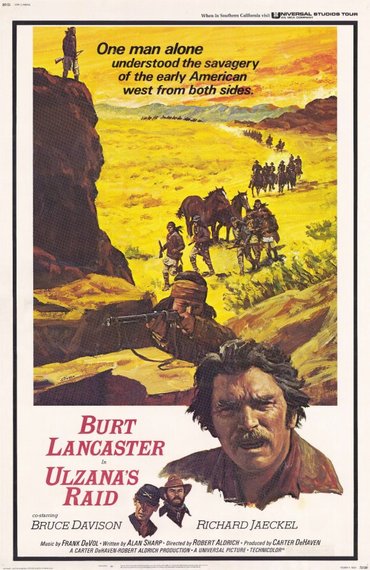

KM: Like Robert Aldrich's Ulzana's Raid [1972]...

QT: Yes. Ulzana's Raid is the perfect example. Most of the Vietnam metaphor movies don't work quite as well any more because you're thinking, "Well, why didn't you just make a movie about Vietnam?" Ulzana's Raid actually still completely works as a Vietnam metaphor, because that was underneath it, and what was on top of it was a war movie about the American Indian wars, about the calvary fighting a nomad army, about how warfare like that is done. So it was legitimately a war movie about those times and taken seriously as a war movie in a way that most movies dealing with that subject didn't do. But you had a situation during that era, of, 'We can't trust our government for getting us into this war, they said it was this; it wasn't, we don't trust them ...' all the different hypocrisies that kept rearing their ugly heads leading to Watergate.

And so one of the things that was so interesting about that new Hollywood time period, and particularly reflected from 69-74, not only did the happy ending go away, it was the vogue to have the cynical ending -- the cynical, hypocritical, tragic ending. We were cynical about America and these movies just confirmed our cynicism about the subjects. And because we were cynical about America, you see movies that rip down the statues that we had built. So you see Frank Perry's Doc [1971], which skewers the Wyatt Earp legend. And then, after everyone from Roy Rogers to almost everybody else playing Jesse James, you have Robert Duvall playing Jesse James in The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972) where he's a homicidal maniac; it's completely horrifying. And then Michael J. Pollard in Dirty Little Billy [1971]...

KM: Billy "was a punk"

QT: [Laughs] Exactly, right. And Michael J. Pollard looking like that one famous photos of William H. Bonney, more than Robert Taylor ever did. [Laughs]. The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (is miles away from the Tyrone Power Jesse James movie. And leading to the most overt Watergate western, Posse [1975], directed by Kirk Douglas, starring Douglas and Bruce Dern; written by William Roberts, who wrote the screenplay for The Magnificent Seven [1960].

KM: And in terms of The Hateful Eight, recently, in your real life politically, it's interesting because you've had all of this...

QT: Brouhaha [Laughs]

KM: Yes. Brouhaha with the police, which became ridiculous. No one with any sense can be on board with their statements and methods towards protesting you -- the intimidation.

QT: Oh, yeah I know. It's been an interesting four weeks as far as that was concerned [Laughs]. The first week, everyone was piling on me. And then, the second week, I react to it and that was kind of interesting because all of a sudden, everyone on TV ended up having some sort of say about it, so I thought, "Wow, this is good that this much about police brutality is being dealt with and is in the news so much." And then the cops do themselves no favors by issuing genuine threats. The funny part about it is, people ask, "Well, are you worried?" And of course I'm not worried. At the end of the day I don't feel that the police are some sort of sinister Black Hand organization that singles out private citizens to fuck over. Nevertheless, a civil service entity shouldn't even be putting out threats, even in a rhetorical nature, towards private citizens and the fact that they're using language that makes them sounds like bad guys in an 80s action movie doesn't help their cause any. In fact, it almost makes my cause. Almost sounds as if they're out of touch. [Laughs]

KM: About [Jennifer Jason Leigh's Daisy Domergue] character: It might be a bit controversial for some because she gets smacked around a lot; she's taking it as tough as anyone else and that she's endured this before is part of who she is...

QT: There's an interesting aspect to that. No one's yet to nail me personally or in person about that aspect: that she takes so much abuse in the course of the movie and I'm almost looking forward to it because I'm curious exactly where they're coming from. You feel it ripple through the audience the first few times she gets the shit beat out of her. And you feel it in old movies too, you know, when the girl is hysterical and the guy just smacks the shit out of her: "I'm sorry honey I hated to do that but you're off your nut." [Laughs] But that's different. When Daisy is really hit the first time, she's saying rude shit: "You're not going to let that nigger in here?" And he cracks her skull.

KM: And the first time he hits her it follows with such a powerful close-up. Her slightly vulnerable and then, angry face. You have a lot of mixed feelings when you see that shot. You do feel for her. You've just met her. How despicable is she?

QT: Oh, I think it's one of the best shots. And, yes, yes, all of those questions are left to be answered. She's definitely a rude, hateful bitch, that's for damn sure, but his response is so brutal. He didn't just punch her; he takes the butt of his gun and cracks her in the skull really hard. And that close-up, yes, she's fantastic in the close-up. And you realize just how bad he hit her when the blood starts dripping down her face. But you have this feeling of, "Ohhh... this is going to be that kind of movie" and it's just starting off. And nobody's not going to be on Daisy's side after that, in some way or another, because you'll think, John Ruth is a brutal, brutal man. And you're right: John Ruth is a brutal, brutal man. If the movie were on John Ruth's side at that point well, then, maybe somebody might have a more righteous pen, writing a subtextual article about it. But the movie is obviously not on John Ruth's side at that point. And especially in the stagecoach... But then things change as they go on. It's part of the way the story works; anything can happen to any one of these eight characters. The idea that I would give a female character some blanket coat of invincibility in that regard is just a ridiculous concept; it would be detrimental to her and to the sex of her character if I played any favorites.

KM: One thing I find interesting about the old western shows and that time in television in general, was that it was this period in television during which some seasoned, interesting directors like Joseph H. Lewis, were directing episodes of The Rifleman while newer guys coming in, like Robert Altman, was directing Bonanza.

QT: Yep. Bonanza, Combat!...

KM: And then you had John Cassavetes starring in Johnny Staccato [1959-60] and Ben Gazzara in Run For Your Life [1965-68] and then an old movie star like Barbara Stanwyck leading The Big Valley [1965-69]. And, on top of that, you'd see all these unique, particular talents with guest stars like Warren Oates, Warren Oates doing all kinds of things...

QT: Him and Bruce Dern were sidekicks in Stoney Burke [1962-63] the Jack Lord rodeo show.

KM: Yes. A show with great cold openings... And then The Virginian [1962-71]...

QT: [Laughs] Yeah. I'm a huge fan of, in particular the William Whitney episodes of The Virginian. His episodes are really terrific because he actually had the budget that he didn't quite have while at Republic. They were like 90-minute movies and were actually released as movies overseas. But. Sam Fuller did a magnificent episode of The Virginian ["It Tolls For Thee," 1962], which he wrote and directed. It's a Sam Fuller episode in every way. It stars Lee Marvin as the bad guy who kidnaps Lee J. Cobb and the episode is all about that kidnapping. Marvin and Fuller wouldn't work together again until The Big Red One. It's Sam Fuller dialogue from beginning to end. And, I have to say; I took one line from it for The Hateful Eight. I won't say the line in my movie but I'll say the line from The Virginian: Lee Marvin runs an outlaw gang and then another guy in the gang, a guy named Sharkey, starts talking to the gang to try to get them to forget about Lee Marvin and Lee Marvin just shoots him in the back. Lee Marvin says, "One measly bullet and there goes the problem of Sharkey." [Laughs]

KM: The Hateful Eight, it's not timeless, but because there's a sometimes-modern subtext to the characters, and timeless issues we're contending with today, it doesn't feel simply rooted in the past. Looking at people from the past, they often are more radical looking than we think, in terms of appearance, especially people in the west...

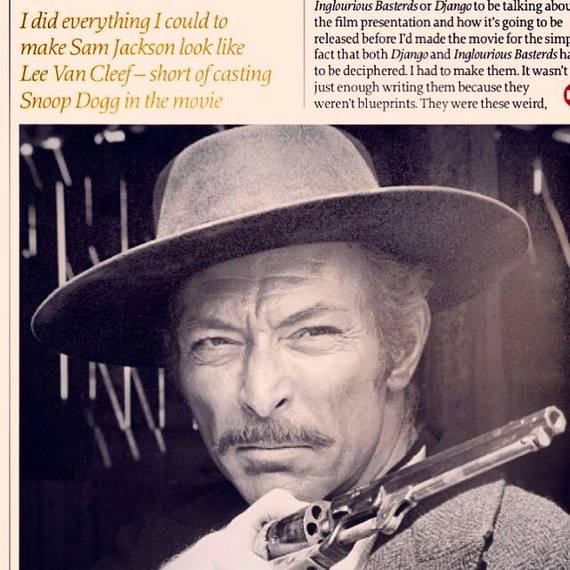

QT: There definitely is that. There is a spaghetti western-ish patina to the characters, for lack of a better adjective. Most of the really interesting characters in the Spaghetti Western have a comic-book feel, as if they were drawn. And the costumes themselves have this comic-book artist kind of fetishistic quality to them. Then you think of all of Leone's films and most of Sergio Corbucci westerns were done by Carol Sini, who was the costumer designer and the production designer, and he did the props. Can you imagine the guy who came up with the Django costume and Angel Eyes' costume and the Man with No Name costume he, also, like, found the circular graveyard in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly [1966] or that fucking rope bridge over the quicksand or the fucking muddy town in Django? I mean, what a genius! That level of work is almost unfathomable. I did show Courtney Hoffman, my costume designer, a bunch of Carlo Sini movies and she got it. The character's costumes have to pop before the characters. With Sam Jackson that's easy because he comes with a big personality on his own. He fills out that batwing, yellow underlining just perfect [Laughs].

KM: In terms of actors, I know that two of your favorite actors are Aldo Ray and Ralph Meeker. Is there anything about an actor, or those two guys in particular, that informs a cinematic aesthetic? Just an actor and a style, the world around them...

QT: Well, actually, literally in the case of Bruce Willis in Pulp Fiction [1994] it did. What I liked about Bruce Willis is that he reminded me a 50s leading man. He still has that quality now. He reminded me of a Ralph Meeker, Aldo Ray, and Brian Keith kind of man. I went to his house and we did actually watch one print of an Aldo Ray movie, we watched Nightfall [1957].

KM: A great movie. And with an evil Brian Keith too. They have great banter in that movie.

QT: They have fantastic banter. And Brian Keith is excellent. I'm a big fan of Brian Keith in all of his Phil Karlson movies too. With the rise of the great 70s leading man, with the rise of Elliott Gould, Jack Nicholson, Donald Sutherland, Dustin Hoffman and George Segal, the one thing that took a hit were people like that Brian Keith leading man.

KM: Who are the actors you've most have wanted to work with?

QT: Obviously, Ralph Meeker and Aldo Ray are two of them. Michael Parks, in his day. I worked with him but in his day would have been nice. Robert Blake in his day. I would work with Robert Blake tomorrow, now would be nice too. I would have loved to work with Bette Davis in her day or out of her day. In the early 60s, in the 40s, 30s to Burnt Offerings [1976] time. All good. TV movie time. All good. I'd love to work with Al Pacino now, I just saw him in the new Mamet play and he was terrific. I might even want to work with him now more, even more than his Serpico [1973] days. I would love to have Al Pacino rip snorting through my dialogue.

KM: We've talked about 70s movies; where you feel like movies like that aren't made anymore. That it really feels like it takes place in 1970. One movie from the 70s that I always find amazing did so well, given one famous, disturbing sequence, is Deliverance [1972] ... Could anyone make that film today? Like that?

QT: Oh, I know. I saw Deliverance in 1972 in a double feature with The Wild Bunch [1969] at the Tarzana Movies, the Tarzana Six, back when it was a big deal that six theaters were in one place. And recently I've been writing a piece of film writing, just for my own edification, and I've been going through some of the films and imagery that I saw in 1970 and 71. So, in 1970, I saw, at the counterculture Tiffany Theater, at age 8, a double feature of Joe and Where's Poppa? That same year I saw a double feature of The Owl and the Pussycat and The Diary of a Mad Housewife. In 1970 I saw Richard Harris be hoisted by his nipples in A Man Called Horse. In 1970, I didn't see Women in Love but I saw the trailer for "Women in Love" that had the naked wresting match between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates. And in 1972, forget about all the things I saw in The French Connection, I saw the slow motion bullet kills in The Wild Bunch only to see Ned Beatty fucked in the ass in Deliverance.

KM: Wow.

QT: That movie, rocked my world as a kid. When I saw the butt-fucking scene in Deliverance, I didn't know what sodomy was, as a kid. What I did know was that he was being humiliated. And I did know those guys were fucking scary. That's what I knew. Well, I was right. He was being humiliated, he was being subjugated by really scary people who were imposing their will over him. That is what it was about. It wasn't about the sex. The one part that would freak adults out went over my head but I actually got it [what it meant]. And that made me not want to go camping. [Laughs] But then the other part of the movie that blew my mind was that, in every way shape or form, Burt Reynolds is set up to be the hero in the first 45 minutes, and he does fit that function during that encounter. But then shortly thereafter he's fucked up and that's it [claps hands together]. He's completely useless.

KM: And then it's all up to Jon Voight...

QT: It's all up to Jon Voight. That's still one of the best movies ever made about, for lack of a better word, masculinity.

KM: ... I can't really compare you to any director...

QT: But if you could, who would you compare to me to? In the last twenty years?

KM: I can't think of anyone contemporary. The one director I see a brotherhood with, though, is Robert Aldrich because he could do tight smaller picture like Kiss Me Deadly [1955] and then he'd do an epic, irreverent movie like The Dirty Dozen [1967]. Like Reservoir Dogs [1992] to your Basterds [2009]...

QT: Well, I'm a student of Aldrich.

KM: You need to do a woman's picture then! Like his Autumn Leaves [1956].

QT: The Killing of Sister George [1968] for me! [Laughs]

KM: What about the The Legend of Lylah Clare [1968]?

QT: Oh, I don't like that one! That's awful. Even I can't get through that one and I love Aldrich. I've tried! I keep trying! Every time it's on TCM I record it and I give it another attempt. [Laughs] But The Killing of Sister George I do love.

KM: When I saw the live read I thought about old confinement movies, like Felix Feist's The Threat [1949] -- the live read and the movie have also been compared to Ten Little Indians [1965] or The Petrified Forest [1936] which was originally a play, did those influence any of this?

QT: I didn't watch The Petrified Forest again and I didn't rewatch Key Largo [1948]. But, frankly, to tell you the truth, I did watch some B movies that could be considered plays. I watched Shack Out on 101 [1955], which plays like twisted Eugene O' Neil.

KM: These would make great stage plays. Why not remake some of these pictures at plays? Like Detour [1945] on stage?

QT: Absolutely they would make great stage plays. I watched a lot of the movies that would be terrific plays. For instance, one spaghetti western could be done on stage. It takes place at a weird middle ground between a place like Minnie's Haberdashery and the place where they all hang out at the beginning of Once Upon a Time in the West [1968]. It's called Shoot the Living and Pray for the Dead [1971] with Klaus Kinksi... Or something like The Outcast of Poker Flats... But then also, as we discussed, it was very much influenced by 60s TV westerns. I also watched a lot of the TV westerns that had a home invasion kind of vibe. There's a Virginian episode where Darren McGavin and David Carradine take over the Shiloh Ranch and hold everybody hostage... There was one line in that Virginian episode that was so fucking good. And there was no way I could have made [that line] work, but I wanted to. Darren McGavin shows up at the Shiloh Ranch, he ends up shooting a couple of people just to make his point, but one of them is the cook. And then he makes Betsy, Roberta Shore, make him some dinner. So he's at Lee J. Cobb's table and he's eating his food and he's talking shit, and then he finishes and he goes, "Wow. That meal was really unmemorable. Always remember: Don't shoot the cook." [Laughs] That's a great line!

There's much more to read, so check out the entire interview at Sight & Sound and buy the issue here.

Read more Kim Morgan at Sunset Gun.