American teachers may be getting smarter.

Still, scrutiny of their work and cries to overhaul the education system intensify.

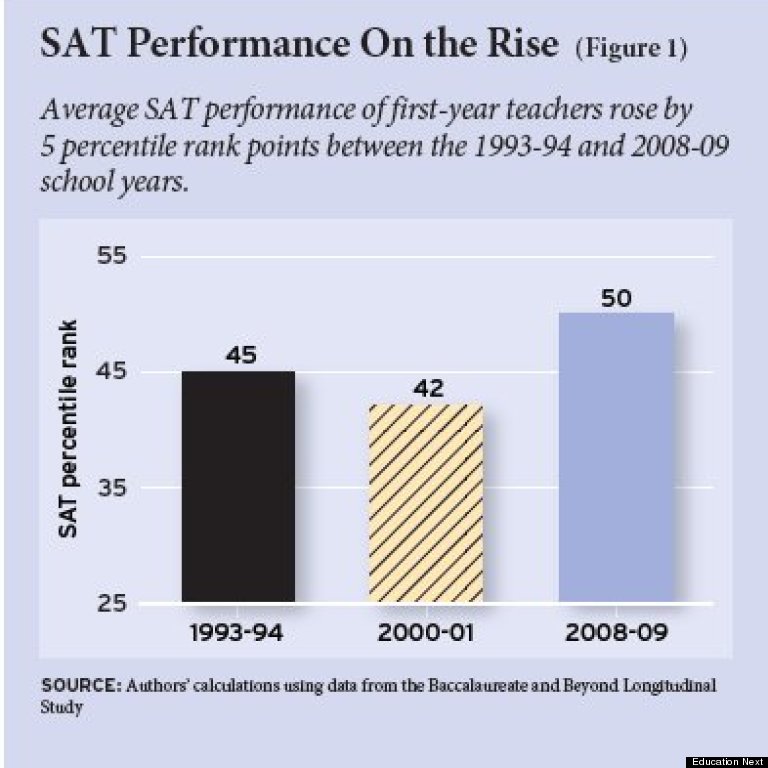

The education reform group National Council on Teacher Quality, and Harvard University's Education Next journal on Wednesday each released a paper about the state of the teaching force. The paper by National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington-based think tank that has long advocated for rigorous teacher evaluations, provides an overall look at how states are evaluating teachers and using the results. The Education Next paper, authored by the University of Washington's Dan Goldhaber and Joe Walch, investigated the academic qualifications of new teachers and found that average SAT scores have increased significantly over the last decade.

Taken together, the articles show an evolving workforce that raises questions about the often extreme hand-wringing over teacher quality. "Although teachers in the U.S. are more likely to be drawn from the lower end of the academic achievement distribution than are teachers in selected high-performing countries, the picture is a bit more nuanced than the rhetoric suggests," Goldhaber and Walch wrote.

Advocates who have supported the evaluations highlighted by National Council on Teacher Quality continue pushing states to take them further -- higher SAT scores or otherwise. "The SAT data is an encouraging sign, and we should keep heading in that direction, as it seems to be an indicator of whether a teacher can actually produce gains," said Eric Lerum, a vice president at StudentsFirst, the Sacramento-based lobbying and advocacy group started by former Washington schools chancellor Michelle Rhee. "But it doesn't tell us enough -- Goldhaber says it's not conclusive enough that the trend is reversing -- and we're still not taking enough top-shelf talent and getting them into teaching. We need to use the data we do have and take a comprehensive approach toward improving teacher quality."

Over the last few decades, in the wake of an alarming 1983 report about the state of American education known as "A Nation At Risk," policymakers sought to increase the accountability of schools and teachers to keep the U.S. competitive with international peers. This outcry came with concerns that increased career opportunities for women meant fewer teachers with stellar academic qualifications. Out of those fears came No Child Left Behind, the sweeping George W. Bush-era law that required regular standardized tests for students, and determined consequences based on those scores. At the time, some education experts speculated that these changes would dissuade would-be teachers from entering the classroom.

That theory, Goldhaber said, is likely false. "We didn't find any evidence that the smarter -- as measured by SAT scores -- teachers were shying away from NCLB subjects," he said. "There's a fair amount of concern, but not much evidence about high-stakes policies driving people out of teaching." (The paper, though, did not look at new teachers in the current era of revamped teacher evaluations -- a form of more individualized accountability and higher stakes.)

Goldhaber and Walch looked at teachers beginning their education careers from 2001 to 2008, and found that the average SAT scores of first-year teachers in 2008 was 8 percentile rank points higher than those of new teachers in 2001. That boost makes first-year teachers in 2008 more likely to come from the top-scoring half of SAT takers -- unlike their predecessors. (The paper, though, did not look at new teachers after 2008 -- so it doesn't account for people who started after the more rigorous evaluations took effect.)

"What may appear to be small changes … they don't look small to me," Goldhaber said.

It's unclear whether the shift is sustainable, or whether it was driven by the recession, which may have inspired job-seekers to settle for stable teacher jobs rather than riskier employment with higher pay.

Tim Daly, president of TNTP, a group that provides alternative certification for teachers, agreed that the shifts are meaningful. "More qualified people were more likely to enter teaching and less qualified teachers were less likely to enter teaching. It's not that there were just more vacancies," he said. "The significance for the quality of the workforce and student outcomes is less clear: SAT scores alone don't explain variation between teachers."

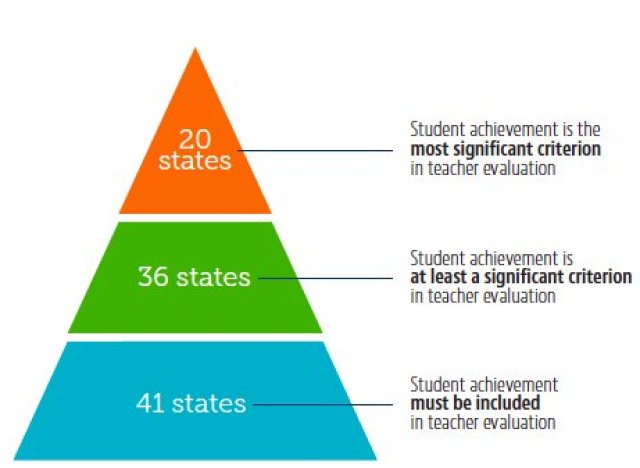

Meanwhile, teachers face tougher evaluations than ever, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality report. "The number of states that have moved so far forward on teacher evaluation is just striking -- more than 40 states now require student achievement to be a factor in teacher evaluations is very different from where we were before," Sandi Jacobs, the group's vice president, said in an interview. "There's been a real transformation."

As of September, 35 states and Washington, D.C., require schools to evaluate teachers based on student achievement -- in many cases, on standardized tests, according to the report. Forty-one states require the general use of student data in evaluations -- up from 15 states in 2009. Eight of these states use evaluations to determine licensure advancement.

National Council on Teacher Quality attributed the rapid pace of change to the Race to the Top, the federal government competition that had recession-addled states vie for money in exchange for implementing education reforms, such as teacher evaluations.

But states aren't moving quickly to link these evaluations to other areas that could improve teaching, Jacobs said. Districts are still using seniority, and not performance, to determine layoffs.

"Just measuring teachers is a first step, but what are you going to do with that data?" Jacobs asked. "In some places, states are moving on evaluation because they've been incented to do that through waivers and other mechanisms and aren't really thinking about what they're going to do with that data."

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers union, decried the findings.

“This report shows that teacher evaluation systems in 35 states and the District of Columbia are driven by tests, requiring that student achievement results be a significant, or even the most significant, factor in teacher evaluations," Weingarten said in a statement. "Yet only 20 states and the District of Columbia require that teacher evaluation results be used to inform and shape professional development for all teachers. We have to stop test-centric evaluations and build systems that will actually improve teaching and learning.”