Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is the wisdom indigenous and local people acquire by living on the earth. Rooted in a specific landscape and based on the fact that everything is connected, TEK braids together relationships between plants, animals, the earth, the seasons, and people. At its heart lies the concept that human and non-human components of the natural world are inseparable. Additionally, TEK links ecology to spirituality and cultural values.

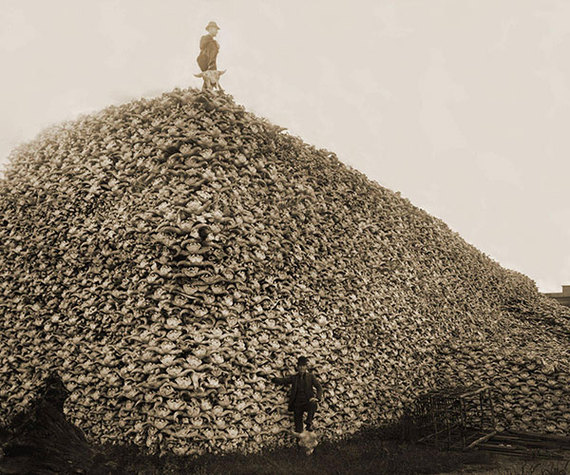

A TEK worldview contrasts sharply with the command-and-control approach to the natural world Euro-American settlers brought to North America in the 1600s. In response to the wave of extinction they caused, in the late 1800s US and Canadian leaders created the North American Model of wildlife and forest management. This model was forged by Theodore Roosevelt, who thought nature needed to be conserved by man for our benefit and use, and Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the US Forest Service, who saw natural resources, be they forests or deer, as crops to be produced and harvested sustainably.

Roosevelt's and Pinchot's well-intentioned ideas about natural resources created other problems that we're working to fix today. For example, they believed that anything that interfered with top-down management, such as wolves and fire, were inconveniences to be eliminated. Under a Pinchovian regime, they swiftly were.

In the middle of the last century we learned some hard lessons. Ecologists Charles Elton and Aldo Leopold discovered that wolves and fire have essential roles in keeping ecosystems healthy. Rachel Carson found that everything is connected and that how we managed rivers, croplands, and forests had created a lethally toxic wasteland. Consequently, we began to listen to Native Americans and First Nations who for thousands of years had inhabited this continent freely with millions of migratory bison and several hundred thousand wolves, and who set fires to invigorate prairies.

In 2006 as a new PhD student, I began working on a transboundary research project in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem in two national Parks: Glacier National Park in Montana, and Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta. I wanted to know how wolves interact with fire to influence aspen ecology. Six years later, when I completed my PhD, I'd learned that wolves need fire to control elk in this ecosystem.

Fire, which causes trees to topple and aspens and shrubs to sprout madly, gives wolves a hunting advantage. In this prairie-aspen landscape, elk chased by wolves hit fire sites and stumble over downed, fire-killed trees and new sprouts. Where there are wolves, to stay alive elk must avoid severely-burned places. This gives aspens and shrubs a break, enabling them to grow above the reach of hungry elk. Lacking wolves, complacent elk browse post-fire sprouts to death. Relationships in which an apex predator (such as the wolf) directly affects prey behavior and indirectly benefits plant communities are called trophic cascades.

Since 2008, thanks to Waterton natural resources officers and Parks Canada funding and logistical support, my colleagues and I have been studying two fires: the 2008 and 2015 Y-Camp Prescribed Fires, which burned 1,200 hectares twice, and the 2014 Red Rock Complex Prescribed Fire, which burned 2,300 hectares. These sites contain a very high elk density and two wolf packs. Managers' main objective is to restore the prairie in the burn units. To that end, we're investigating whether two key ecological forces historically present in this system (fire and wolves) without a third (bison) can return this fescue grassland to pre-Euro-American settlement conditions.

In 2013, Narcisse Blood, a leader in the Kainai First Nation (the Blood Tribe, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy), contacted me on facebook, curious about trophic cascades. Six months later, when the fireweed was in bloom and the elk were bugling, he and his wife Alvine Mountainhorse came to the Waterton research house for supper. Over homemade pizza topped with meat from an elk I'd hunted, we traded wolf stories for hours. Narcisse explained to me and my field crew that our study site lies at the feet of Chief Mountain, which is sacred to the Kainai. Alvine taught us the Kainai word for wolf: ómahkapi'si.

We stayed in touch across the wheel of the seasons. In 2014 and 2015, Kainai conservation biologist Kansie Fox, her natural resources technicians, and anthropologist Kurt Lanno joined us afield. We continued the conversation begun by Narcisse, who died tragically last year in a car accident.

As a result of walking this prairie together and exchanging ideas and stories, we've developed a partnership. With generous funding from the Kainai Board of Education, the AGL Foundation, Whitefish Community Foundation, Earthwatch Institute, and private donors, in summer 2016 we're initiating the Kainai First Nation Community Fellows Program. Kainai high school students, teachers, and community members will join us to learn to measure fire and wolf effects in this ecosystem. We'll share TEK and ecology as we discuss wolves and fire. We'll talk about the role of bison. And together we'll discover ways to honor this landscape and keep it as healthy, connected, and wild as possible.