On August 29 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans and then a nightmare unfolded. The most disadvantaged populations suffered the worst harm from the disaster. Many African American and poor individuals were unable to evacuate. Black neighborhoods were the most severely damaged. The elderly, blacks, and the poor were the most likely to die. And, after the disaster, the black and the poor evacuees were the least likely to be able to return to New Orleans. It was a particularly bad time to be elderly, black and poor in New Orleans.

Ten years later, the potential for a repeat of the disaster remains. The continuation of climate change means that the occurrences of strong hurricanes will increase. Hurricanes derive their strength from the temperature of the ocean. A two degree (F°) increase in water temperature more than doubles the number of Katrina-strength hurricanes occurring. Growing economic inequality and a weak economic recovery on Main Street has meant that the poverty rate, generally and among African Americans specifically, is higher today than it was in 2005. If we wish to mitigate the effects of future hurricanes and other disasters our emergency planning needs to better attend to the most disadvantaged among us.

Among the most universal household assets in the United States is a personal vehicle. However, automobile ownership reflects the race and class disparities in American society. Many faced difficulties evacuating New Orleans in 2005 because they lacked a vehicle and could not secure an alternative means of transportation out of the area.

Nearly a fifth of the poor population has no household vehicle compared to four percent of the middle-income population and two percent of the upper-income population. Even if middle-class and upper-class households do not have a car, they have the resources to obtain one in an emergency or an alternative means of transportation. Not all poor people can do the same.

Poor whites are more likely to own a vehicle than poor nonwhites. Nationally, 14 percent of the white poor do not have a vehicle in their household. The comparable figures for the Latino and black poor are 18 percent and 32 percent respectively.

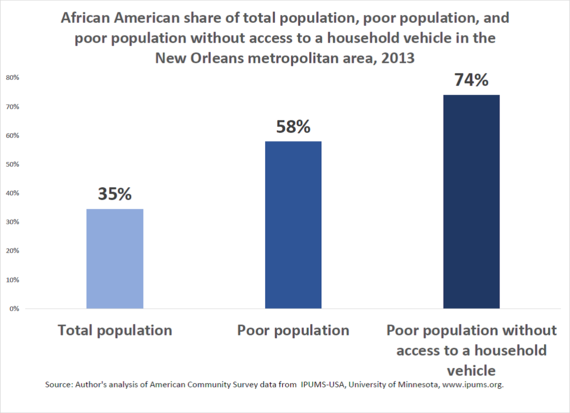

We can see evidence of this pattern in the New Orleans metropolitan area. In New Orleans, about half of the population is white, but only about three in ten of the poor is white. Of the poor population lacking access to a vehicle, only about a tenth is white. In other words, as the economic hardships increase the white share of the people facing the hardship decreases.

The reverse is true for African Americans. In New Orleans, blacks make up about a third of the metropolitan population, but nearly six in ten of the poor population. Three fourths of the poor population lacking access to a vehicle is black. As the hardships increase, the African American share of the people facing the hardship also increases. We see this pattern for African Americans not only in New Orleans but also in the other hurricane-prone metropolitan areas of Houston and Miami.

The lesson from Hurricane Katrina is that emergency planning needs to pay attention to the most disadvantaged groups. In emergencies, the poor, the nonwhite -- particularly African Americans, and the elderly will require extra attention and resources because they are the least likely to be able to help themselves survive a disaster.

American communities are highly segregated by race and ethnicity. There are also differences in groups' media choices and communication networks. In our segregated society, a universalistic approach to outreach and education about natural disasters will not be as effective as an approach that acknowledges American spatial and social divisions.

In the short-term, effective planning and targeted outreach can mitigate the effects of future disasters. In the longer-term, we need to significantly reduce race and class inequality, and to address climate change.