Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

On August 7, 1998, between 10:30 and 10:40 a.m. local time, suicide bombers parked trucks loaded with explosives outside the embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi, Kenya and almost simultaneously detonated them. In Nairobi, approximately 212 people were killed, and an estimated 4,000 wounded; in Dar es Salaam, the attack killed at least 11 and wounded 85. The attacks were later traced to Saudi exile Osama bin Laden and took place on the eighth anniversary of the deployment of U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia. Prudence Bushnell was Ambassador to Kenya at the time and relates the harrowing events of those days in an interview conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy for ADST in July 2005. Read the entire account on ADST.org

Prudence Bushnell was Ambassador to Kenya at the time and relates the harrowing events of those days in an interview conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy for ADST in July 2005. Read the entire account on ADST.org

BUSHNELL: In the '90s, President Clinton felt compelled to give the American people their peace dividend, while Congress thought that now that the Cold War was over there was no need for any significant funding of intelligence, foreign affairs or diplomacy. Needless to say, there was no money for security.

The security offset prescribed by the Inman Report in the aftermath of the truck bombing of our embassy in Beirut in the '80s, was non-existent. Three steps from the sidewalk and you were in the embassy. We may have had about 20 feet of offset from the rear parking lot, but no more. We had an underground parking lot, which was inadequate, and we were squatting on some space in the front, but that was it.The information [about al Qaeda] was highly compartmentalized, on a "need to know" basis and clearly Washington did not think the US ambassador needed to know. When the Kenyans finally broke up the cell in the spring of '98, I figured "that was that."

On Friday, August 7, we started another business day as usual. I was finally successful in scheduling a meeting with the Minister of Commerce to talk about an upcoming U.S. trade delegation. I remember asking that the Country Team discuss how our newcomers were settling in and whether we were reaching the right balance on issues of security alerting but not paralyzing people to the dangers. In retrospect, that was a very ironic conversation. The office of the Minister of Commerce was on the top floor of the Cooperative Bank building across from our small rear parking lot. As was the case in many official meetings, the Minister had invited the press to ask questions and take photos before the real talk began. A few minutes after they left, we heard a loud "boom."

The office of the Minister of Commerce was on the top floor of the Cooperative Bank building across from our small rear parking lot. As was the case in many official meetings, the Minister had invited the press to ask questions and take photos before the real talk began. A few minutes after they left, we heard a loud "boom."

I asked, "Is there construction going on"? It sounded like the kind of boom you get when a building is being torn down.

The Minister said, "No, there isn't." He and almost everybody else in the room got up to walk to the window.

I was the last person up and had taken a few steps when an incredible noise and huge percussion threw me off my feet. I'll never know whether I totally lost consciousness or whether I was semi-conscious, but I was very aware of the shaking of the building.

I thought the building was going to collapse, and I was pretty sure I was going to die. At the same time I was calmly thinking "this building is going to fall and I'm going to die." I vaguely remember a shadow, like a white cloud, moving past me and the rattle of the tea cup.

Then I looked up. With the exception of a body prone on the other side of the large office, I was the only person left in the room that had held about a dozen people before the explosion occurred. Almost simultaneously, the man I took for dead raised his head, and one of my Commerce colleagues returned.

I tend to be calm in emergencies and I was probably in shock and maybe denial because I didn't want to leave the floor until we made sure that everybody else was out. We met up with a couple of people including the elevator operator literally wringing his hands saying, "Sorry, I'm so sorry, oh sorry, sorry!" For some reason I thought the building had been bombed because of a nasty banker's strike that was taking place.

So, off we went, down an endless flight of stairs. At every landing we would have to climb over the steel fire doors that had been blown in. Debris, blood, shoes and pieces of clothing were scattered at every floor.

What I did not know was that around 10:32 a truck with 2,000 pounds of explosives drove into the small rear parking lot I had walked across earlier. The lot was squeezed between the embassy, the Cooperative Bank Building and a seven-story general office building.

The truck drew up to the guarded entrance to the underground parking lot of the embassy. One of the two occupants got out and demanded entry. The guard refused and tried to alert the marines via radio. The perpetrator then hurled a stun grenade (the noise we and thousands of other people first heard), then ran. Seconds later, his companion detonated the explosives. The two tons of energy hit the three buildings surrounding the parking lot and bounced off and over the bricks and mortar with devastating effect. Two hundred thirty people were killed instantaneously. Over 5,000 people were injured, most of them from the chest up and most of them from flying glass. Vehicles and their occupants waiting for the corner traffic light to change to green were incinerated, including all passengers on a city bus. The seven-story office building next to the embassy collapsed and the rear of our chancery blew off. While the rest of the exterior of our building had been constructed to earthquake standards, the windows shattered, the ceilings fell and most of the interior simply blew up.

Two hundred thirty people were killed instantaneously. Over 5,000 people were injured, most of them from the chest up and most of them from flying glass. Vehicles and their occupants waiting for the corner traffic light to change to green were incinerated, including all passengers on a city bus. The seven-story office building next to the embassy collapsed and the rear of our chancery blew off. While the rest of the exterior of our building had been constructed to earthquake standards, the windows shattered, the ceilings fell and most of the interior simply blew up.

Forty-six people died -- about a quarter of the occupants -- while others were struck or buried by rubble. All of the cars in the parking lot caught fire, which spread to the top of our generator. On the opposite side of the building, all of the windows blew in. In my office, the Country Team ducked as the windows blew, then crawled downstairs and exited the building along with everyone else who was still able.

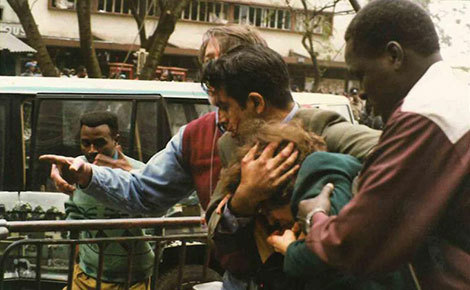

The two front office managers began to record the names of people as cars still fit to drive were flagged down and the injured sent to hospital. Thousands of people were drawn to the scene, many of them crawling over the rubble of the collapsed seven-story office building to try to save those who were buried.

All I kept thinking was that I just needed to get out of there, to get to the Medical Unit and we would be okay. At one point, the slow parade of people came to a standstill. Some people yelled, "Hurry up, move; there's a fire"! As smoke wafted up the stairwell, I thought for the second time that I was going to die. Again, it was a peaceful thought because at least I'd be asphyxiated and not burned to death.

Because I was looking down, my first sight of the bomb's impact were shards of glass, twisted steel and, all of a sudden, the charred remains of what was once a human being. That's was caused me to look up. What I saw was fire (hence the smoke in the stairwell), rubble, destruction and the remains of what had been the rear wall of the chancery. A few steps further and we met the acting DCM coming around the corner. He looked at me very calmly and said, "Hello Ambassador." What I didn't know was that, having organized and helped the team that returned to the building to help the buried, dead and wounded, he was now searching for his wife, like us, in shock....

The information about what had happened and how people were doing came in waves. It got worse and worse as time went on. I mentally kept track of the people I saw or heard from and those I didn't.

I learned that our Marines had been sitting in their van outside the embassy waiting for one of their colleagues to cash a check when the bomb went off. The one who went in to get the money was killed. Another fell down the elevator shaft but returned with broken ribs from the hospital to help in the rescue. I learned about the janitor who put his life at risk to turn off the generator before the water hit our electrical wires. I learned about acts of incredible courage and terrible deaths.

As the day went on, the nightmare grew. Too many dead, too many wounded. Hospitals were flooded with thousands of walking wounded, most bleeding terribly from wounds to chest and face. I returned to our operations' center at AID as soon as I could. Can't remember everything we did but I know I was incredibly grateful for the fact that we had a large mission with lots of willing hands and a senior team that was alive and experienced enough to take over when necessary. I was also thankful for the experience of having handled disasters before so I could provide the kind of instructions that would hopefully help save lives. About ten that night, I left the ops center in the good hands of AID and embassy officers who could cope and went home exhausted. I was too tired to even wash off the clots of blood stuck in my hair. It had been a horrible night.  Downtown, people had worked all night to dig survivors out of the collapsed office building. At our operations center, the night shift had been relaying information to the Washington task force and keeping tallies of our dead, wounded and missing.

Downtown, people had worked all night to dig survivors out of the collapsed office building. At our operations center, the night shift had been relaying information to the Washington task force and keeping tallies of our dead, wounded and missing.

I needed to see the embassy so I went there first in the morning. Reinforcements for the Marines providing perimeter security had still not arrived but everything was calm. Our Security Engineer had established a lean-to office on the sidewalk and escorted me through the remains of our building. The devastation inside had a deathly stillness to it. I laid roses sent to me by the Permanent Secretary of the Foreign Ministry, on the steps leading into the building because it had now become a sacred place...

American members of the community had gone to sit with those waiting for news of the whereabouts of loved ones, or reeling from information of the death toll. I visited a couple of them that day. Sue Bartley, spouse of our Consul General, Julian Bartley, was already aware that her son had been killed and was holding out the hope that Julian would be found alive. Julian, like other of our African American colleagues, had been mistaken for Kenyan and taken to one of the many over-crowded morgues around the city.

The U.S. military had sent a number of doctors and counselors to help the Kenyans, because the Kenyan medical establishment was overwhelmed.

The Department at this time had very little experience with the kind of situation Nairobi and Dar were in. We're very good at evacuating people and we're good at taking out our dead. But a terrorist attack that leaves some dead and some not was something we had much less experience with. I pulled everyone into our operations center and laid down the law.

I told everyone to "Take a good look at me. I am the Chief of Mission. This is my mission and nothing happens unless I say it happens. Here is the Acting DCM. If I'm not here, he's the one who says what's going to happen." We then organized the visitors so that rather than meeting with all these little groups separately, they would coordinate among themselves, and I would meet with a couple of them every morning or twice a day.

Sunday we held a memorial service for the Americans and dealt with the international news media. Of course they wanted a press conference. I did not want any photographs taken, because I looked pretty banged up but was persuaded otherwise.

I smile, because about a week later my OMS came up to me and said, "You know, Pru, I really shouldn't be saying this, but I've been seeing pictures of you on television and in the newspaper and I have to say it's good that you got your hair done a few days before we were bombed. As bad as you looked, your hair was okay." When Secretary Albright came I had two conditions: that we not have to prepare briefing papers, because we had lost all of our computers, and we had nothing. And the other, that she not spend the night, because the security involved in that would have been so astronomical. As it turned out, the plane had problems in Dar, and she had to cut her trip short.

When Secretary Albright came I had two conditions: that we not have to prepare briefing papers, because we had lost all of our computers, and we had nothing. And the other, that she not spend the night, because the security involved in that would have been so astronomical. As it turned out, the plane had problems in Dar, and she had to cut her trip short.

Rather than meet with the opposition political figures one by one, we invited them to a wreath-laying at the site of the embassy and the building that had collapsed. They were further outraged. I, in turn, became almost as angry with them.

I was so mad at them that I refused to see them until Christmas. The Country Team advised me to contact them earlier but I had decided to hell with being ambassador. These politicians were human beings to whom I had paid respect and support who chose to make a spectacle of circumstances for no reason but political show.

The Department returned to business as usual much faster than we were ready and we felt that there was a lack of understanding as to just how blown away we literally had been.

People would start saying, "Well, you didn't respond to our cable, what's wrong with you"?

"Well, our communication system had been blown up." For a while I was interacting with the Department via Hotmail.

Once the Secretary and her entourage came and left, we received what I began to call the "disaster tourists." Well-meaning people from various parts of Washington who couldn't do a thing to help us.

In November I sent a cable to Washington requesting by name the people we wanted to visit. They didn't seem to understand the difference between those VIPs who could be part of the solution and those having their photographs taken in the remains of the embassy...

The grounds had been leased to us by the Kenyan government for 99 years and we still had lots of time left. People voiced concern that if we returned the land, one of the land-grabbing members of Moi's cabinet would seize it to construct heaven knows what. I went back to FBO [Foreign Buildings Operation] requesting that we construct a memorial park and began another round of mutually irritating conversations -- "We don't do memorials!" My instructions were precise: hand it back. We did, but not before I cornered every senior member of Moi's government with the request that he support the establishment of a memorial park.

My instructions were precise: hand it back. We did, but not before I cornered every senior member of Moi's government with the request that he support the establishment of a memorial park.

The local American business organization had offered to landscape it and provide money for upkeep. I took a cue from the Vietnam Memorial in Washington and asked that a wall be constructed with the names of everyone who had died in the attack so that their children and grandchildren could come and remember them.