Mexico is in a political crisis again. The sudden announcement of a 15-20% hike in gasoline prices has triggered protests, blockades and general social unrest at a scale not seen since late 2014 when the president, Enrique Peña Nieto, was saddled by the back to back blows of the Ayotzinapa kidnappings and "Casa Blanca" scandal. That it happens at the beginning of what is shaping up to be an extremely complicated year is even more troubling. Already the economy is showing signs of a deepening slowdown and inflation is creeping up. Most worryingly, however, is that the fallout from Trump's electoral victory is starting to be felt even before he has taken office, as evidenced by the decision of US carmaker Ford to cancel a $1.6 billion investment in Mexico. Be it by threats or fiscal incentives, it is likely that more will follow.

Popular opposition to the gasoline price hike partly obeys personal economic logic. Mexico is an extremely car-dependant society and given low wages, the cost of gasoline is an important component of the consumer goods basket. Gasoline prices in Mexico have traditionally been regulated by the government and until 2015, were gradually raised on a monthly basis (known colloquially as the gasolinazos) through the Impuesto Especial sobre Productos y Servicios (IEPS) a "special" tax on certain goods including fuel. However, liberalization of gasoline prices was one of the pillars of the vaunted energy reform in order to align domestic prices with global ones. Peña Nieto himself in 2015 promised that there would be no more gasolinazos thanks to the energy reform, a promise that has now been widely mocked on social media. That consumers will face not only this price hike but the natural rise in market prices from February onward (which will possibly mean a liter of gas 30% more expensive by year end), plus the inevitable inflation that will follow adds insult to injury.

Cheap gasoline or cheap tax income?

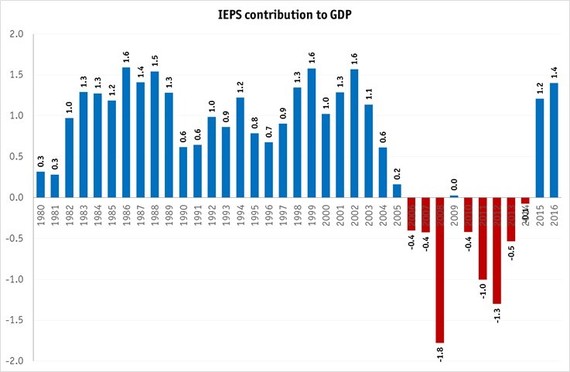

The IEPS was originally established in 1980 as a package of sin taxes set on cigarettes, alcohol, gambling among others, and most recently expanded to include junk food. Gasoline and diesel was also included, both as a sort of Pigovian tax (to compensate the negative externalities of excessive vehicle use) as well as a price smoothing mechanism. Conceivably, when oil prices would spike the IEPS on fuel would automatically transform into a subsidy but it would take a quarter century before prices rose to a level where this was the case: it was only in 2006 when intake from the IEPS on fuel would be negative, that is, when it became a subsidy. The subsidy was biggest in 2008 when oil prices reached record highs: it accounted for around 1.8% of GDP, quite an astronomical amount considering total non-oil tax intake that year was a paltry 8.1% of GDP. It remained negative (aside from a brief and minuscule return to surplus in 2009) until 2014 when oil prices once against slumped. By 2015 it was a tax again, bringing in 1.2% of GDP. Just in the first ten months of 2016, the IEPS has brought in 1.4%.

Critics of the government's policy of regulated gasoline and diesel prices due to the wasteful (and regressive) subsidy that has resulted over the past decade has forgotten that throughout most of the IEPS's life, it was not a subsidy; it was a tax. And that as a price smoothing mechanism it performed exactly as it was supposed to, helping Mexican consumers pay below-market prices to compensate paying above-market prices while oil prices were low. Throughout the whole of its 36 year existence, the IEPS has provided a net 23.3% of GDP to the public coffers, equivalent to nearly three years of tax intake - quite a significant amount. The government's claim that Mexican consumers have been spoiled by low gasoline prices when in fact it has been the main beneficiary of the IEPS is disingenuous.

Mexican gasoline is not competitive

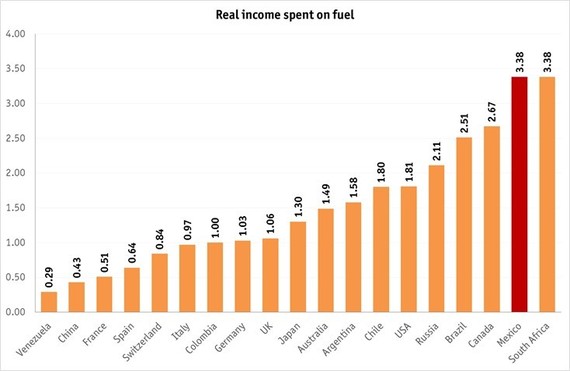

One of the government's recurrent arguments against the IEPS, as a subsidy, has been that Mexican gasoline prices are low by global averages. While Mexican prices are noticeably higher than the US as well as most other major oil producers, it is well below European prices as well as that of most non-oil producers. Even with the latest price hike into account, Mexicans pay 84 cents per liter, below the global average of around a dollar. Finance minister José Antonio Meade in his defense of the price hike claimed that Mexican prices were still "among the most competitive" on this basis. But contrary to his claim, Mexicans do pay considerably more when adjusting for income. According to Bloomberg, fuel costs amount to nearly 3.4% of the average Mexican's real income, almost double that of the average American and over four times that of the average Swiss. It tied with South Africa for the highest share among the 60 countries surveyed. As for actually being competitive, there's a reason nearly 70% of Mexican gasoline is imported from the US, given the country's modest refining capacity (less than a tenth of the US) and inefficient distribution network.

Are Mexicans to blame for being so gasoline dependent? Car usage is certainly an aspirational phenomenon not just in Mexico but among most developing economies. However, urbanization is arguably the single most important factor influencing car usage here; Mexican cities are simply not designed for mass transit. Even Mexico City, the city with the most developed public transport network in the country, the extensive Metro system does not have a single stop in many of the city's dispersed business districts and accessing some like Santa Fé (Mexico City's version of Canary Wharf in London or La Defense in Paris) is all but impossible without a car. The Metrobus, a rapid bus system, has helped plug some gaps but neglect of the normal bus network means that it suffers from overcrowding. Indeed the normal bus network cannot be described in any other term than woeful. It is composed primarily of microbuses, operated as individual concessions with no central authority. Most of the microbuses are in an appalling state and suffer from frequent mass muggings, with the routes outside the city limits in the Estado de Mexico particularly dangerous. With this in mind, can anyone blame the middle and upper classes (and a good part of the working class too) for what they can to avoid public transportation?

Was there really no alternative?

In a press conference defending the move, Peña Nieto claimed that the gasoline price hike was the only alternative to raise resources; the only other option would have been to reduce social spending. Governments frequently need to make difficult and unpopular decisions, particularly when it comes to taxation. But the macroeconomic imperative to enact such a move appears puzzling, particularly at the beginning of such a critical year and with public approval of the government at rock bottom.

Mexico is not facing a budgetary crisis, at least according to the government's own fiscal estimates. Tax revenue has consistently overshot estimates since the fiscal reform was implemented in 2014, oil prices are forecast to rise slightly, and the economy is not in recessionary territory even though nobody expects 2017 will be a bountiful year even by the current administration's underwhelming track record. It follows that either the government grossly underestimated the social discontent that a gasoline price hike could have had and therefore assumed it would be an easy way to raise extra cash without incurring debt; or it genuinely fears a major shortfall in 2017. If the latter case is true, then the government was prepared to assume the political cost of such a policy even when there's a key election later in the year (in the PRI bastion of the Estado de México, Mexico's most populated state) and even when the man announcing the policy, finance minister José Antonio Meade, is a possible presidential hopeful for 2018. The implicit assumption of this scenario is also that the government believes the economy is much weaker than it's ready to admit.

Between the two scenarios, the first is the most likely one. And the key factor is debt. The Peña Nieto administration has had a disappointing fiscal track record, consistently running up deficits of over 3%, and swelling the debt stock to over 50% of GDP, having inherited it at less than 38%. This rise in the debt stock has also consistently overshot estimates: every single budgetary fiscal forecast since Peña Nieto took office has assumed that the following year would be the last before debt levels would begin easing (and the 2017 budget is no exception). For a time, the government was able to brush off criticism of its debt policy through the promise of the structural reforms. But with the economic slowdown now in its fourth year, and its fiscal credibility showing cracks, the government likely fears the game is up. Few economists will believe fiscal consolidation is a realistic prospect unless there is a cushion of extra revenue to finance this year's budget (which envisages eliminating the primary deficit) without significantly raising the debt stock.

The gasolinazo therefore appears to be a last resort to avoid that which the government most fears: a credit ratings downgrade. It should count itself lucky that one has not taken place yet; both Moody's and Standard & Poor's put Mexico on negative watch in 2016. At the EIU we've long believed that Mexico's fiscal and macroeconomic fundamentals do not support its current credit rating (The Economist Intelligence Unit's country risk service downgraded Mexico as early as 2015), nor did they justify the country's upgrade by all three major agencies back in 2013-14 as a result of the euphoria over the structural reforms. A downgrade is long overdue. Given the administration's hyper-sensitivity to negative foreign perceptions (particularly form investors), one can only imagine the panic in the halls of Los Pinos that will ensue when the downgrade comes.

The impact on 2018

Could Mexico have obtained these revenues in any other way? Perhaps not. Another year of austerity could have been an option but again, electoral considerations could be coming into play and the PRI may not be willing to shut the tap on spending. But the decision to risk such an unpopular move as well as a refusal to back down even when realizing the scale of public objection is telling of the lack of sensitivity - if not outright contempt - that this administration has had on public opinion under the belief that eventually, all political crises in Mexico fizzle out (as was the case back in 2014). Indeed the PRI went on to have a strong showing in the 2015 mid-terms which goes to show that arriving unelectable to the 2018 presidential election is not a foregone conclusion post-gasolinazo. But with the economy looking weaker and Trump now also in the equation, the odds of another six years in power are increasingly remote. The thought on Peña Nieto's mind will be whether defending a credit rating was worth it.

Follow the author on Twitter @raguileramx