Even metros with the most resilient of economies couldn't salvage many of their historic buildings downtown during the 1970s, the virtually undisputed nadir of urban America. It wasn't just a lack of investment--there simply was no psychological interest. In hindsight, we can ponder on the decade: it must have been an awful time to live in a city, and while most people at the time acknowledged that urban America wasn't looking so hot, it was impossible to say back then, without any context, if it really was as bad as it could get. And suburban living still seemed fresh, verdant, and sane. We held no hope for those old brick warehouses from the 1870s. Sturdy as they are, majority opinion a century later was that they were a waste of space.

The same could be said for the commercial and office buildings from the same era. By the 1970s, anything without adjacent dedicated off-street parking seemed like an anachronism, incapable of a renaissance. So, far too often, against the protests of a barely-organized historic preservation movement, the City chose demolition. In its place? Often little more than asphalt parking lots or the multi-story parking garages, endowing motorists from the suburbs with abundant parking.

Amidst this ethos, toxic as it may have been toward the built environment that made downtowns so central and so pivotal, usually a handful of great 19th century buildings remain. In smaller cities, the surviving fabric may comprise no more than a few blocks. Those few blocks, however, can define a place, like Grand Rapids, whose downtown generally enjoys accolades from visitors for its well-preserved buildings and active streetscape.

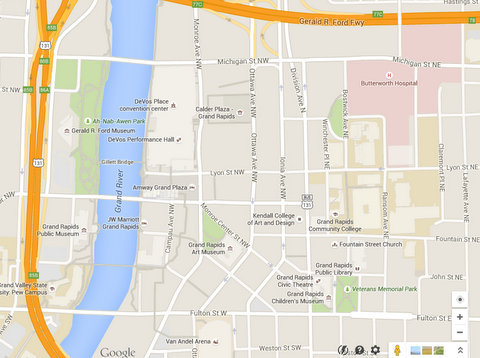

This Google Map roughly frames downtown. But the pulsing heart of the city--the area with the highest volume of pedestrian activity and active storefronts--is that triangular district where the street grid splays out at a 45-degree angle from everything else. A block or two south of Fulton Street displays some energy, but it tapers quickly. And north of Lyon Street is pretty inactive after 5pm. But a few blocks of contiguous activity is all it takes to shape the character of a downtown, and, since that triumphant triangle is more than most similarly-sized cities in the Midwest can claim, Grand Rapids justifiably earns the reputation of having a healthy, flourishing downtown.

And the Ledyard Building stands proudly as a centerpiece.

This view, at the intersection of Ottawa Avenue and Monroe Center Street, provides the best vantage for demonstrating the "flatiron" massing that, no matter how frequently it imitates its Manhattan progenitor, consistently manages to arrest the eye. But the building's footprint is much more than the wedge most commonly associated with this beloved architectural gesture.

In fact, most local references to the area use the term "Ledyard block", even though it evidently only comprises half of the triangle formed by the intersection of the two grids, as seen in the purple outline from the above map. Although the Ledyard Building does not comprise its entire block, it feels like it does. Notice how strongly the taupe asserts itself against its own cornice line.

The building's majestic scale only becomes obvious when viewed along Ottawa Avenue--the most expansive façade.

But all is not necessarily what it seems; the textures clash. The brackets differ along the cornices, window lintels vary greatly (as does the shape of the glass), and the façade colors change multiple times. It's almost like they're different buildings. And then there's that main entrance.

The attractive doorway supports three more stories of glass panes that serve as a mini-atrium. From the exterior, the glass fills a chasm in the street wall, creating continuity to the massing that otherwise wouldn't be there.

But why do this? By now, it should be obvious: the Ledyard block is several buildings, which, through subtle additions like the atrium on Ottawa Street, have fused into one sprawling complex. Little on the Ledyard is available online, but the current owners of the property, CWD Real Estate Investment, have provided a brief history through a capsule slide show. According to this presentation, it's the second oldest surviving building in Grand Rapids, founded in 1874 by William Ledyard, a prominent banker. It became home to the central public library shortly thereafter, but it had fallen into disrepair by the turn of the century, necessitating renovations in 1919--renovations that modernized the building to the standards of the time, when downtowns were still central to urban commerce. But by the early 1980s, it didn't matter what shape the Ledyard Building was in--downtown Grand Rapids was failing, like virtually every downtown in America. CWD Real Estate reports what may have saved the structure: further renovations in the 1980s involved the consolidation of "seven formerly separate buildings", giving rise to what people know today...the Ledyard Block.

The aerial photo above, from CWD Real Estate's presentation, reveals the sutures among the paved roofs. Apparently, the most ornamental of the façades on this block is the originally named Ledyard building, indicated by structure to the right of the glass atrium entrance in my two photos above and further reaffirmed by this link, courtesy of CWD. The rest? Part of the reconstructive surgery necessary in the 1980s, to keep the Ledyard block from turning into yet another parking lot. I can only speculate on exactly what necessitated the consolidation of all these individual structures into one contiguous campus, but my suspicion is that the smaller structures on this block were among the most vulnerable. In the 1980s, competitive businesses needed space to grow, not only with contemporary interior amenities--like central air and restrooms on every floor--but abstract qualities, such as modern standards for accessibility (i.e., convenient, cheap parking) and safety (securable entrances in a low-crime district). Most 19th century structures simply couldn't align themselves with late 20th century business practices without monumental physical changes. Though I have not discovered the various private/public alliances that morphed the Ledyard Building into the Ledyard Block, I suspect that, whatever aesthetic compromises took place, the result we see today is far better for Grand Rapids' downtown than any alternatives.

The Ledyard Building entered the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. I'm uncertain whether the consolidations and alterations would fit the more stringent standards of the National Register today, but, for the sake of Grand Rapids, it probably doesn't matter. A cluster of the city's most iconic buildings avoided implosion--their fate in so many other places. The timing was right for the Ledyard block. Hearsay indicates that, unlike most Midwestern cities, downtown Grand Rapids didn't reach its trough until the late 1970s, when the local furniture industry collapsed. If this is true, it may explain why the Ledyard Block survives today, since, by the 1980s, the first whispers of revitalization through preservation had begun to resonate across the country, after a handful of successes amidst the rampant demolition in the 1970s. Civic leaders in Grand Rapids could have passed resolutions with better urban intelligence in 1982 than they would in 1972. Regardless, all eight buildings in the Ledyard "Block" stand as a tribute to a city that, by most visual evidence, has a leg up on its peers not just in preserving its architectural history, but in cultivating a renewed little center to its metro of one million persons...and growing.

This article originally appeared in the author's personal blog, American Dirt. All photos taken by the author.