The Legacy of Democracy in Latin America

Latin America's experience with democracy is instructive in deciphering whether democracy has a real chance at succeeding and meeting the expectations of the citizens of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Fifteen years after Latin America was democratized, attitudes toward the benefits of democracy in the region have remained largely static. The 2011 Latinobarometro survey of people in 18 Latin American countries shows just 44% of respondents say they are satisfied with what democracy has brought to the region, with 52% of respondents saying they were actually dissatisfied with the results of democracy between 1995 and 2010.

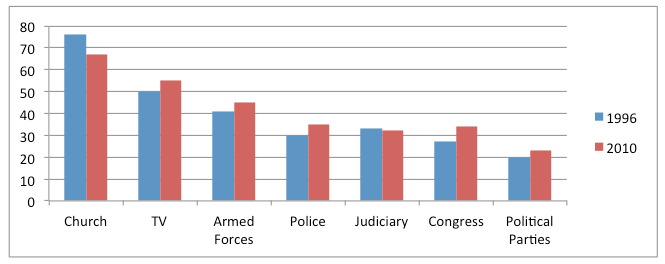

Comparing the results of Latinobarometro's results in 1996 versus 2010 on a range of topics, it turns out that more Latin Americans trust the church and what they hear on television than any political institutions. Trust in the church and the judiciary actually declined for the period (to 67% and 55%, respectively), while all the sources of authority and political institutions scored in the 40s and below. Just 39% of respondents felt that the region had progressed economically during the period, only 17% felt good about their current economic situation, 21% felt income distribution was fair, and a mere 26% expressed strong interest in politics.

Trust in Institutions in Latin America: 1996-2010 (%)

Source: Latinobarometro

So fifteen years of democracy has brought widely perceived economic stagnation, poor income distribution, distrust of political institutions and widespread political apathy to Latin America. Democracy in Latin America has produced Rousseff in Brazil, but it has also produced Ortega in Nicaragua and Chavez in Venezuela. If the deliverance of democracy has failed in the public's view in a region of the world that is largely homogenous in terms of language, religion, culture and history, what are democracy's prospects in MENA - assuming western-style democracy actually takes root there? (For the record, I think there is very little chance that will occur).

The Aspirations of Youth

Young people in the Arab world look at Latin America today and think that if democracy can be achieved on a continent with a decades-long history of authoritarianism and military rule, it should be possible to do the same in MENA. Indeed, according to the Burson Marsteller 2011 Arab Youth Survey, 92 percent of Arab youth aged between 18 and 24 now consider living in a democratic country their top priority - up from 50 percent in 2008.[1] However, as is the case in so many other parts of the world, the rising cost of living and concerns about unemployment are their greatest concerns. More than half the respondents characterized themselves as having a 'liberal' political orientation, and noted increased frustration with the domestic status quo throughout the region.

Can the 20-something generation's demand for genuine democratic rule be achieved in MENA, given the multitude of challenges and setbacks the region continues to experience? Arab Youth are likely to become increasingly disenfranchised and exasperated with time, as the ability and willingness of the governments that have replaced - or will in future replace - the previous regimes will likely prove to be incapable of satisfying their expectations. An Islamic government has already replaced the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia. The military-led replacement of Hosni Mubarak has displayed growing signs of intolerance and a propensity to prolong their time in power. And in Libya, all signs are that a hard-line Islamic government will replace the Gaddhafi regime.

There will inevitably be immense pressure on whatever form of government ultimately succeeds the current regimes throughout the region. They must be seen to be bringing about meaningful change quickly. This will be far more difficult to achieve than would ordinarily be the case, and is likely to result in one of two scenarios. The first is that, frustrated by the slow pace of democratic change and frustrated at the lack of visible and rapid improvements in the economy, protestors are likely to return to the streets, prolonging the economic chaos and adding pressure to the recovery process while at the same time increasing instability and insecurity. This has already been seen in Egypt.

Second, wary of falling prey to the type of mass protests the new governments helped to foment, and falling into the trap of trying to be all things to all of their people, the new governments have rushed through popular measures such as rises in the minimum wage and public sector wages - measures that they are not able to afford - that are sowing the seeds of even longer-term economic distress and postponing much needed genuine reform until some point in the future. Given this, as sad as it is to have to say, there appears to be very little chance that a western-style democracy that performs on a sustainable basis will ultimately emerge in any of the Spring countries. In the long-run, many of the citizens of these countries -perhaps most of them - are likely to yearn for the stability and predictability they had known for decades under the rule of a strong man. Life is likely to get much more difficult to the average person in the near-term.

Egypt as a Test Case

Earlier this year, in the first post-Spring polling of Egyptian opinion[2], there was greater fear among moderates over the possible rise of Islamists and greater sectarian violence. Egypt is a conservative country but a significant percentage of Eqyptians do not want the kind of Islamic rule prevalent in Iran or Saudi Arabia. Yet the Muslim Brotherhood is the best known and organized political force in the country and is poised to do well in next year's elections (if they occur as currently planned).

Numerous violent religious clashes have erupted between political and religious sects since Mubarak's departure. Although there is now a timetable for a democratic transition, it is difficult to identify anyone who speaks with authority that has genuine confidence that the transition to the Egyptian version of democracy will go smoothly, or proceed as originally envisioned. Economic hardship resulting from Mubarak's ouster has contributed to a climate of fear and uncertainty, and the military junta that took Mubarak's place has become increasingly intolerant.

In Egypt, female protestors have grave reservations over where the 'revolution' is heading. Female activists expected the revolution to yield greater liberty, equality and social justice for women. However, leading activists have expressed their disappointment at the way women are being sidelined[3] by the military government. Some fear an even worse outcome - that a rise in Islamist political parties will force women back into a subservient role. This would be a worst case scenario, and remains a remote possibility at the present time, but debate is flourishing in Egypt and no one can predict what sort of consensus or conclusions will emerge.

One consequence of the uprising and subsequent departure of Mubarak has been a rise[4] in sectarian conflict in Egypt, with several deadly clashes between Muslims and Coptic Christians erupting in Cairo over the past few months. Supporters of the Mubarak regime point to this as evidence of the stabilizing role the Mubarak regime played in Egypt, where such clashes were rare. Critics argue that members of the National Democratic Party (of which Mubarak was previously head) are trying to foment[5] sectarian strife in order to emphasize the former argument. However, human rights groups[6] have long blamed the Mubarak regime for failure to protect Egypt's Christian minority (approximately 10% of the population), impunity for perpetrators of religious-based violence, and its inability or unwillingness to promote religious freedom and tolerance among different groups.

The Rise of Unemployment and Poverty

In spite of these problems, polling[7] reveals Egypt's citizens remain cautiously hopeful, the majority are happy Mubarak is gone, and most are less likely to seek opportunities abroad. Egyptians express high support for democracy and civil liberties, but are actually more concerned[8] with the immediate struggles of finding jobs, improving security and feeding their families. Unemployment predictably rose across the region as the unrest persisted, and has stayed higher. The problem of unemployment also disproportionately affects certain sectors as well as the young. In Yemen for example, one million workers[9] in the construction sector are thought to have lost their jobs since the uprising began. The incidence of poverty in the region is also unlikely to change in anything but the medium- to-long-term as cash-strapped transitional governments (such as Egypt and Tunisia) and embattled regimes suffer from rapidly deteriorating public finances.

Some inadvertent effects of the revolution have hit the poorest the hardest. In Egypt for example, food prices doubled[10] since the outbreak of unrest and youth unemployment runs around 30%. Approximately 47% of the population lives on less than $2 per day in Yemen. As intractable a problem in the Middle East as in many other regions of the world, poverty is likely to be a key factor in determining the agenda of new governments in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia. Secular-minded parties are likely to be all too aware of this, given the tendency towards Salafist extremism, particularly in Egypt, which tends to come more from impoverished rural areas than major conurbations. The Muslim Brotherhood also finds the majority of its support in the more rural, poor and conservative towns and villages than in the major cities of Egypt, where the state security apparatus has a far greater presence.

This is going to increase the risk of populist social spending should a secular party take control of the Egyptian government. However, given the strength and organization of the Muslim Brotherhood, it is more likely that some kind of fractious coalition government will emerge in Egypt and may well involve Islamists and secularists working side by side. Indeed, this scenario may actually work out to be worse for poor Egyptians because it is highly likely to delay decision making, and may make it more difficult for reform and change to take place as the different parties squabble over the means to an end.

What if Winter Had Simply Stayed?

The average citizen in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen may well have been better off without the Spring; they wouldn't have suffered the violent repression that ensued, economic chaos as entire economies have ground to a halt, and a less physically secure environment in which to live. The primary concerns of average citizens prior to the Spring have resurfaced, and are now foremost in the minds of the majority of Arab citizens. There is little reason to believe they will be addressed in any meaningful fashion in the near- or medium-term by governments that are themselves finding their footing and determining the right mix between reform and repression.

Getting the Spring economies back on track, and young people employed, is going to be the priority for new governments throughout the region. This is easier said than done however, as newly elected governments are under immense pressure to deliver results quickly. Under the weight of expectations, and restrictive influence of low or negative growth, instability and discontent will remain foremost on the Arab street for the medium-term as these countries grapple with failing economies and come to better understand what is implied by living in 'democracies'.

Now that the genie has been let out of its bottle, there is no turning back. It remains to be seen whether events to date prove to be watershed moments in MENA's political history or simply a transferral of autocratic power from one despotic political force to another, but it is far too soon to say with any degree of confidence. The Latin American democratic paradigm has proven to be diverse, even though the countries of Latin America are largely homogeneous. One has to wonder what the real prospects for success are among the heterogeneous countries of MENA. The region is clearly off to a rocky start, which is to be expected. However, any realist would have to say that there is a greater likelihood that those countries that experiment with democracy stand a good chance of looking more like Iran, than Turkey. Hard as it is to believe, western governments still cling to the mistaken belief that a one size fits all approach to democracy will work around the world.

*Daniel Wagner is CEO of Country Risk Solutions, a cross-border risk management consultancy, and author of the forthcoming book Managing Country Risk (Taylor and Francis, March 2012).