Dressed in his signature black tee-shirt, jeans, leather belt with silver grommets, black boots, and matching discrete hoop earrings, Marvin J. Taylor, Director of the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University looks very much like the quintessential downtown dweller. Someone who is at home walking the streets south of 14th Street, the cobblestones of Greenwich Village and SoHo and the black-top of the Lower East Side.

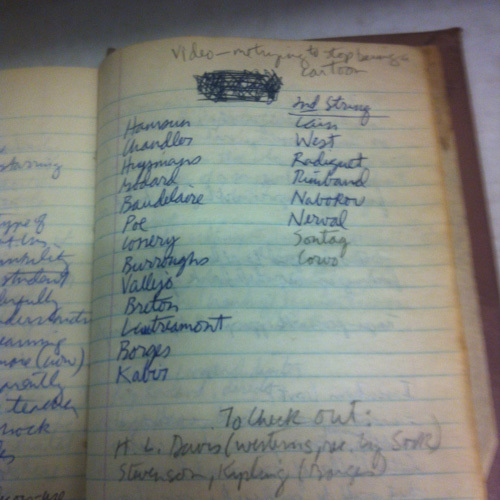

A native of Indiana, who first studied music (organ) at Indiana University in Bloomington and then switched to Comparative Literature and a Masters in Library Science, Taylor fell in with the punk band kids (many of them studio artists), long before he arrived in New York City. The first piece of downtown literature he read, given to him by his partner was Words in Reverse (1979) by Laurie Anderson, which presented texts from her performance pieces, where words, graphics, and minimal music merge in provocative non-linear ways.

By the time Taylor arrived at Fales in 1993, the library already had an Avant-Garde Collection of Beat and New York School poetry and a modest fiction collection of about 500 linear feet. Taylor's timing was perfect. It was a heady moment for the university which was in the process of remaking itself as new disciplines began to proliferate: area studies, and gender studies. It was also the heady days of queer theory.

Taylor thought about what he could do to make Fales and NYU unique and, spurred on by his ties to the activist community, one year later, in 1994, founded the Downtown Collection, which has now grown to 12,000 linear feet of archives, all but 3,000 of them already processed. The collection, which now includes vinyl, is so extensive that half of it is currently off-site, in a temperature and humidity controlled building in Putnam Country. A retrieval system is already in place.

Featured currently in the Fales Gallery space is Martha Wilson: Downtown, an exhibit drawn from Wilson's personal papers, one of 435 collections housed in the Downtown's comprehensive, controversial, and some might say, cantankerous archive. The gift of 80 boxes of material in 2007, Martha Wilson, said came quite naturally: "I felt like my experience as a downtown person should be preserved by Downtown."

Beyond their downtown identification, Wilson, an American feminist performance artist and the founding director of Franklin Furnace, said that she and Taylor shared the need, the urge to break out of the constraint of categories. In a journal entry by Wilson from the fall of 1998, she speaks of meeting Taylor: "Marvin and I come from the same point of view," Wilson wrote, adding that "Marvin is breaking down the divisions between libraries and museums. They both collect and catalog objects." Given their strong sense of history and community, both Wilson and Taylor were natural archivists.

For Wilson, who founded Franklin Furnace, a not-for-profit arts organization whose mission was to "present, preserve, interpret, proselytize and advocate on behalf of avant-garde art" in Tribeca in 1976, the breaking down of divisions resonated deeply. Wilson's artists were "doing pieces," not making art. The medium was to be appropriate to the idea. "If Christy Rupp wanted to make posters of rats and post them on a curb that was OK. The next project could have been made out of chicken bones," Wilson quipped.

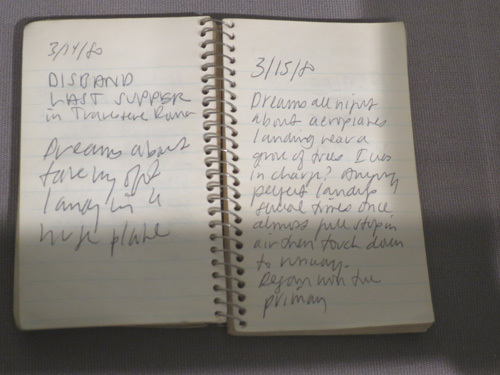

Official categories were for the convenience of the funders and the art historians who were looking at the downtown scene in a formal way. Wilson and Taylor both knew that the real situation was more fluid. Taylor once said that, "Everybody was in three bands." Wilson, however, was only in one, Disband, a group that made everything up as it went along and used strange props such as radios and rocking chairs.

To Wilson, the Downtown Collection was a "poifect fit!" Marvin Taylor not only shared her love and appreciation for the creative life of downtown New York City but he also came from a Quaker background, much like her own. "The Quakers never threw anything out," Wilson said. "The idea was to save a chair from generation to generation; to preserve something because it will mean different things to different people over time." This appealed strongly to Wilson who said that she was once criticized for saving ticket stubs.

To Taylor, his Quaker heritage added another dimension beyond thriftiness: living a life of self- reflection. It was a quality that Taylor saw immediately when he read Wilson's journal entries. "She was trying to figure out the way she was supposed to be as a woman in the 70s. It was difficult being a strong woman in the arts," he said.

Taylor first saw Martha Wilson's work at a small gallery in Chelsea where he fell in love with her early, gender-bending work. "Way before Cindy Sherman," he said, "Wilson realized that gender is performance identity is conceptual art." Taylor followed Wilson's career and, in the intervening years, they worked together on various boards and on the Artists Space Archives project now housed at Bard.

Always introspective, Wilson began to question things as they were. For one thing, there was the wisdom of having the largest collection in the United States of artist books made of paper housed in a loft constructed of wood. The decision was made in 1993 to sell the books to MoMA who asked for three copies of each work. MoMA kept the first copy (now stored in their Queens warehouse), sold the second copy to a book dealer, and returned the third copy (if any) to Franklin Furnace. Although the third set is incomplete, it is now housed in their Brooklyn office, leaving them with a "pretty respectable research collection."

For another, when Wilson turned 65, there was the question she asked herself: What will happen in 100 years? "It was lucky for me," Wilson said, "that so many Franklin Furnace alumni were on the Pratt Faculty. When Jennifer Miller went to speak to her dean, he loved the idea of our nesting at Pratt; he loved the idea of having a living and breathing arts institution inside the school."

Two years of negotiations ensued, with Franklin Furnace becoming an organization-in-residence at Pratt Institute in September 2014, with their moving their office and collections to Pratt in December, and with their official opening set for April 1st 2015. After so many moves, from its original home on Franklin Street in Tribeca, to John Street, to 80 Hanson Place (in the BAM arts cultural center), Wilson is relieved that Franklin Furnace has a new, permanent home at Pratt on Willoughby Avenue.

Wilson is clear about the future. "We remain independent organizations. The idea is that the students will have access to our artists and programs, and we will have access to their students and infrastructure." Although Pratt and Franklin Furnace recently applied jointly for funding to integrate their artist book collections electronically and physically--the ownership would not change.

Beyond their shift across the East River, however, Franklin Furnace has accomplished an even greater transformation in the virtual realm. With substantial grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, they have succeeded in publishing their events and records (slides, black and white photos, press releases, announcement cards and posters) online up through 1996. A third grant, for which they have already applied, will cover the decade 1996-2006. "Now people can see the Karen Finley presentation in their pajamas!" Wilson said.

Taylor is particularly pleased that, although Franklin Furnace's archive has found an institutional home at Pratt, both Wilson's personal papers (2007) and the Franklin Furnace Ephemera Collection (2008) are now in the Downtown Collection. The Ephemera Collection serves as an index, as a way of looking at the downtown scene internationally. Founded by Wilson's archivist Matthew Hogan, it consists of all of the flyers, press releases, and announcement cards sent to Franklin Furnace over the years from 149 institutions worldwide. Although Taylor was always interested in the Franklin Furnace archive coming to Fales, he fully understands the decision to house it at Pratt. "Wilson wants it to live on," he said, "As an art school, Pratt has more flexibility. It is harder to be an on-going thing here."

Taylor and Wilson collaborated on the Martha Wilson: Downtown show at Fales, which together with the Performing Franklin Furnace exhibit, featuring 30 projects from the Franklin Furnace archive currently at the Pratt Manhattan Gallery, was organized by the Independent Curators International (ICI) and initiated by curator Peter Dykhuis. "The idea was to exhibit me as a complete person," Wilson said, "with half the show focused on Martha Wilson as an artist brain and the other half on Martha Wilson as an administrator." Martha performed at many of the venues, appearing in Los Angeles in her Barbara Bush persona.

At Fales, Wilson and Taylor installed images from her early performing art in the long corridor. There is A Portfolio of Models from 1974 with Martha as Housewife, Working Girl, Professional, Earth-Mother, and Lesbian: Martha in a curly wig with a can of soda, short skirt, and high heels; Martha in a plain dress, simple cardigan and sensible shoes; and Martha in a satin jumpsuit. "At one time or another, I have tried them all on for size and none has fit," the wall text announces. "All that's left to do is be an artist and point the finger at my own predicament. The artist operates out of the vacuum left when all other values are rejected."

At the end of the hall, there is a full size image of Martha Wilson as Tipper Gore. Why Tipper? During the Clinton years, Wilson watched the MTV inaugural ball video where Bill Clinton came out playing the sax, then Hillary, followed by Al Gore and Tipper. "The mood in the room changed when Tipper arrived. "They booed her off the stage," Wilson said, explaining that Tipper advocated placing a parental advising label on video. "Tipper's advice for the 1990s was just let me decide what is obscene and your work will sell like hot cakes." Wilson said.

Inside the larger space at Fales, there are vitrines with Wilson's daily diaries and a video by Britta Wheeler of "A Day in the Life of Martha Wilson," a series of photographs taken by Wheeler and accompanied by Martha reading excerpts from her journals. The journal entries chosen for the exhibit are bold and uncensored. "I was trying to be as honest as possible," Wilson said, admitting that this is the first time that these journal entries have ever been on view. "But so far no one is mad at me."

Certainly not Marvin Taylor who is thrilled that Wilson's journals are on display in his space and who transformed the gallery from one that housed a permanent installation to one that showcases materials drawn from the collection in 1995. From the start, Taylor understood artists' papers as being very different and he shrewdly built upon the foundation of NYU's collection of beat writers by networking extensively. By 1994, he had found his niche: downtown archival material from the 1970s and 1980s, especially important because the AIDS crisis had decimated the arts scene.

A friend directed him to Ron Kolm who had worked at various bookstores including the Spring Street Bookstore and who had lots of signed copies by writers. An admirer of Between C & D, an experimental and graphic publication, he added their papers to the archive. Most archives consisted of printed materials although the C& D cache arrived with the Downtown Collection's first digital remnants, floppy disks.

Donated to Fales by individuals and estates, the Downtown Collection grew in size and reputation, often by word-of-mouth but also often by dint of Taylor's extensive networking. One such example is the David Wojnarowicz's papers, which came to Fales in 1997. Taylor knew Robert Sember, a graduate student, who provided him with an introduction to Tom Rauffenbart, Wojnarowicz's partner. "When I first visited the collection in storage on 17th Street," Taylor said, "I saw "The Magic Box" and immediately understood that it was important for understanding David's practice. So, I accepted it along with other objects David had collected." It was a major breakthrough for Taylor because it changed his thinking about what archives can be, especially artists' papers.

Heavily used by researchers, the Downtown Collection today offers graduate students, in search of unique doctoral dissertation topics, and curators, impassioned by the growing trend to include original archival material in their exhibits, a treasure trove of printed matter and objects. The list is extraordinary, some might even say eclectic and exotic: there are papers from such downtown luminaries as Richard Foreman, E.L. Doctorow, Jack Gelber, Pete Hamill, Richard Hell, Frank Moore, Gary Indiana, and David Wojnarowicz; and archives from such in-your-face innovators as Gay and Lesbian Pulp Fiction, the A.I.R. Gallery, the Guerrilla Girls, Go Nightclubbing, Inc, Outpunk, and Creative Time.

Steeped in reading Foucault and Eve Sedgwick, a modernist who criticized the way libraries handled Queer material, Taylor and Evelyn Ehrlich, to whom he reported, understood that librarians had to become more allied with archivists.

The Downtown Show: The New York Art Scene 1974-1984 held in 2006 was a turning point for Taylor. In collaboration with the Grey Gallery at NYU and its director Lynn Gumbert, the exhibit recognized that archival objects had enough agency to stand on their own. The collaboration was synergistic, especially given Grey's history. Two years before the opening of MoMA in 1929, NYU was home to the A.E. Gallatin Museum of Living Art (1927-1943), a space developed to showing living artists. When NYU administrators decided to convert the gallery space into a library processing facility, the Gallatin Collection was sold to the Philadelphia Museum. Subsequently, Howard Conant and a group of artists and dealers began the NYU collection in 1958. Currently housed in Grey, it consists of about 6,000 pieces and is especially strong in the NY School from the 1950s and 1960s.

The collaboration between Grey and Fales was fortuitous and it cemented their mutual interest. "Marvin Taylor and I realized that "we shared a similar interest in looking at a broader overview of the arts -at a dissolution of boundaries," Gumbert said. "Marvin is so visionary," she said. "I always have enjoyed the notion of supporting materials. We foreground them."

Although Gumbert admitted to a minor curatorial disagreement with Taylor, who likes to line things up straight in the vitrines while she often prefers to fan materials out, she said that they agree on basics. Both are passionate about revealing the interior voyages of artists. "It is a way," Gumbert said, "of getting a broader understanding of art and its context and how it circulates."

In a sequel, Downtown Pix: Mining the Archives, (2010) another collaboration between Fales and Grey, they hired Philip Gefter, a photo curator, to go through the Fales photo archives to create a show. On the lower level of the Grey Gallery, they added snapshots by Andy Warhol, from the NYU collection.

Subsequent collaborations have included Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond, which was conceived of as a companion to Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life, a traveling show from Dartmouth, and Toxic Beauty: The Art of Frank Moore (2012. Scheduled for January, 2017 is a future collaboration, Inventing Downtown: Artist Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1963, which will be curated by Melissa Rachleff.

Today the competition to obtain archives has heated up and Fales goes up against the well-endowed Getty Foundation and Yale for archival material. Still, Taylor was there first and Gumbert believes that Taylor and Fales have "not yet received the recognition that they deserve." That's only partially true, though. When Alexander Campos, Director of the Center for Book Arts, introduced Taylor recently at a panel that Taylor was moderating there on archives, he noted Taylor's impressive official bio. Campos concluded with the fact that "Taylor was the only librarian to be promoted to the rank of full curator at New York University.

In the audience, Martha Wilson called out a very loud: "Wahoo!!!!!"

On view until April 30, 2015:

Martha Wilson: Downtown at NYU Fales Library,

3rd floor, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South

www.nyu.edu/library/bobst/research/fales/

Performing Franklin Furnace, Pratt Manhattan Gallery

144 West 14th Street, 2nd floor

http://www.franklinfurnace.org