On Sunday, July 3, the doors to the Barnes Foundation in Lower Merion, PA will close. Its priceless art collection will be taken down, wrapped and shipped to its new home in Philadelphia, a mere five miles away. Barring some last minute reprieve, the Sunday closing in Lower Merion marks the end of the Barnes Foundation as it was created and endowed by its founder to be, and another victory for greed, power and money über alles.

To fully understand the gravity and significance of what is about to happen in Philadelphia, Don Argott's 2010 documentary, The Art of the Steal is a must-see. The film, as entertaining and suspenseful as any who-dunnit, maps out the complex machinations of what has been called the world's largest art theft since World War II.

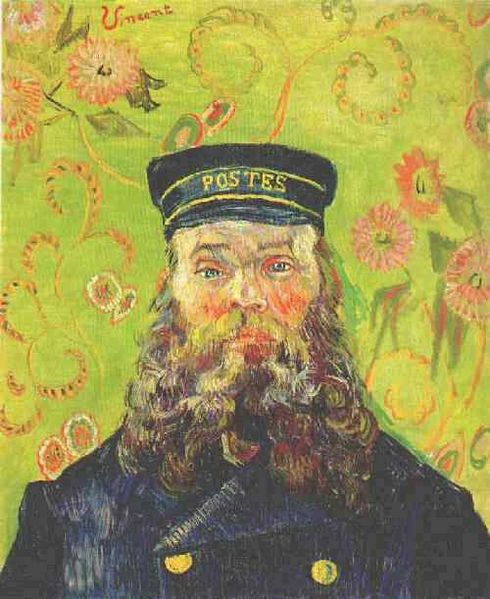

Albert C. Barnes' Post-Impressionist art collection is estimated today to be worth approximately $25 billion. The collection includes 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos, and 7 Van Goghs. The Barnes Foundation was never intended to be a museum. Barnes' will left specific instructions that the foundation would remain a school and that the work would never be loaned, moved or sold after his death.

Vincent van Gogh, Joseph-Etienne Roulin, 1889, 66.2 x 55 cm, The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

The Art of the Steal paints a vivid and convincing picture of an Albert Barnes who was infuriated by the ignorance of the cultural elite in Philadelphia, an elite who had publicly ridiculed his art collection when it was first shown. Barnes is quoted as saying "Philadelphia is a depressing intellectual slum" and "the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a house of artistic and intellectual prostitution." The film portrays Barnes' attitude as the driving force for creating his foundation in Merion, vowing that the "provincials" in Philadelphia would never get their hands on it.

In its rebuttal to the film the Barnes Foundation glosses over Barnes' hatred of Philadelphia society saying simply: "Any suggestion that Dr. Barnes situated the Foundation in Merion in order to keep it away from the area's elite or conservative art establishment is entirely unfounded."

I'm not convinced.

Barnes died in a car crash in 1951 and control of the foundation was left to Lincoln University, a small, under-funded, African-American school. The job of running the foundation fell to Barnes' right-hand person, Violette de Mazia, who ran the school as Barnes had intended for the next 30 years. Upon de Mazia's death in 1988, Richard Glanton, president of the board of Lincoln University, decided to take control of the Barnes. Understanding its revenue-producing potential, Glanton set out to get the Barnes the worldwide attention he felt it deserved.

Paul Cézanne, Nature morte au crâne, 1895-1900, 54,3 x 65 cm, The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

Claiming that the building housing the collection had been neglected, Glanton proposed selling off some of the art to pay for the cost of the repairs. Objections were raised that selling the work was illegal and unethical according to the terms of Barnes' will and the plan was abandoned. Glanton then came up with another plan, to tour the collection worldwide to pay for the repairs, also in direct opposition to the terms of the will. This time, however, Glanton prevailed and the first major attempt to chip away at Barnes' will was a fait accompli.

With the entire world now clamoring to see the Barnes collection, politicians, huge charitable trusts, rich socialites and tourism boards (all of whom declined to be interviewed for the film) swarmed in and fought to gain control of the collection and move it to Philadelphia. Eventually, $150 million was raised to fund the new facility in Philadelphia -- more than enough money to address any problems that the Merion location presented.

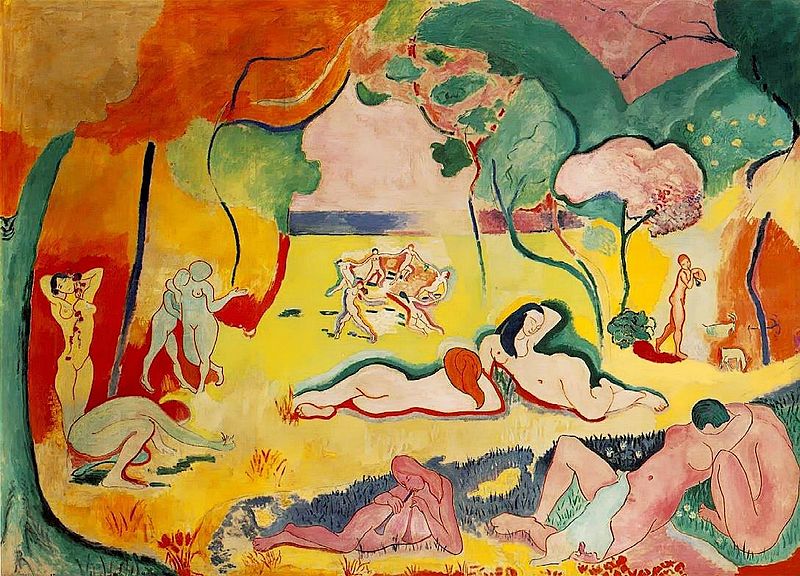

Henri Matisse, Le bonheur de vivre, Oil on canvas. In the collection of the Barnes Foundation. 175 x 241 cm

Fighting these powerful forces were a handful of artists, Merion residents, historians and lawyers. Interviewed in the film are LA Times critic Christopher Knight; Julian Bond, whose father, Horace Mann Bond, was the first black president of Lincoln University; John Anderson, author of Art Held Hostage; former student Jay Raymond and David D'Arcy, correspondent for The Art Newspaper. D'Arcy states:

"My feeling about Philadelphia is that it doesn't do itself justice saying 'we need to be a world-class city' by stealing an art collection and bringing it down to what I call a 'McBarnes' in downtown Philadelphia."

Henri Matisse, whose large site-specific mural, The Dance II, 1932, is being moved to the new facility in Philadelphia is quoted as saying: "The Barnes Foundation is the only sane place to see art in America."

. . . until Sunday.