These days every Land (state) election in Germany is international news. Whatever the outcome, the conclusion is always the same: the voters have punished Chancellor Angela Merkel for her generous refugees policies by voting for the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD). While the "AfD versus Merkel" provides a comfortable media frame, reducing a complex multiparty system to a two-horse race, it is simplistic and wrong.

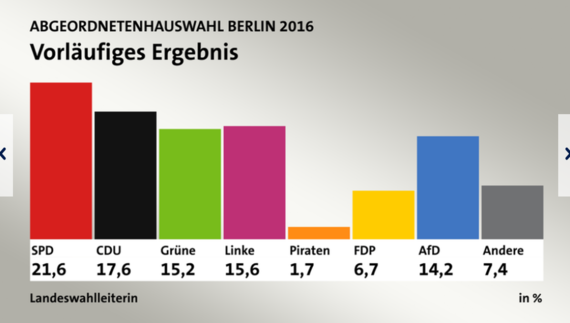

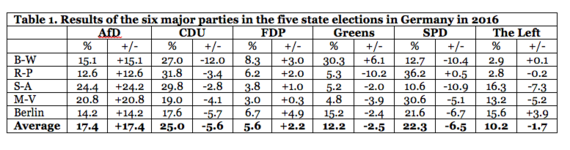

This year Germany held regional elections in five states: in Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate and Saxony-Anhalt on 13 March, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern on 4 September, and today in Berlin. Generalizing on the basis of these five states is tricky for many reasons, not least because two are in the East and Berlin is a unique political microcosm. This notwithstanding, here are some of the lessons we can learn from the 2016 state elections.

(1) The AfD always wins bigThe only constant in all state elections is that the far right AfD wins. However, the differences in the size of the victories of the AfD are almost as striking as the consistency of its success. The AfD score ranges from 24.2% in Saxony-Anhalt to (a predicted) 12.6% in Rhineland-Palatinate. Overall the AfD scores better in the East than the West.

(2) The 'big' parties always loose, often big

Merkel's Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has lost in every single state in 2016, while the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) lost in four of the five states - and it's only 'win' was +0.5%! In three states one of the two parties lost more than 10% of the vote, while together they lost between a mere 2.9% in Rhineland-Palatinate to a staggering 22.4% in Baden-Württemberg.

(3) The other opposition parties are strugglingThe only other party to win is each state is the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), but it rarely wins big. Its average result (5.6) is identical to the average losses of the CDU - a party that it is usually competing with. Moreover, the FDP remains a Wessie party, gaining little ground in the East.

Its mirror image is The Left, the successor party to the communist party of the former German Democratic Republic, which remains an Ossie party that is irrelevant in the West. It has lost big in the two Eastern states, where the AfD won biggest, and only did well in Berlin.

The Greens, finally, also struggle, despite the surprise win in Baden-Württemberg, where they lead the government. They lost in all other states, hovering around the 5% threshold in the East and West - except for Berlin, where they are traditionally strong.(4) The AfD wins from everyone, not just Merkel's CDU

It makes sense that if all parties loose most of the time and only one party wins all of the time, that party wins from all other parties. The voter streams in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern confirmed this at the individual level. The AfD gained 23.000 votes from the CDU, which accounted for only 16.5% of the total AfD vote. The Left lost 18.000 votes (13% of AfD vote) and the SPD 16.000 (11.5%), but the bulk of the vote came from non-voters (56.000 or 40%). In Berlin the numbers were very similar: 19% (CDU), 11% (SPD), and 32.5% non-voters. While it can be argued that the AfD takes these "non-votes" from the mainstream parties, they still take them from all other parties, not just Merkel's CDU.

(5) The time of the big parties is over

As most analysts have focused almost exclusively on the growing strength of the various new parties, they have largely ignored the correlated decrease in strength of the traditional "big parties." In 1980 the CDU gained 44.5% and the SPD 42.9%, together securing 87.4% of the total vote. In 1990, the first federal elections after unification, the numbers were 43.8, 33.5 and 77.3, respectively. In 2002 both parties won 38.5% (together 77%) and in 2013 it was 41.5% for CDU and 25.7% for SPD (67.2% together). A clear decline, but still a solid two-thirds of the total vote.

In the five state elections of 2016 the implosion of "The Big Two" has been almost complete. In only one of the five states do CDU and SPD get more than half of the vote together: 68% in Rhineland-Palatinate. In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern they dropped just under half (49.6%), while in the other three they hover around 40%! Perhaps most strikingly, in only one state does one of the parties gain more than one third of the vote: the SPD in Rhineland-Palatinate (36.2%).(6) Germany is set for true multi-partyism, with or without the AfD

Traditionally Germany was known as a two-and-a-half party system in the political science literature, meaning that the two big parties (CDU and SPD) needed one small (half) party for its coalition governments (the FDP). With the rise of the Greens in the late 1980s it became a two-and-two-halves party system, which was not fundamentally changed by the emergence of The Left in the 1990s, as it is excluded from coalitions at the federal level.

According to the results in the various 2016 state elections, as well as the opinion polls for the federal level, Germany has developed into a true multi-party system in which more than two parties will structurally be involved in the coalition formation process. With the CDU under 33% and the SPD under 25% a continuation of a Big Coalition will not only be politically risky, it might be mathematically impossible after the 2017 federal elections - as it already is in an ever growing number of states.

German voters are more and more mobile, looking at different parties as well as at not voting. They are also more fragmented, being divided over a growing number of small and moderately sized parties. One of the consequences is more challenging coalition-formation processes, which could lead to more frustration, and further strengthen old and new protest parties. This will be the case with or without the refugee crisis, with or without Merkel, and with or without the AfD!

[ The numbers for the Berlin elections and for the averages have been updated on the basis of the new predictions of the final results. ]