In every field of study, scholars are challenged by the question: How do you know? A historian might respond, "I read a lot of eyewitness accounts (which I list), called primary sources. I figure when enough people agree in their reports, that's gotta be what happened." A reporter might say, "I interviewed three independent sources, (whom I will not name) and they all told me the same story." But a scientist has a different answer to this question, namely: "This is what I did. If you do what I did, you'll know what I know." In other words, science is a way of becoming your own primary source. By doing all the procedures in my book, Science Experiments You Can Eat, you will probably experience what I experienced. My procedures are evidence for basic principles of science. But don't take my word for it. See for yourself. Discrepancies in results pose new questions and challenges. In science, how we know determines what we know.

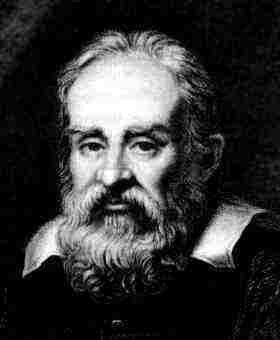

Galileo, (1564-1642) considered the Father of Modern Science, understood this. When he discovered the moons of Jupiter, he wrote a book called, The Starry Messenger. He promoted his book by taking it to dinner parties along with his very primitive telescope, which he had made himself. It only magnified 7x as compared to the 50X magnification of today's kids' beginner telescope. He encouraged dinner guests to look through the telescope to see the Jupiter's moons for themselves, something many folks were reluctant to do, fearing it was an "instrument of the devil." Galileo came to understand a profound truth about scientific knowledge and the public: People do not like to have accepted beliefs challenged. (Unfortunately, we haven't made much progress in this department.)

The word "science" is often used for the huge body of written knowledge about the basic laws and principles of nature that have been accumulating incrementally since Galileo. This knowledge is the product of thousands of people doing science to make discoveries through observations and experiments and sharing them with others. (For example, Galileo discovered Jupiter's moons by looking through a telescope at a specific location in the sky.) Ultimately, we collectively gather enough information to state a generalized law about the solar system. (Galileo's observation of Jupiter's moons was a tiny piece of evidence about the solar system that led the current, accepted heliocentric view that the planets orbit around the sun.) Now imagine being handed a thick and boring science textbook when you have no prior knowledge of science or how it was done. Suddenly, you are confronted with non-intuitive information using unfamiliar terminology that runs counter to everyday experiences; No wonder people think that science is difficult.

So why, then, do scientists and so many others, like children, love science? Let us count the whys:

1. It is challenging. Scientists must raise really good questions that reveal something unknown about something very familiar, like boiling water. For a cook, boiling water is easy to do and fundamental to preparing food. Put a pot of water on a stove and wait for the bubbles. But a scientist asks questions about this phenomenon that can be answered only by doing something more. What is the temperature of boiling water? Does it change once it starts boiling? If not, why not? Does water boil at the same temperature in Vail, Colorado as it does in New York City? If not, why not? Does water boil sooner if you put a cover on it? If so, why? Understanding boiling water was a huge breakthrough in science that led to the invention of the steam engine.

2.It is collaborative. Scientists share their procedures and discoveries by publishing papers. Other scientists can now repeat the procedures to confirm or dispute a finding. This is one reason why Science Experiments You Can Eat has become a classic. It is a book of procedures with my published results. If you replicate a procedure and get different results, you are not wrong. Nature doesn't lie. You got the results you were supposed to get. However, you now have the challenge of figuring out why your results are different from mine. This is how science works in real life. The process is self-correcting. When I researched my biography of Marie Curie I was struck by the eagerness with which she awaited the scientific journals that published her colleagues' work. She would greet the mailman and then run to her lab to repeat their experiments, thus deepening her own knowledge, giving feedback to her fellow scientists, and maybe giving her new ideas.

3.It is competitive (if you want it to be). There is only one nature to be discovered. Scientists who publish the most ingenious experiments and insightful results are widely read and win prizes. Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize twice. Some kids enjoy competing in science fairs.

4.Science discoveries are applied to solve problems for people. This is where engineering comes in. X-rays, light bulbs, phonographs, photographs, movies and telephones would not have been possible without science. If you understand the science, you can understand its applications. It is sooo very interesting!

5.Making discoveries is fun. This is by far the most compelling reason for doing science. Even if you discover something for yourself that others have already discovered, it's fun. Kids know it when they're having it.

A number of years ago, I recall hearing about a study of professional scientists, which found that most of them had been exposed to science and sustained an interest in it by fourth grade. That has been corroborated by a recent study that looks at the achievement gap in science between children from higher and lower-income families. It found that kindergarten children's general knowledge of the world predicted how well they would do in first grade and was also the strongest predictor of how well they would do in science in the third grade. After third grade, the science achievement gap was stable through eighth grade. There were no more converts.

In other words, start nourishing your children's interest in the world around them early, which means listening to (digesting) their questions and helping them learn to find answers that cook up more questions. As they get older, feed their interest with books and activities that help them make discoveries themselves. Professor Jourma Routti, an esteemed Finnish educator, once told me, "Education cannot be rushed. It's a law of nature. It takes nine months to make a baby and 33 years to make an engineer."

Note: In the interest of full disclosure, the latest updated and revised edition of my book Science Experiments You Can Eat will be published on July 5, 2016.