Zoologists like myself study the animal kingdom so we humans can develop a better understanding of animals and the role they play in maintaining our ecosystems. Zoologists also study animals so we can learn how to help conserve their populations. This has become critically important today, as more than 600 species are teetering on the brink of extinction. The cheetah, which is the animal that I have chosen to study, has a population of fewer than 10,000, down from 100,000 a century ago. With so many endangered species, scientific studies focused on animals' sexual reproduction, sexual behavior and mating systems provide invaluable data that aids in developing management strategies and setting conservation priorities.

Nature has slightly different rules for the dating game when it comes to the animal kingdom. Like with humans, monogamy, polygamy and promiscuity exist, but there are some idiosyncrasies that have to do with the fact that animals are guided more by natural instinct and less by what their parents may think of a prospective mate. Some species mate for life, like the bald eagle, the white-handed gibbon or the Kirk's Dik-dik, a type of African antelope (despite its name implying a penchant for multiple partners). Others are more "dating friendly," having many different mates over the course of a lifetime, and considered polygamous, like marmosets, whales and honey bees.

In the animal kingdom, three types of polygamy exist. When a male has exclusive rights to more than one female mate, the mating system is known as polygyny; when a female mates exclusively with several males during a breeding season it is called polyandry. Then there is the animal mating strategy polygynandry for which there is no human equivalent (unless perhaps you join a swingers' club or happened to be around during the Summer of Love), where two or more males have exclusive rights to two or more females, and the number of males and females does not need to be equal. About 90 percent of mammals are polygynous. It is the most common form of polygamy among vertebrates, including people.

No Love Lost for Female Cheetahs on Valentine's Day

In the animal kingdom, the dating game is male-dominated. But there are some notable exceptions, like the cheetah.

Female cheetahs do the choosing when it comes to their sexual partners. Their home range may be up to 10 times the size of a male cheetah's, so they will travel far and wide in search of a mate. Female cheetahs can bring themselves into heat (cheetahs are "induced ovulators," animals that ovulate based on genital stimuli and not cyclically), and female cheetahs control the mating rituals. On the savanna, females mark play trees with their scent and their claws, posting messages about their reproductive status near a group of males, a coalition, usually brothers. If one of the males goes to the play tree and urinates, defecates or sprays, then she knows he is interested. Then, the female will make her move, establishing visual contact. The male cheetah that is interested will move away from the coalition and meet her on mutual ground. No flowers or chocolates necessary for this romantic encounter.

Once a female has mated, she may stick around for a couple of days, but she will soon take off to give birth and live on her own. Her male partner will have nothing to do with raising the cubs. If the cubs are born healthy, the female cheetah may return to the same partner in a couple of years to mate again, but it's likely this may be their only meeting. Female cheetahs are fiercely independent animals that live, hunt and raise cubs entirely on their own. They only need the males for one thing, and when that is done, it's sayonara.

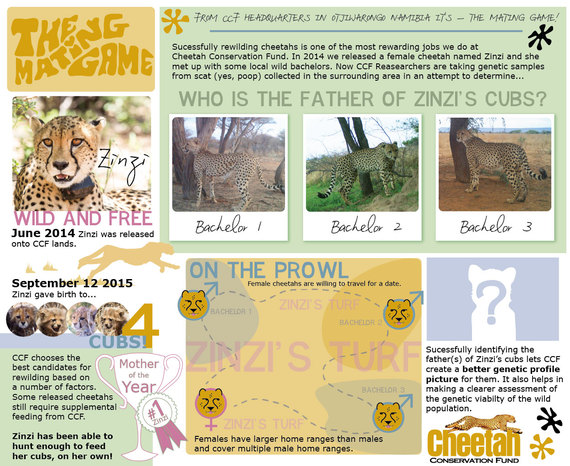

While we are addressing this subject with a bit of humor, the study of reproductive behavior at Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) is one of our research imperatives. The data we mine from our studies informs our cheetah conservation strategies and in the case of animals that have been rewilded, helps us establish a measuring stick for success (if a cheetah has been rewilded and is mating and breeding, then the re-wilding effort is considered successful). Establishing paternity for cubs of rewilded mothers gives us a clearer picture of their genetic profile and provides key data to help us understand the local wild population.

In 2009, CCF scientists began experimenting with scat detection dogs to assist with cheetah genetic relatedness, census and demographic research. Dogs have 200 million scent receptors in their noses, compared to humans, who only have 15 million, so they can smell much better than we can and smell things we aren't able to see. Scat provides genetic identification through DNA, which can then be extracted from the scat. Together with camera traps, we use cheetah scat to determine the presence of cheetah in the area, and to learn more about those individuals, their relatedness and behavior. Scat provides so much valuable data, it has earned the nickname "black gold" among researchers.

At CCF, we also conduct biomedical research to help us monitor the wild cheetah population's genetics and health. We systematically take blood, tissue and sperm samples from all of the cheetahs that we come in contact with and add them to our Genome Resource Bank. Nearly 1,000 cheetahs have been sampled since 1991, making ours one of the largest genome databases for any endangered species. This genetic information, accompanied by ecological and ecosystem research, guides us in developing science-based strategies to manage cheetah populations and establishing priorities for cheetah conservation throughout their range. From this database, we might also identify the father of our rewilded mother's cubs.

Maybe yet another reason we zoologists study the birds and the bees in the animal kingdom is to learn something that informs our human experience. Observing the mating game of the female cheetah, my dating policy about buying my own drinks has been validated.