Voters have been bombarded for months with information designed to influence their choice in the 2012 presidential election. From news stories to blog entries to tweets, nary a second goes by that some loaded nugget about the candidates is not being propagated to the electorate. Nonetheless, the polls have remained remarkably flat over time, fluctuating little over the course of the general election campaign. So, what gives -- is the public immune to this colossal effort to shape their presidential preferences? Not quite, but as our research shows, changing aggregate opinion is a slow process, where criticisms pack far more of a punch than compliments.

Mitt Romney Received More And Better Coverage Than Barack Obama

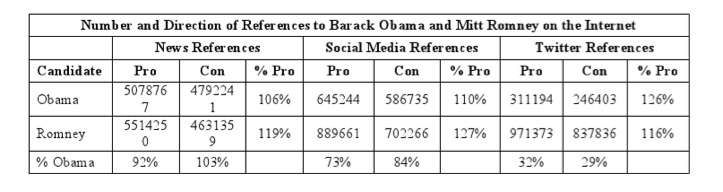

General Sentiment, a social analytics company, tracks content on nearly all publicly available informational websites on the Internet, which considering the overlap between offline and online media provides a good proxy of campaign coverage overall. It covers news sites, such as Foxnews.com and The Huffington Post, to social media, like blogs and forums, to Twitter posts. For each sentence generated by these sources, General Sentiment also scores its polarity, namely the extent to which the sentence is positive, or negative.

We isolated those sentences appearing in the media from Oct. 1, 2011 through Nov. 1, 2012 in which the name of Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney or Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama appeared. Then, we computed the proportion of sentences making positive and negative references about each candidate. Sentences that did not yield a pro or con reference were omitted from our analysis.

We found there were far more persuasive statements propagated on the Internet about Romney than Obama. Romney held a 3-to-1 advantage over Obama in the number of polarized tweets disseminated on Twitter. Nearly 30 percent more slanted references were made about Romney than Obama on social media, such as blogs and forums. Romney even received slightly more sentimental coverage on news media websites.

Positive references were greater than negative references for both candidates across all three media types. Romney held an advantage in positive references on both news websites and on social media. Obama only had an advantage on Twitter. The results were roughly the same if we only considered the general election campaign, running from the party conventions to the present.

Public Opinion Changed Little Over the Course of the Campaign

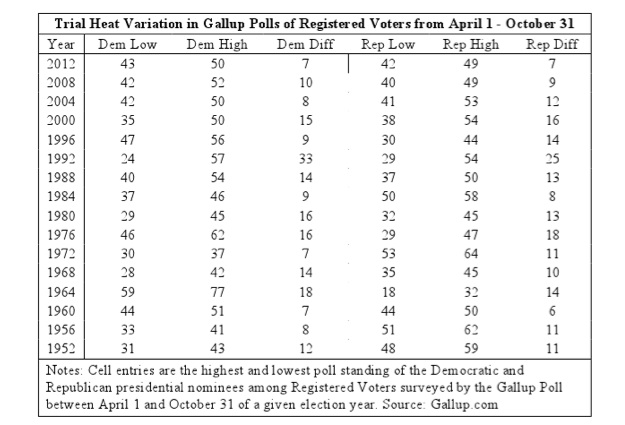

Despite the steady stream of persuasive information, presidential preferences have changed remarkably little over time. The Gallup Poll shows little change in the vote choice of registered voters throughout the general election campaign. Since April when Romney emerged as the clear-cut Republican nominee, the proportion of registered voters supporting Obama has fluctuated between 43 and 50 percent, while Romney's standing has varied between 42 and 49 percent. There has been even less variation since the campaign hit full throttle at the start of October, as both candidates numbers have swung with a 4-point range.

In fact, the 2012 campaign has shown the smallest amount of variation of any presidential campaign in the last fifty years. Since 1952, the average change in support for the Democratic nominee has been roughly 13 percentage points, while the average change in support for the Republican nominee has been roughly 12 points. The last time there was as little change in support for the major party candidates during the campaign cycle was the race between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960.

Impact on the Race

To determine the impact of the presidential campaign, we examined the impact of polarizing information about each candidate on the Internet on their respective standing in the polls. Using all the publicly released trial heats from Oct. 1, 2011 to Oct. 17, 2012, we categorized respondents as either preferring Obama or Romney or Neither. The Neither category included all respondents who did not support either of the major party candidates. We applied the well-tested ideodynamic model to predict the movement over time between these groups as a function of the positive and negative references identified by General Sentiment about each of the candidates. Predictions were made from the model every 24 hours as new information arrived to change opinions.

The ideodynamic model contends that more positive information about the candidates pushes respondents toward their camp, while more negative information pushes voters away from them. Consider, for example, respondents who prefer Obama (PObama(t)). Positive information about Romney (IRom+(t)) and/or negative information about Obama (IOba-(t)) is hypothesized to move respondents preferring Obama (PObama(t)) toward preferring Neither candidate (PNegative(t)). Conversely, negative information about Romney (IRom-(t)) or positive information about Obama (IOba+(t)) is hypothesized to move respondents preferring Neither candidate (PNegative(t)) toward preferring Obama (PObama(t)). Information is hypothesized to work in the same way on respondents preferring Romney.

The results of our analysis show that most of the change in aggregate preferences during the 2012 presidential campaign was from undecided voters opting to support either Obama or Romney. There was little net movement of supporters away from their preferred candidates.

We found that the principle driver of public opinion change was negative information about the candidates. Favorable information produced little movement in aggregate preferences. Messages unfavorable to Romney drove undecideds toward Obama while messages unfavorable to Obama moved undecideds toward Romney.

The prevalence of negative coverage (or the lack thereof) about the candidates at several key moments in the campaign generated most of the fluctuations in the polls. Obama got a much bigger bounce coming out of their respective conventions. Favorable Romney coverage from the Republican convention was not accompanied by anti-Obama messages, so it ultimately had little impact on the race. Obama's coverage, on the other hand, was not only positive, but yielded more negative coverage of Romney when the Democratic convention was compared to the Republican convention. This negative information about Romney drove up Obama's support gradually over time as undecided respondents moved into his camp.

The gain for Obama was stopped by the discussion of his poor performance in the first debate. Most of Obama's drop in the polls was due to supporters adopting an undecided position. All the while, there was a small, steady stream of anti-Obama information that continued to push Romney up in the polls, but at a very slow rate.

Obama's slide ended after the last debate. Since then, persuasive information has yielded little additional change, in the range of 1 percent. As of Nov. 1, the model predicted Obama would secure 47 percent of the vote, compared to 46 percent for Romney. Seven percent of the electorate still preferred neither of the candidates.

In sum, for all the resources poured into the presidential campaign, most has been for little effect. Public opinion responds slowly to persuasive information, akin to carving the Grand Canyon one raindrop at a time. Perhaps more disheartening is that shifts in aggregate preferences are due more to negative information than positive information. While many complain about the extent of negative campaigning during the presidential races, there is a reason it continues to be so widespread: it works, as we have shown using a time trend method that complements other methods studied.