Cross-posted from Medium

Universal tax credits could be the much needed bipartisan tool to spur growth and boost the income of most Americans

My father, born in 1932, grew up in rural North Carolina as the son of a textile worker and golf course manager. My mother's dad ran a corner grocery while her mother worked as a seamstress in a furniture factory. Over the course of their lives, my parents both got college educations, became professionals, and moved into the middle class. By the time they had me, they believed that their hard work would continue to pay off and make for a better future for their son. They could never have imagined the prosperity that our family enjoys today, nor could they conceive that in 2016, a reality-TV star turned politician could be so close to the Presidency.

Changes in our economy and society in recent decades have shattered the myth of linear economic progress for the average American. A narrow few have benefited from advances in automation and globalization and changes in our tax code, while the vast majority of Americans have languished in a 30-year period of economic stagnation. In my own career I have watched dozens of young people go from coders to millionaires -- sometimes billionaires -- nearly overnight. This was the story of the Facebook founding team that I was a part of, and it's been the story for thousands of other entrepreneurs at technology companies. There have always been rich people in America, but there is no historical precedent for the swiftness and scale of wealth creation for a concentrated few today.

The new economy that churns out Facebook and iPhones has not created mass prosperity: median incomes have stagnated and household debt levels have risen. Three quarters of Americans, a record number, now believe the next generation will not be better off than theirs.

This mass stagnation is fueling the rise of political extremes here in America and across the developed world. Traditional liberal policy solutions -- investment in education or infrastructure and expansions in unemployment insurance -- would strengthen our economy, but they are incremental steps and politically infeasible today. Yet a potent idea that would quickly and effectively jumpstart the economy sits in plain sight: cash for all. An aggressive, multi-year tax credit program today could appeal to the left and right alike and would have positive and immediate effects on the lives of struggling Americans.

Unfortunately rehearsing the details of the dire economic situation of most American households has become old hat in certain circles. Headlines say the country has recovered from the financial crisis and that companies are making record profits, yet everyday Americans' paychecks have not budged. This isn't just a problem from the past few years; economic populism is exploding in the United States because median incomes have not increased in decades.

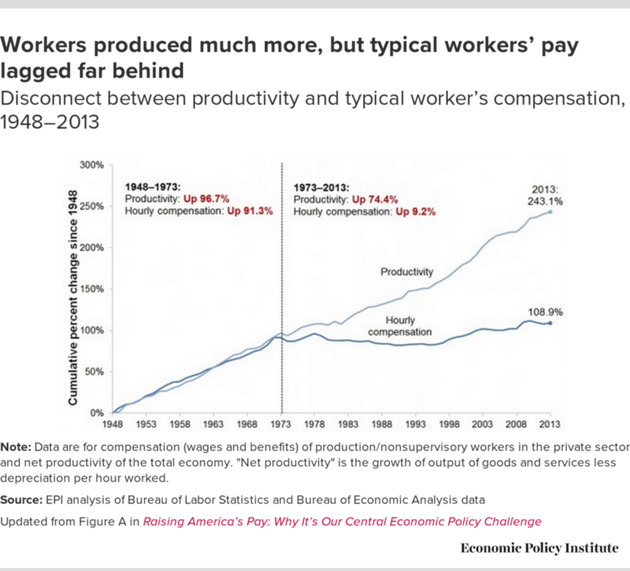

Since 1973, workers' pay has stagnated while productivity and overall wealth have continued to rise. Median household incomes today are the same as they were 20 years ago, even though our economy has doubled in size. The machines at airport check-in counters and call center workers in India remind Americans nearly daily that automation and globalization have fundamentally transformed how wealth is distributed. Alongside these trends the weakening of organized labor and a more regressive tax code introduced in the 1980s also likely contributed to our mass stagnation. Just as there are many causes, there is no single silver bullet for a permanent solution.

The mainstream liberal response to today's predicament is to expand traditional social programs. Unemployment insurance and food and housing assistance need urgent investment, as do primary and secondary education and job retraining programs.

There are two problems with the existing approach to safety net expansion. These programs are expensive, difficult to implement at scale, and at best are a patchwork solution to a wide range of challenges that lower and middle class families face. The return on investment in the programs is difficult to isolate and measure and takes time to appear. Secondly, given Republican skepticism of government spending, expansion of these programs is perceived as a partisan issue. Any kind of broad-based investment in the existing social safety net would only come to pass through overwhelming Democratic majorities, likely alienating much of the American electorate in the process. As much as some on the left or right would prefer to wait to act until their party is in total control of government, American voters rarely grant that kind of one-party dominance. Genuine engagement with policy solutions to stop mass stagnation will have to appeal to at least some major factions on both sides of the aisle.

Universal tax credits for every American meet the demands of Republicans who want lower taxes and less government bureaucracy and the demands of Democrats who want to reinforce the social safety net. As a bipartisan policy, these tax credits could be the perfect departure point for the next President and Congress to find rare common ground. A universal tax credit program of $1,000 each year for the next three years to all American adults might just be politically feasible and would certainly be massively impactful.

There are two ways to view the effect these tax credits would have: the human impact on the lives of American families and the macroeconomic effects on the economy. A little over a year ago, TIME and Money Magazine put to their readers the question "What would you do with an extra $1,000?" and got a wide and inspiring variety of answers. They ranged from practical uses, like paying off student loan debt or buying a better pair of glasses, to inspiring ideas like buying a wedding band or enrolling in a community art class. No one saw an extra $1,000 as life-transforming, but the variety and thoughtfulness of the responses illustrate the need and power of an unexpected cash infusion to help people make ends meet and pursue their goals.

Economically speaking, a cash infusion of this scale and size would have major, positive economic effects. Dubbed "helicopter money" by conservative economist Milton Friedman nearly 50 years ago, direct cash infusions into the pockets of all Americans would be a powerful instrument to spur consumer spending and bring inflation back in line with historical rates. In a prominent article from last month, The Economist argued for central banks to consider handing out cash directly to citizens, highlighting the evidence that quantitative easing of this nature would have strong positive effects on stagnant economies and likely not lead to excess inflation.

Put simply, in a time when all other economic stimulus tools have been tried or filibustered and median incomes have not budged, cash transfers could be the necessary spark to improve the standard of living of American households.

Fortunately in the United States there is recent precedent for helicopter money's effectiveness and bipartisan appeal. In the spring of 2008 as the country teetered on the brink of what would become the Great Recession, a bipartisan majority in Congress approved a rebate plan that George W. Bush signed into law. Over the course of the spring of that year, all American adults making less than $75,000 received a check for $600 in the mail. While it wasn't enough to stave off the recession, research in following years showed that it was a powerful boost to the economy with between 50 and 90% of the funds being spent by recipients, much of it on durable goods.

We should build on that experience, but go significantly further and provide $1,000 per year for every American adult for three years. The cost at this scale would be about $230 billion per year, 1.4% of GDP and a bit larger than the size of Bush's rebate.

To be effective, tax credits need to be consistently and universally distributed and not tied to any conditions. Universality would ensure that everyone in society benefits, creating a sense of collective investment similar to Social Security. The wealthy could choose to opt out altogether or to donate the funds to those who need it more. When the assumption is that everyone in society benefits from the credit, the political conversation becomes about spurring consumer spending and not about the poor "free-loading off of hard-working Americans." Peter Barnes, in his argument for long-term dividends for all, makes the case for universal benefits convincingly:

"Universality . . . unites society by putting all its members in the same boat. The income everyone received is a birthright, not a handout. There's no means test and no penalty for working. This changes the story, the psychology, and the politics. No one is demonized, and a broad constituency protects the system from political attack."

Similarly, tax credits have the distinct advantage of being open-ended and unconditional, ensuring that people can use the money for their most urgent needs rather than setting up government in the role of nanny state. For the skeptics who doubt that the average American would know how to use the money well, research into other cash transfer programs demonstrates that less than 1% of cash transfers is spent on alcohol or drugs, and most of the funds go to housing and food costs. Studies from across the world also show that cash transfers do not discourage work as many skeptics fear.

How can we pay for a tax credit program of this magnitude? Barnes recommends a carbon tax to sustain his program of long-term social dividends, arguing it would at once price the culprit of climate change and provide the funds to reduce the burden of rising energy prices. Increased income taxes on the top 1% would be another straightforward and fair way to finance the program, although politically difficult. Another option would be to coordinate the transfers with the Federal Reserve, as some economists, including Ben Bernanke, have considered. The Fed would increase the overall money supply similar to what it did in previous quantitative easing programs, but this time the cash transfers would support American households directly rather than the balance sheets of large financial institutions.

Some would argue that this kind of temporary credit would not be enough. The movement supporting a basic income -- recurring, unconditional cash payments -- has blossomed in recent months, and a number of countries have begun to consider providing all their citizens with an income of $10,000 or more. Canada, Finland, New Zealand, and a region of The Netherlands have all started to research or experiment with a universal basic income. Momentum is growing for a social dividend in the United Kingdom, and next month Switzerland will hold a referendum on whether to provide a basic income to all its citizens.

I'm supportive of the idea of a basic income over the long term and believe that one day something of this size will likely be necessary to cope with the impact of automation and globalized trade on the United States. But the reality today is that kind of intervention would be unaffordable and impractical: a benefit of $12,000 per adult would cost just shy of $3 trillion annually, about 75% of the entire current federal budget. Beginning with a modest, but universal tax credit would help millions of Americans and build a framework for future investment. The effects of these cash transfers could be further studied and provide the basis for a potentially permanent establishment of a basic income. Just as a previous generation built Social Security gradually over the course of years, all of us who support a basic income should think about what a practical start on the road toward it might look like.

Other critics take the opposite view and argue that a program of this scale would be too large, too costly, and too risky in a period of tepid economic recovery. We have spent years providing cheap and easy money to major financial institutions while ignoring the structural economic changes that are keeping down the middle class and poor. No doubt we need further analysis and research to produce more specific estimates on the total cost and additional economic effects of these programs, like additional tax revenue and changes in inflation. But without this kind of major intervention, economic growth will likely continue to lag and American households will become increasingly skeptical of the current political and economic order.

If the federal government does not take action, states and cities should lead the charge as they have on so many issues to prove the power of these credits. Twenty-six states already have their own earned income tax credits that supplement federal programs, and the pipes already exist to provide state tax credit checks to qualified residents.

Multi-year tax credits will not solve all of our problems. They cannot bring back lost manufacturing jobs or retrain workers for the jobs of the future. But when paired with other policy solutions, they could be the necessary stimulus to help American households exit a seemingly never-ending cycle of stagnation.

Without bold action, the fallout from mass stagnation will continue to wreak havoc on the social fabric of America. The surprising strength of Bernie Sanders' campaign and Donald Trump's victory in the Republican primaries should be wake-up calls that traditional policy ideas are not resonating with middle class voters. A growing number of people in America feel the American dream is dying, and stock answers from an entrenched elite won't bring it back. Donald Trump's anti-trade, anti-immigrant, nationalistic rhetoric may be superficial and bawdry, but its wide appeal speaks to the disillusionment of millions of well-educated, middle class Americans.

His cynical prescription for America needs a clear rejoinder that matches its boldness in order to break through the noise of today's political conversation. Investment in education, infrastructure, and job retraining programs are all critical, but we have to advocate fresh, creative ideas like cash for all if we are going to bridge the partisan divide and restore our collective faith in the American dream.