Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

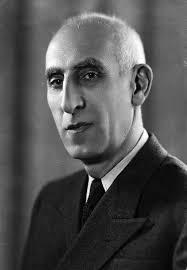

Mohammad Mossadegh (pictured) became Prime Minister of Iran in 1951 and was hugely popular for taking a stand against the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British-owned oil company that had made huge profits while paying Iran only 16% of its profits and often far less. His nationalization efforts led the British government to begin planning to remove him from power. In October 1952, Mosaddegh declared Britain an enemy and cut all diplomatic relations. Britain looked towards the United States for help. However, the U.S. had opposed British policies; Secretary of State Dean Acheson said the British had "a rule-or-ruin policy in Iran."

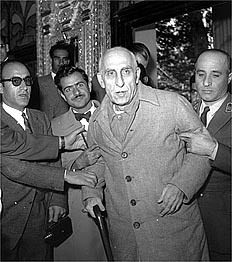

That changed after Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President in 1952. Beginning in January 1953, the U.S. and Britain agreed to work together toward Mosaddegh's removal. The plot, known as Operation Ajax, centered on convincing Iran's monarch to issue a decree to dismiss Mossadegh from office. But the Shah was reluctant to attempt such an unpopular and legally questionable move. He finally relented, after much persuasion and bribes to his family.  On August 16, 1953, the Shah formally dismissed Mossadegh and nominated the CIA's choice, General Fazlollah Zahedi, as Prime Minister. Soon, massive protests, engineered by the U.S., took place across the city to assist the coup. The coup not only encouraged the Shah's descent towards dictatorship, it would later become a rallying cry in anti-U.S. protests during the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

On August 16, 1953, the Shah formally dismissed Mossadegh and nominated the CIA's choice, General Fazlollah Zahedi, as Prime Minister. Soon, massive protests, engineered by the U.S., took place across the city to assist the coup. The coup not only encouraged the Shah's descent towards dictatorship, it would later become a rallying cry in anti-U.S. protests during the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

This account was compiled from interviews done by ADST with Lewis Hoffacker (beginning in July 1994), third secretary at Embassy Tehran from 1951-1953, John Stutesman (June 1988), a consular/political officer at Embassy Tehran from 1949-1952, and David Nalle (April 1990), Director of the Bi-National Center

Read the entire account on ADST.org This piece was edited by S. Kannan

HOFFACKER: The Shah was on the throne. It was rather shaky because [Mohammad] Mossadegh, the Prime Minister, was hanky-panking with the Commies. And we, Uncle Sam, could not tolerate any of that. Iran was too important.

So our goal was to support the Shah and to try to contain Mossadegh, who had certain crazy qualities, or what some people would call crazy qualities. He was unbalanced, to say the least.  It came to the point where the CIA became very prominent in the process of supporting the Shah and of containing Mossadegh. Mossadegh exiled the Shah and the Shah had to come back. And the Shah was a gentle man, very gentle. We called him a "weak reed" because he needed a lot of guidance.

It came to the point where the CIA became very prominent in the process of supporting the Shah and of containing Mossadegh. Mossadegh exiled the Shah and the Shah had to come back. And the Shah was a gentle man, very gentle. We called him a "weak reed" because he needed a lot of guidance.

He needed a lot of help, and we helped him, gladly. Of course, he changed to something different later on, and that was a problem, in a way. He was talking about creating a "white revolution," trying to bring Iran into the 20th century with heavy foreign aid. And we were heavy in foreign aid and heavy in military aid.

There was no problem with the CIA trying to bring down a government or bringing in a government. We did that more or less routinely; this was the pattern in Iran. And it was easy to justify, because you couldn't give Iran to the Commies, who were there already. The British were kicked out, and we were filling that gap.

STUTESMAN: Indeed, this just may be my memory, but I don't think that Mossadegh and the majority of the Persian people who supported him were that concerned about the oil. What they were concerned about was throwing off the British yoke.

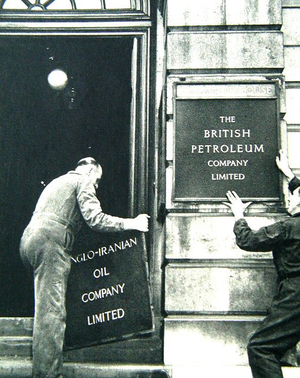

Mossadegh, I believe, expected to be rescued by the Americans. I don't think he expected to be left alone. He thought that he could drive out the British, that the Americans, like any respectable competitor, would welcome that, would happily move in and sell his oil. We didn't do it, and he fell. The AIOC [Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now British Petroleum] was absolutely hand-in-glove with the embassy people. In fact, I think it would be fair to say that the AIOC had a much more dominant influence on British policy in Iran than the diplomats in the embassy. The AIOC used money, used old connections, they used them brutally. I don't mean physical brutality, but just without much deftness. This began to change as it became clear that the AIOC was simply incapable of handling the political difficulties.

The AIOC [Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now British Petroleum] was absolutely hand-in-glove with the embassy people. In fact, I think it would be fair to say that the AIOC had a much more dominant influence on British policy in Iran than the diplomats in the embassy. The AIOC used money, used old connections, they used them brutally. I don't mean physical brutality, but just without much deftness. This began to change as it became clear that the AIOC was simply incapable of handling the political difficulties.

Q: The British were taking an obdurate position in the talks with Mossadegh and the Iranian Government. Did Grady make any efforts to convince the British to take a more flexible approach to the Iranians?

STUTESMAN: [Ambassador] Grady would just groan when he would be writing his reports and talking with us. He would groan at the stubbornness of the British, the blankness of their minds when it came to dealing with Iranians. I would say he was probably much more angered and frustrated by the English than he was by sweet old Mossadegh. Although Mossadegh was a far more dangerous foe.

My own personal feeling is now, and was then, that Mossadegh had absolutely no intention of settling with the British on any terms that the British could accept, despite his several offers of such settlements. I don't think that Mossadegh ever wanted to do anything except give the British a bloody nose and, along with it, went his abiding assumption that the Americans would take care of him.

So I stand on my belief that the American oil companies did not mount any kind of conspiracy to get the British out of Iran. I do think that Mossadegh expected them to take care of him.Mossadegh worked in the belief that the Americans would not allow Russia to control Iran. The Americans were the new power and owed nothing to the British, Mossadegh felt that if he kicked out the British and threatened the Americans with Russian hegemony, that we'd rush in. He wasn't that far wrong; we did in the end.

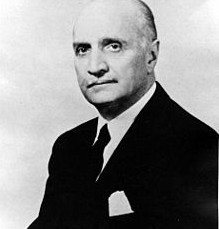

By the time Henderson (pictured) came, it had been clear that almost all avenues had been exhausted. I don't think he had instructions when he arrived, to develop an overthrow of Mossadegh. I think he came instructed to try to restore some steadiness to a situation which was a very difficult situation. But I believe that Mr. Henderson had a deep reluctance to have a covert operation displace a chief of state. I think he had a long-term reluctance and a long-term sense of uneasiness about what this might do to the future. At the same time, I think that he faced a situation where there was very little alternative to the departure of Mossadegh.

But I believe that Mr. Henderson had a deep reluctance to have a covert operation displace a chief of state. I think he had a long-term reluctance and a long-term sense of uneasiness about what this might do to the future. At the same time, I think that he faced a situation where there was very little alternative to the departure of Mossadegh.

The decision to overthrow Mossadegh was made, I believe, by [Walter B.] "Bedell" Smith, who was then Under Secretary and who had come from the post in CIA, and who had been Chief of Staff to Eisenhower, so that you had a very tight family relationship there.

You had Eisenhower as President, John Foster Dulles as Secretary of State, his brother Allen as the head of CIA, and Smith having been the closest associate of Eisenhower during the war and having been the deputy in CIA, now as the deputy in the State Department. So when Bedell spoke, he spoke not only with direct instructions, but also with a deep understanding of what his principals were thinking.

I certainly was not present, but I've been told this by someone who was present, that CIA officers were in his office discussing Mossadegh, and Bedell, who had a very bad stomach problem, may have clutched his stomach and groaned, or he may have said, "Dump him." (Laughs) But I have a feeling the decision was made that easily and that quickly, and then CIA went to work.

I really don't think that our policy on Iran was worked out, certainly not on the basis of any conspiracy, but on the basis of sort of, "Well, Jesus, what do we do now? Oh, okay, let's get rid of him. Now -- oops! Okay, we've got to give him some money."

And then the workers go to work, Henderson and some of the others. Having said that I believe he was deeply reluctant, Henderson's role was nonetheless to carry out policy, and he very carefully developed an attitude and helped to sponsor an attitude in Iran that Mossadegh was leading the country to ruin and to Communist control.

NALLE: The removal of Mossadegh was, in my estimation, a tragic mistake on the part of the United States.

But essentially, the seeds of that revolution were planted then, because we insulted the Iranians nationally, as a nation. Who knows what might have happened had Mossadegh stayed on, if we and the other forces that removed him had not come into play? It would have been a mess, because Mossadegh really didn't have control of the country or its various economic problems. But it would have been an Iranian mess, rather than one we created, and they would have worked it out in some way. It's a very sophisticated country in many ways. It was then and still is. They would have worked out a path to being a modern country, which they have not become. It might not have pleased us, and they might have been -- although I don't think so -- more friendly to the Soviet Union than we would have liked in the Cold War, but they are much more afraid of the Soviet Union than even we are, for good reason.

It would have been a mess, because Mossadegh really didn't have control of the country or its various economic problems. But it would have been an Iranian mess, rather than one we created, and they would have worked it out in some way. It's a very sophisticated country in many ways. It was then and still is. They would have worked out a path to being a modern country, which they have not become. It might not have pleased us, and they might have been -- although I don't think so -- more friendly to the Soviet Union than we would have liked in the Cold War, but they are much more afraid of the Soviet Union than even we are, for good reason.

So we interrupted the normal course of Iranian history. Iran would have gone its own way, and we would not have become the scapegoat, the great Satan, or whatever.