When we are beginning a journey towards a clean economic future, the choices for those first steps will have echoing resonance for years to come. In past generations, we made assumptions about our economy and our society that fit with the spirit of those times. Our challenge now is that this 20th century spirit is haunting our present, and thus threatening our future. The past spirit was one of conquest and manifest destiny followed by a grand ambition to build a "modern" infrastructure through our electricity systems and our interstate highways. The spirit was one of growth as the momentum needed to maintain our prosperity, and the power that we used to fuel this manifestation of our ideals was reliant on very large scale operating systems to ensure that all of our citizens had access to energy and electricity. This momentum was blind, and we used our creativity to accelerate the conversion of fossilized sunshine to consumables and the movement of people and products, generating electrons in abundance to ensure access to energy. Fast forward to the 21st century, and we still are using a fire hose to water a flower.

We are only 13% energy efficient in this country, which means we are blasting energy towards our needs in such a way that 87% streams right by us. Obviously, we need energy to create the systems that ensure our quality of life. But in order to create an infrastructure for the 21st century, we cannot be hindered by the ways in which we thought in the 20th century. Last century, regulation was geared towards access, affordability and reliability, with no thought to the source of the power in question. The only strategy for access was to create as many electrons as quickly as we could. Energy was a commodity, and the electricity we used as a society was largely invisible. Right now, we rely on an electricity infrastructure that is made up of entities that call themselves utilities and whose mission space is firmly rooted in the concept that the greatest goal for these activities is access, affordability and reliability. These bodies of people and technology build a system that serves us electrons we use to power our local economies. The overall infrastructure is comprised of power generating plants that distribute that power through massive transmission and distribution lines that are monitored through sub-stations and that are regulated broadly by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and more regionally by public utility commissions and other regulations if the power company is privately owned.

Of course, the whole lumbering behemoth is much more complex than I've described it. But the fundamental basics are accurate. The way that system was built to power us in the 20th century is reflected in the architecture of the technology and of the regulatory requirements for the participants. We create an overabundance of electrons because we are asking the wrong questions in our dialogue between electron creators and electron consumers. Like our obesity problem, we are creating an overproduction of "carbs," where we are feeding our needs like someone who is not paying any attention to the nutrition content of what we are eating, not to mention the number of calories we are ingesting. To be competitive in a global economy, we need to be smarter about our energy choices here at home.

In order for our economy to get back in shape, the first thing we should think about is cutting calories: let's tackle the energy efficiency problem. But there needs to be a strategic basket of multiple reform measures based on the qualities of those that are starting this diet. The very basic premise in these conversations is that in order for a utility to have any utility in a competitive economy, it needs to fundamentally change from a McDonald's franchise to a Weight Watchers corporation. On a recent broadcast, a manufacturing CEO was talking with Stephen Colbert about how her product can't compete with one made overseas and she lamented, "Our energy costs for production represent 26 cents per unit when they can sell the whole unit for 23 cents..."

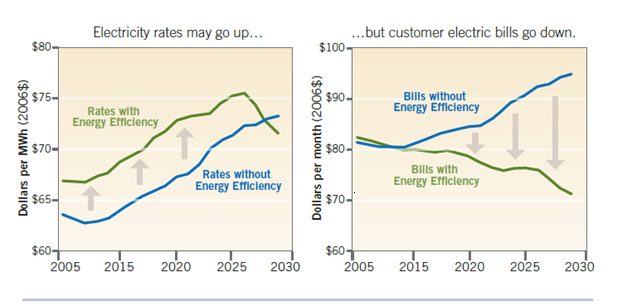

(Graphic source: Tom Eckman presentation BPA Utility Summit March 17, 2009)

So let's imagine what our global economic competitiveness would be if after our diet we were able to leanly offer production at a fraction of the costs we bear right now. In other words, the energy programs that go into place to make us more efficient may make our rates go up to pay for these new opportunities, but once in place our utility bills decrease because we're using fewer electrons. What if our utilities were in the business of providing the services we require to manage our energy in the most efficient way possible and when necessary, provide us with "healthy" energy choices (choices that reflect the health of our long term success, see this previous post for a discussion on the harmful nature of excess fossilized sunshine)?

Instead of slopping electron gruel from a trough that is brimming over, let's start reading the label about where our electrons are coming from and how many we are using. This "energy intelligence" has been observed to be a very necessary part of a realistic transition from fossilized sunshine to a clean energy infrastructure. Where utilities have already shown their utility in this part of our path forward takes place in the role it plays in the ratepayer's home or business. Thor Hinckley, who manages the renewable power programs at Portland General Electric, is justifiably proud of how he feels their work has raised what he calls the "energy literacy" of his customers, injecting some knowledge into an American population that have relatively little to no idea where or why power comes to them in its current system. "PGE has started a dialogue about where energy comes from. We can tell the story of how much comes from coal (a surprising 23% in a state where there is so much hydropower) and we give our customers the option of 100% renewable. When we have this conversation, the minute where the customer checks in with themselves they have a couple of different reactions: (1) Now they have new information (so it's not all hydropower); (2) the climate issue and concerns are told with the context of where energy practice is driving some of the negative factors associated with the climate issue and (3) they have the choice to choose a clean energy option."

When it comes to the nexus between energy consumption and energy choices, it is fair to say that a utility has almost "perfect reach" into this demographic as the arbiter of electrons themselves. That reach starts me thinking about the new business models that could be introduced; imagine the GMAC model where in this case, maybe the new mandate means that energy service companies could perhaps get into the business of offering consumer financial products to help finance retrofits. It is the choice this arbiter makes to engage in this conversation that fleshes out who is closer to the Weight Watchers model, and who is still peddling the dollar menu.

Commodity perspectives on energy prevail in what has been called the "mega-utility" model, where unlike the regional approach that PGE and other utilities have, the scaled-up utility has issues with identifying itself as a regional service; instead, the model functions by keeping us in the dark about our energy nutrition. Now, if you are McDonald's and you want to sell Big Macs, of course you don't broadcast your calories and triglycerides (am I asking for a lawsuit from McDonald's and Duke Energy in one breath?) To be completely fair, if you are a conglomerate utility functioning in service areas that traverse multiple state lines, and whose regulatory agency only focuses on affordability, access and reliability, you are in a somewhat constrained position. Flipping the equation, it is much easier to some extent to have a municipal utility where the citizens collectively own the service and the regulatory body is represented by the city council. At least within that arena one can create a Weight Watchers plan to implement as they move away from the McDonald's model. That said, just because a utility is local does not mean that it necessarily is enhancing the energy literacy of its service area. Rural co-ops, where the utility is a cooperative run usually by a very insular group of decision-makers, represent a truly sharp and double edged sword. On the one hand, you only have to convince this small group; on the other, there is usually absolutely no way to use any sort of leverage with these guys other than persuasion. Since even the most risk taking utilities have an enhanced immune system to change, the co-ops represent a fairly significant challenge.

Bob Gough, Secretary of the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy, recognizes that co-ops, "are trapped economically and politically." He goes on, "As long as energy was cheap, we didn't have to recognize that energy touches every part of the economy." And another fundamental disconnect between where we are now in the 21st century and what we've built upon, "It's a frustrating state of affairs when twenty year long term contracts are put in place to ensure stability and reliability, and the participants therefore cannot capture the value of the accelerated rate of the evolution of ideas and technologies." It also should be noted that as those technologies have evolved, innovations in financing the upfront costs have blossomed alongside ( see this article for a previous perspective on what we mean by "expensive energy.") Kitty Wang of the Rocky Mountain Institute shared her thoughts with me, "We are really looking at a vision of the future where we'll see ways to build out a low carbon, centralized path for power generation with utility scale clean energy power plants, while we'll also see incentives for distributed generation where smaller facilities will be located closer to where the electrons are needed."

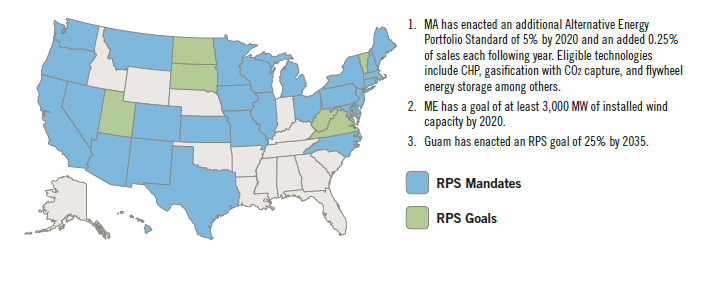

Julia Hamm, president and CEO of the Solar Electric Power Association (which in turn represents the intersection between the solar industry and the utility industry), has told me her organization believes that utilities have to be 100% integrated into the process of creating a clean energy infrastructure. "A lot of the answer has to point back to changes in the regulatory context where utilities do business," she says. "In the case of solar, I really believe those utilities that are not as far along on the learning curve have to be given the right rules which remove the disincentive and add incentives." Two powerful policy mechanisms are decoupling for the carrot side of the conversation and renewable portfolio standards for the stick persuasion. Indeed, where the carrots and sticks are in place, a clean energy infrastructure seems to make more business sense. ICE Energy has an innovation that addresses the drain that air conditioning puts on the grid within a utility's service area, in a way that allows the existing utility infrastructure to function more efficiently thereby mitigating the need to expand production capacity. They have gotten significant traction in California, where public utilities are working within a state economy that has made significant advances towards providing a "real price" of energy within their communities and thus can make the decision to engage a clean energy solution more readily. California is attractive because they have a large demand for energy from air conditioning, they have an economy that has a more realistic price for energy in a globally carbon constrained environment, and they have a consuming public that is more energy literate than those in other parts of our country. ICE Energy has a harder time engaging a large investor owned utility (IOU) servicing a territory that has not realistically priced energy, which is really too bad when we realize that the entire South East uses a great deal of air conditioning, with a backwards looking view on what a price for energy should be (no real carrots or sticks in quite a few states below the Mason Dixon line).

(Graphic source: Navigant Consulting)

A big issue in terms of the haunting spirit of the 20th century is that our whole electric grid was designed for centralized, controlled power plants running on a continually available feedstock, not for intermittent renewable distributed widely across service territories, and certainly not to be able to help the end user understand where the power was coming from. So if Julia is right about the need for 100% buy-in by utilities, we will have to create the right regulatory environment in which they do business. Which means the regulators, the consumers, and the utilities themselves will have to be fully engaged in the challenge.

I have to say I am an optimist, but that future seems ambitious even to me. I think it is going to be more realistic to put in place replicable models of changing the conversation, whether that is a more robust campaign to help our citizens become energy literate, combined with a federal decoupling policy for all domestic utilities, combined with an accelerated national energy efficiency portfolio standard, and some way to un-grandfather long term contracts so that our infrastructure is not weighed down by the 20th century. If the global landscape and the competing interests there are the ultimate "sport" of the alignment of resources and opportunity to maximize the success of the citizenries within those borders, we don't want to be weighed down as the lumbering competitor; we want to be lean and fierce. Ultimately, the utility of a utility is realized when it focuses first and foremost on delivering negawattage while transitioning to clean megawattage in the most cost effective way possible. Hold the cheese, give me the treadmill.