Many years ago, in a land far, far away (Los Angeles in 1968, Robert F. Kennedy has just been assassinated and Apollo 8, the first manned space craft to leave the Earth's orbit has beamed back images of "Earthrise" from the far side of the moon) two young men set off on a journey to portray the experience of perception. These two men, Robert Irwin and James Turrell, joined the psychologist, Ed Wortz who conducted experiments in ergonomics (how humans interact with technology) for NASA missions, in order to collaborate on an experimental artwork. They wanted to design a Ganzfeld sphere, a chamber that would deprive visitors of sound and reduce light to mere grey field. They wanted to use art to alter the way an individual perceived his or her surroundings, bringing them into an experience where it was virtually impossible to differentiate between seeing and imagining. First though, they invited participants into an anechoic chamber: a dark, soundproof room where these individuals were left completely alone for 10 minutes. During that time the visitors reported experiencing states of hallucination and time distortion. They reported hearing their own heartbeats and the sound of blood going through their veins. They saw colors and "light shows" that appeared out of nowhere.

Though both Irwin and Turrell approached this encounter with darkness as an experiment in the nature of perception as a medium for their art, and though both emerged continuing to play with perceptual ambiguity, the experience of the Ganzfeld effect (Ganzefeld in German means entire field) sent them in opposite directions. In 1969, a few months after the Eagle Landed and Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, Turrell mysteriously abdicated during the experiment and took his name off the project. Later he said, "When we want to go into the universe, we can't look at a rock, like the Japanese. We have to actually go to the moon. We're so literal..." But to look at Turrell's work today, one has the sense that he is the one who never truly left that chamber. For whether his spaces are infused with hot neon pink or cold white, he is still fascinated with the illusions that occur when space is controlled by the presence or absence of light.

As for Irwin, upon leaving the chamber he reported, "the trees were still trees and the street still a street, and the houses were still houses, but the world did not look the same; it had very, very noticeably altered." Unlike the ethereal Turrell, Irwin was not as concerned with the hallucinations that happened inside the chamber, as he was with what occurred once the room was left behind. What could be called the viewers re-experience of the incidental, concrete world.

Robert Irwin began as a minimalist painter, creating large-colored canvases with a few horizontal lines running across the surface, but soon he began to question the mark, the canvas and the frame as a container for meaning. By the time he met up with Turrell, he'd already gained renown for his disc paintings. Circles of aluminum sprayed with matte acrylic and mounted 20 inches from the wall that played with optical uncertainty. "I slowly dismantled the act of painting," he wrote, "to consider the possibility that no-thing ever really transcends its immediate environment."

By 1970, a few years after the Ganzfeld chamber, Irwin wrote. "I began again simply getting rid of my studio and all its accompanying accouterments and saying that I would go anywhere, anytime. In response." He wanted to create site conditional art. In a world saturated with spectacle, he wanted his art to respond to the existing surroundings so that the viewer's experience of the everyday world would become paramount.

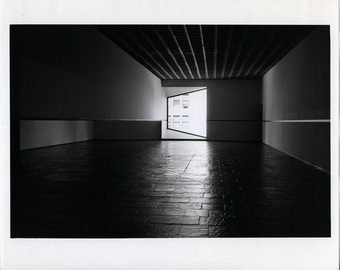

Scrim Veil -- Black Rectangle -- Natural Light is just such a site-specific piece. First conceived and executed in 1977 and for the Emily Fisher Landau Gallery on the 4th floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Scrim Veil has now been resurrected. The occasion for this reinstallation is to bid a fond farewell to the magnificent Modernist building designed by Marcel Breuer that will be turned over to the Metropolitan Museum next year when the Whitney relocates down to the meatpacking district. And so this piece is temporal in nature. It may belong to the Whitney collection, but it was designed only for a room that will no longer house the Museum.

As it was in 1977, the 117-foot-long room has been stripped down to its essence: the grid of the ceiling, the dark rectangle of the floor, and the light emanating from the window. The only object to occupy the space is a suspended scrim of white transparent polyester fabric hanging 5 ½ feet from the floor weighted by a black metal bar. Around the room, delineating the perimeter of the walls runs a black line that is also 5 ½ feet from the floor. That's it. Room, window, ceiling, floor, scrim and line of black, these are the only elements in this work of art. But taken together these simple components manipulate the viewer's sense of perception. At times the translucent scrim appears transparent, at others, opaque. It advances, then recedes, continually casting and recasting the rectangular room and the trapezoid window in a new light.

Stepping off the elevator and into that room is to have ones awareness of the brutal modernist architecture of Marcel Breuer heightened. At first certain, then confused, ones visual sense begins to expand. Never before has Breuer's space felt so full of possibility. A window looks like a projection, a see-through scrim like a solid wall. Nothing in that room, or once one steps outside again, can ever be taken for granted.

Robert Irwin (b. 1928), Scrim veil -- Black rectangle -- Natural light, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1977. Cloth, metal, and wood. Overall:

144 × 1368 × 49 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of the artist. Photograph © Warren Silverman

James Turrell

Twenty blocks north, James Turrell has reconfigured the Guggenheim. Unlike Robert Irwin whose work is designed specifically for a particular environment, James Turrell thinks nothing of modifying his surroundings to suit the needs of his vision. His spaces are elaborate theater-like constructions often controlled not just by recessed lighting, but by computer generated programs.

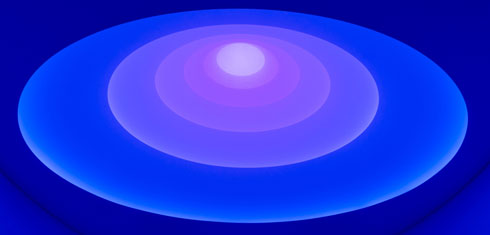

In Aten Reign, James Turrell has returned to his early work with Robert Irwin and transformed the Guggenheim, turning the Rotunda into a giant Ganzfeld chamber. With a virtually unlimited budget, he has built a conical-shape scrim scaffolding and infused the Guggenheim with indeterminate light. At times a hallucinatory encounter, luminous and atmospheric, the space of the Rotunda alternately vaults the viewer heavenward and pulls the eye socket shaped skylight down so that it feels like it is hovering just beyond our reach. As befitting its title -- Aten is the sun-disc deity in ancient Egyptian mythology, while reign of course means supreme -- Aten Reign is probably the grandest declaration of light as pure presence as is humanly possible.

James Turrell, Aten Reign, 2013

Daylight and LED light, dimensions variable. © James Turrell

Installation view: James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 21-September 25, 2013. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Turrell, a man with a flowing white Moses beard, has been working on his own labyrinth of stargazing rooms in an extinct volcano (the Roden Crater in Arizona) for going on 39 years -- nearly as long as Moses took wandering the desert. From his Quaker origins, through his work as an aerial cartographer, then his studies in astronomy, mathematics and perceptual psychology at Pomona College, he has never wavered from his dream to embrace light. He is truly like Moses or Fitzcaldero, a man with an obsessive vision pulling his dream over -- or in Turrell's case through -- a mountain.

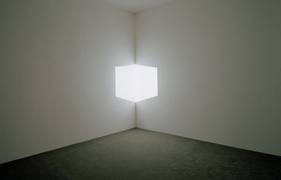

When Turrell last exhibited in New York it was fall, 1980 and during the time that his show was installed at the Whitney, John Lennon was shot and killed. Back then, Turrell's light spaces were dark rooms altered with just a pure stream of white light that made the corners of the space turn into floating shapes, and shafts of light look like doorways into sacred chambers. There are a few of these early pieces on view at the Guggenheim now and when I saw them again, I was reminded of that long ago Whitney show in 1980 when I felt certain, as one does when is barely out out of one's teens, that if John Lennon had truly disappeared from our planet, he'd gone through Turrell's tunnel of light to inhabit one of those brilliantly lit spaces. That's what Turrell does. He makes you believe in the promised land. He brings it close enough so you can almost touch it, but of course you can't touch a possibility, you can only look for it.

James Turrell, Afrum I (White), 1967. Projected light, dimensions variable

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Panza Collection, Gift 92.4175 © James Turrell

Installation view: Singular Forms (sometimes repeated), Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum, New York, March 5-May 19, 2004. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

For years now, ever since 1980, I have been thinking about both Robert Irwin and James Turrell and the mutability of not just things, but space itself. I have thought of how these two singular artists came together to consider perception and how they then diverged. Each in his own way reminds me of what babyhood must have been like, when the world was distorted because it was still unnamed and unknown. After viewing Irwin, I feel as if I've awoken to the concrete world for the first time. After Turrell, I experience the possibility of manifest apparitions -- moments that are hallucinatory even ecstatic, because of the way he imbues empty space with a presence as thick as a dream. I can't tell you in which world I'd rather exist -- for they are contingent on one another -- only that the wonder is that they are each possible, and I am once again grateful to behold both visions before my eyes.

Robert Irwin at The Whitney Museum from June 26-September 1, 2013

James Turrell at The Guggenheim Museum from June 21-September 25, 2013