Installation view of "When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South" (Jacolby Satterwhite, Satellites, 2014), The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2014 (Photo: Adam Reich)

Installation view of "When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South" (Jacolby Satterwhite, Satellites, 2014), The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2014 (Photo: Adam Reich)

Currently on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem is an art exhibition that displays the rich variety of African-American visions of the South. Organized by the museum's Assistant Curator Thomas J. Lax, "When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South" sets aside conventional art world categories of insider and outsider art, and instead explores across different media and disciplines how 35 black artists in the last 50 years have made art inspired by and deeply imbued with southern cultural legacies. With religion and music as hallmarks of southern culture, it is satisfyingly fitting that the title of the exhibition comes from the chorus of a beloved African-American spiritual about the rapture and the beginning of a new dawn. This exhibition is Lax' last one at the Studio Museum, as in August he will be working at the Museum of Modern Art as an Associate Curator in the department of Media and Performance Art.

The spirit of magical power regarding change, creation, rebirth and hope (or the divine, if you will) inhabits much of the art in this exhibition, whether made by David Hammons, Beverly Buchanan, Ralph Lemon, Lonnie Holley, Trenton Doyle Hancock or Thornton Dial. It is a revelation to see how artists in far-ranging circumstances -- from upper echelons of the art world to junkyards, prisons, or home confinement -- attest to the beauty, ugliness and inspiration in their lives. And organizing such an exhibition requires a visionary mind capable of thinking outside the art world "box." In this show, Lax displays folk and outsider art alongside established fine art because doing so provides a more complete picture of visual expressions regarding an already loaded subject matter and highlights interesting, less-known qualities about these works.

Lax received an AB from Brown University and an MA in Modern Art from Columbia University. He has written artist monographs for venues throughout the U.S. and internationally, and is a faculty member at the Institute for Curatorial Practice in Performance at Wesleyan University's Center for the Arts. A generalist in post-war American and international art, Lax has nevertheless gained significant experience presenting art in performance, video and other forms of new media. He has worked with some of the most exciting artists working today, and the list of exhibitions he has organized includes: "Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art" (2013/14: New York curator; exhibition originally organized by Valerie Cassel-Oliver at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston), Fore (2012), "Ralph Lemon: 1856 Cessna Road" (2012), "Mark Bradford: Alphabet" (2010) and "Kalup Linzy: If It Don't Fit" (2008).

As Lax began preparing for his transition to MoMA, he thoughtfully discussed with me this exhibition and his journey as an exhibition-maker.

Julie Chae: Thomas, congratulations on your new job at the Museum of Modern Art and for all the excellent exhibitions you have curated at the Studio Museum, including "When Stars Begin to Fall." Let's start from the beginning -- how did you get involved in art?

Thomas J. Lax: I grew up at the heyday of the culture wars in New York immersed in a wide range of cultural experiences with my parents, from experimental theater and cabaret to history museums and contemporary art exhibitions. I have many memories of going to a variety of cultural institutions as a child -- El Museo del Barrio, the Jewish Museum, MoMA, American Folk Art Museum, and Schomburg Center -- which inevitably shaped my understanding of the functions and possibilities of libraries and museums within the broader culture world.

JC: Was there a particular point in your life when you decided you wanted to organize art exhibitions?

TJL: I had what Oprah would call my Aha! Moment in Lorna Simpson's moving retrospective at the Whitney. I was a recent college grad working with local LGBTQ youth of color organization FIERCE, looking for a job that might be relevant to what I had studied in Africana Studies and Art-Semiotics (good luck!). I had been shaped by incredible cultural critics including Anthony Bogues, Réda Bensmaïa and Saidiya Hartman, and was struggling to find a form of public engagement that responded to what felt to me to be totally urgent in the cultural politics of that moment.

The experience of seeing Lorna's work was profound, sensuous and core-shaking. Knowing that someone had orchestrated it gave me an intense sense of desire to craft that kind of experience with and for other people.

Installation view of She, Seven Months, Bio, 5 Day Forecast, You're Fine and Wigs II from the exhibition "Lorna Simpson" (March 1-May 6, 2007), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Photo: Sheldan C. Collins)

JC: You worked on an earlier show that included folk art from the Studio Museum's permanent collection and gained a real appreciation for art by so-called "untrained" artists. What does a show about the South, both real and imagined, gain by the inclusion of such outlier art? Or conversely, what would a show about the South lose by excluding art by these artists?

Installation view of "Collected. Propositions on the Permanent Collection" April 2, 2009 to June 28, 2009, The Studio Museum in Harlem (Photo: Adam Reich)

TJL: If you look at the iconic texts of twentieth-century American culture -- Jean Toomer's Cane (1923), Jacob Lawrence's The Migration Series (1940-41), Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man (1952) to name a classic few -- the South has been positioned as at once a place of origin, exile and return within the African-American imaginary. Similarly, black intellectuals who have struggled to identify whether there was or wasn't such a thing as a "black aesthetic" have looked to the South and to practices by self-taught artists alike. While much of this debate has been structured by a polemic between narratives of authentic or essential collective black identity on the one hand and individual narratives that eschew these ideas in the name of irony or humor on the other, I was interested in seeing if I could bring these two seemingly distinct sides together.

The show is an experiment to create a context in which the presumed terms of black orthodoxy -- Southern identity, vernacular art and religion -- could be named with their full sense of experimentation, funkiness and gnarliness. At the end of the day, I don't know if there is such a thing as "black art," but perhaps we can still use it as a term. It can serve as a kind of placeholder that can be filled with various content, together examining ways of working that emerge from subjective experiences of black people and in black places, which America certainly is.

(L) David Hammons, Untitled (Bottles), 1985, Cigar, dirt, balsa wood, tinfoil and mixed-media figurines in glass bottles, Dimensions variable, Collection of Hudgins Family (Photo: Adam Reich)

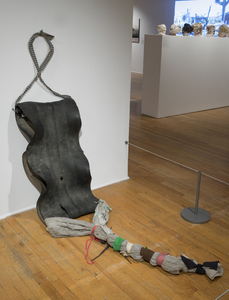

(R) Lonnie Holley , Blown Out Black Mama's Belly, 1994, Rubber inner tube, cloth and wire coat hanger, 84 × 22 × 4 in., High Museum of Art, Atlanta, T. Marshall Hahn Collection 1996.40 (Photo: Adam Reich)

JC: And what have you discovered?

TJL: What's been amazing to me about the show is the way in which contemporary artists of African descent like Kara Walker, Theaster Gates or Kerry James Marshall who we might think of as firmly within the contemporary art world, have channeled the figure of the self-taught as what I understand to be a kind of avatar for themselves. Whether through their interest in nineteenth-century history painting or in their desire to materially change the conditions of those in their communities, their identification with self-taught artists speaks to how the institutional naming of "outsider" artists as such is closely bound up in issues of representation for artists of color more generally.

Theaster Gates, Billy Sings Amazing Grace (video still), 2013-14,Video, color, sound, TRT 00:13:00 (Courtesy the artist)

TJL: One could also say that both insider black artists and self-taught artists are asked to "be real" -- display real suffering, make illustrations of that suffering, and offer the possibility of real salvation. Often, they are both denied the qualities of ambivalence, irreverence and desire for art-making that is distinct for illustration granted to other artists. The opportunity to show this group of artists together demonstrates the overlaps and differences of their artistic contexts, and hopefully points to some things that are quite visible or obvious within the art world but go unnamed.

(L) Beverly Buchanan, Tribute to Juanita, 2011, Wood and glue, 17 3/8 × 18 5/8 × 11 ½ in., Collection Jane Bridges (Photo: Adam Reich)

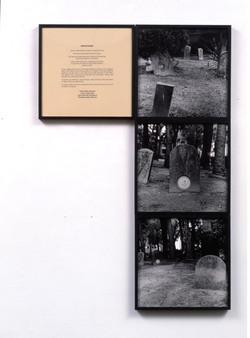

(R) Carrie Mae Weems, Boneyard (from the "Sea Islands" series), 1992, Three gelatin silver prints, one text panel, 20 × 20 in. each, Edition of 2 (Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

JC: It's interesting how it was your work and conversations with groundbreaking artists in performance and new media, like Ralph Lemon and Jacolby Satterwhite, that led to your conceiving a show about the Old South and folk art.

TJL: The impetus for this show came out of the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to work with choreographer/conceptual artist/writer Ralph Lemon for his exhibition "1856 Cessna Road" at the Studio Museum in 2012. That exhibition looked at his work with Walter Carter, an octogenarian sharecropper turned gardener turned performer who lived in Little Yazoo, Mississippi. Ralph described to me the way he saw Carter's hundred-plus year history from Jim Crow to the 2000s articulated through his bodily comportment.

(L) Ralph Lemon Untitled, 2013-14, Archival pigment print, 30 × 24 in. (Courtesy the artist)

(R) Ralph Lemon Untitled, 2013-14, Archival pigment print, 24 × 30 in. (Courtesy the artist)

JC: I think it's this ability to create alternative, even impossible visions of our world that I admire about artists. It is incredible given the history of the Black Belt region in Alabama/Mississippi -- the cotton plantations and slavery, that Lemon and Carter created scenarios with characters like Killer Space Dog as well as B'rer Rabbit-inspired tricksters. And the other artists?

TJL: At that time, I was chatting with other artists working in performance who themselves had intimate working relationships with creative visionaries not necessarily in the contemporary art world: Geo Wyeth, Jacolby Satterwhite, Xaviera Simmons, Malik Gaines and Alex Segade of Courtesy the Artists. They were likewise recuperating cultural associations based in the South, and doing so toward fundamentally experimental, process-based ends.

(L) Jacolby Satterwhite, Satellites, 2014, Vinyl wallpaper, Dimensions variable, (Courtesy the artist, Photo: Adam Reich)

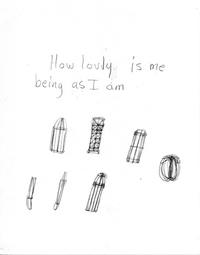

(R) Patricia Satterwhite Untitled (How lovely is me being as I am), c. 2008, Graphite on paper,

11 x 8 ½ in. (Courtesy Jacolby and Patricia Satterwhite)

JC: Within your field of American and international post-war art, you've developed significant expertise in performance and multi-media art. In the different areas of art you research and present to the public, are there perhaps some underlying questions you find yourself exploring?

TJL: American artists of color, artists working throughout the global South, feminist and queer artists, as well as artists who work in performance are making some of the most exciting work right now. If I were to sum up my perspective, I would say that what motivates my work is an investigation of the ways social contexts -- be they racial, geographic or interpersonal -- are subtly embedded in how we read and interpret formal decisions artists make. Conceiving of cultural information and materials this way allows for both a sense of reverence to the place and time in which is work is made, as well as a sense of play on my part as I create new contexts as a curator.

I think I'm also motivated by a deep dissatisfaction with the concept of the "political" in contemporary art. It's a word that is often thrown around, and to be honest, it's a word that I don't use often because at this point it has little meaning. Yet, its overuse points to its importance, so if I were to try and define it, I would say that political work embraces uncertainty, contradiction and a lack of established form. In this way, it is truly contestable.

Installation views of "Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art"

November 14, 2013 to March 9, 2014, The Studio Museum in Harlem (Photo: Adam Reich)

JC: What is it about performance that you find vital and challenging?

TJL: What I think attracts me to performance not only as a medium, but more fundamentally as a way of working, is that it is inherently intermedia; in other words, it needs other media like video, photography or sculptural props for its interpretation by an audience. This makes it dependent not only on a physical and spatial context but also on its spectators to give it cultural value. This is a microcosm of the more general phenomenon about what a museum does, which is fascinating to me. In this way, crafting a performance has some analogies to the ephemerality of exhibition-making, which informs my perspective on conceiving shows even if they are not exclusively performance-based.

Installation view of "David Hartt: Stray Light" March 28, 2013 to June 30, 2013, The Studio Museum in Harlem (Photo: Adam Reich)

Installation view of "David Hartt: Stray Light" March 28, 2013 to June 30, 2013, The Studio Museum in Harlem (Photo: Adam Reich)

JC: You've recently accepted a position as Associate Curator at MoMA in the Department of Media and Performance Art. And you've told me how fortunate you are to have been trained in the curator-as-collaborator model of exhibition-making from mentors Naomi Beckwith, Kellie Jones and Thelma Golden and to have learned from Lowery Stokes Sims, former Studio Museum director and current curator at the Museum of Art and Design, important values and insights about art world categories and relationships. I think it's wonderful you'll be bringing these values, approaches and insights with you to MoMA. What are some of the things you plan to work on there?

TJL: For the past seven years, I've loved being at the Studio Museum, where I've had the opportunity to work closely and committedly with artists whose work I believe in deeply. I am excited to bring my relationships and these experiences to MoMA, and to situate the artists, thinkers and scholars in a broad and generative way. In particular, I'm eager to consider what the increased scale of this museum means not simply in terms of visibility but in terms of audience, participation and spectatorship, which are issues artists are thinking through in their own work. I'm also excited to work closely with my new colleagues to think strategically about the specific place MoMA occupies in the incredible and robust world of performers, performing arts institutions and performance scholars here in New York. Finally, the department is the newest curatorial department at MoMA, and the status of performance in the context of museums is one that institutions around the world are actively reimagining. I'm thrilled to be able to take risks and build scholarly contexts in an institution that can influence the understanding and sense of possibility performance can offer for audiences, curators and artists throughout the city and globally in ways that are both specific and meaningful.

----------------

Note: This is the latest in my series "The Cultural Landscape Architects," profiles of art world professionals who play a role in connecting art with the public. They decide which artworks by which artists to present, place the art in the contexts of both art history and current times, and help shape the cultural landscape.

"When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South" is on view until June 29, 2014 at The Studio Museum in Harlem: http://www.studiomuseum.org/exhibition/when-the-stars-begin-fall-imagination-and-the-american-south