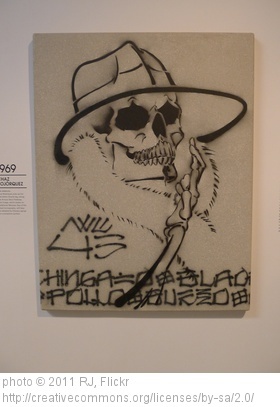

In the '60s and '70s, while radical, militant, and educated Chicanos were graduating from universities, going to art schools, and setting up organizations which would facilitate their entry into mainstream society, their less-motivated counterparts were advancing street gang organizations and using wall space to paint their own political slogans. Murals depicting ethnic solidarity and struggle were side by side with cholo graffiti, which was inspired by old English, Bauhaus block letters, and abstract lettering, thus creating their own cryptic medium that was then duplicated throughout the Los Angeles County. While Judy Baca was creating one of the longest murals in the world in the San Fernando Valley area of the L.A. River, depicting the Dust Bowl Journey, Japanese American internment, and the Zoot Suit Riots, another emerging artist, Chaz Bojorquez, was creating his own street art in the Northeast area of the L.A. River and the Arroyo Seco. Directly influenced by the ecology of his environment, Chaz took from the surrounding community of the Chicano graffiti culture and art and created one of the first forms of stencil art in Los Angeles. He had traveled to Mexico and Europe and saw what other artists were doing with stencil work, so he took the Zig-Zag man and juxtaposed it into a skull face, added a fedora and fur coat, and crossed his fingers to symbolize good luck. The piece known as Señor Suerte, was soon taken as street folklore and protection used by many gang members in the Highland Park area, specifically the Avenues gang.

Chicano street graffiti had always been considered uncultivated, lowbrow, and subversive, yet this type of urban artwork was present in ancient civilizations like: Greece, Rome, Egypt, Turkey, and Mesoamerica. Similar to other disenfranchised cultures throughout the world and civilization, they used this type of imagery to mark territory, establish community, convey ideology, and garner understanding. After all, that is what art is about, understanding the message. As a youth I remember driving all over the city and county of Los Angeles and being completely challenged by the non-linear perception of this type of medium. As I recall, three neighborhoods stood out the most in regards to the mastery of imagery and font. These neighborhoods took this style and gave it extreme flare, precision, and dimension, and when the taggers or graffiti writers joined their ranks, it was like driving through street galleries all across the city. In Northeast L.A., the Avenues gang put in serious work in the L.A. River and the Arroyo Seco with their roll calls and panoramic panels. In South Central, the Florencia 13 gang mobbed Florence Avenue with an iron fist, and in Mar Vista and Del Rey, the Culver City 13 boys turned the projects and the Ballona Creek into an outdoor art studio.

Ethnic-influenced murals and gang graffiti were the images that dominated the streets of Los Angeles until the arrival of the New York-inspired, subway wild-style took the region by storm. During the late '80s and '90s, we began to see tagging on a regular basis. Public and private spaces, freeway intersections, street curbs, and other landmarks were the locations of choice. Many legendary taggers wrote in pairs such as: Porno and Phoe, Rock and Akua, Taco and Pyke, Dust and Duel, but it was Chaka who had the most influence across the county until he was caught in 1991. Also, we began to see many tagging and graffiti crews forming and taking the sport to a new level like terrorizing buses, specifically the grills. In the South Bay, the notorious and legendary crew, FSK, vandalized numerous buses daily. New subversive art forms and murals were popping up all over the county, and it marked the beginning of the co-opting process by the establishment. Many businesses commissioned the most prolific writers from legendary crews to ornament their buildings in graffiti wild-style, while the cholo, gang-influenced style and simple street tagging were seen as a culture of waste. Many taggers ended up in prison and joining gangs, while on the streets, the Mexican Mafia ordered taggers to become part of the Sureño culture or turn their crew into a gang.