Many of us have seen Fareed Zakaria on CNN hosting his own program focused on international affairs. His style of journalism and reporting is penetrating, analytical and smacks of an intelligence that seems all too rare on TV these days.

Many of us have seen Fareed Zakaria on CNN hosting his own program focused on international affairs. His style of journalism and reporting is penetrating, analytical and smacks of an intelligence that seems all too rare on TV these days.

In his most recent book, Zakaria, the polymath, turns his attention to a domestic issue. In Defense of a Liberal Education challenges the hawks swooping down on the Liberal Arts in our universities. The predators include, most notably, our current President, Barack Obama, and the numerous states that are turning to performance-based funding of higher education. This financial mechanism provides incentives to schools that, among other metrics, increase the number of students graduating with degrees in "areas of strategic emphasis" like STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics).

For these States, the Liberal Arts are considered an irrelevance. Why do we need degrees in History or Anthropology when what the country really needs to be competitive and successful is technological and scientific skills?

Zakaria is a persuasive advocate for the cause of Liberal Arts. He recounts the history of liberal education from the Greeks to modern times, questions the spiraling costs of contemporary higher education, and endorses the importance, in a truly egalitarian sense, of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). It is worth discussing his arguments and analyses. Indeed, I believe we will all find ourselves at some point fighting for the Liberal Arts either within our Schools or, externally, with accreditation bodies, curriculum designers, regulators and legislators. Zakaria's book has inspired me to add my voice to this cause about which I feel so strongly.

Zakaria is a persuasive advocate for the cause of Liberal Arts. He recounts the history of liberal education from the Greeks to modern times, questions the spiraling costs of contemporary higher education, and endorses the importance, in a truly egalitarian sense, of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). It is worth discussing his arguments and analyses. Indeed, I believe we will all find ourselves at some point fighting for the Liberal Arts either within our Schools or, externally, with accreditation bodies, curriculum designers, regulators and legislators. Zakaria's book has inspired me to add my voice to this cause about which I feel so strongly.

I would like to start with some reflections on a design and innovation firm whose work I have found to be truly fascinating over the last several years, IDEO. This is how IDEO defines design thinking, "To be intuitive, recognize patterns, construct ideas that are emotionally meaningful as well as functional, to express ourselves through means beyond words and symbols. You can't run a company on feelings, intuition and inspiration only, but on the other hand, an overreliance on the rational and analytical can be just as risky. Design thinking is the integrated third way." And then on Education in the C21 the company advocates: "teaching people how to learn, engage and create. The creation of knowledge and the empowerment of individuals to participate, communicate and innovate."

These are powerful statements that articulate a clear symbiosis between the Liberal Arts and business/technological training but without detriment to either. What a contrast to our current world, which increasingly sees education and societal structure in black and white terms, with science, financial skills, engineering, and technology as the keys to our future economic needs. My take on science as part of this mix is to paraphrase Clemenceau, and to say that science is much too important to be left just to scientists. In a similar vein is C.P. Snow's cautionary note about placing too much emphasis on science in education: "So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world would have about as much insight into it as their Neolithic ancestors would have." (C.P. Snow 1959)

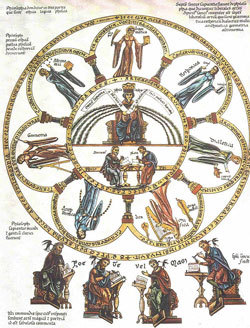

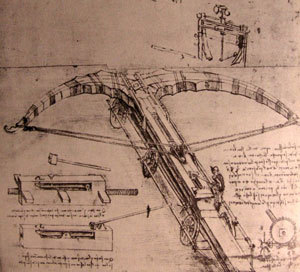

Why this bifurcation between the Sciences and the Liberal Arts when our history from ancient Greek times onwards has consistently demonstrated that both come from the same well of human thought and discovery that IDEO describes as the "integrated third way?" If we go back to the beginning of the Renaissance in the C15 we see a return to humanist thinking based upon intellectual discoveries, curiosity, argument, thought, reflection, philosophy and critical thinking which are the very foundations of the Liberal Arts. And when we look at what was achieved as a result of this rebirth of passion for intellectual creativity from Michelangelo and da Vinci (see his design of large cross bow in photo) to the invention of the printing press and astronomy and the questioning of our place in the universe, it shows the potency of Liberal Arts discovery and thinking.

Why this bifurcation between the Sciences and the Liberal Arts when our history from ancient Greek times onwards has consistently demonstrated that both come from the same well of human thought and discovery that IDEO describes as the "integrated third way?" If we go back to the beginning of the Renaissance in the C15 we see a return to humanist thinking based upon intellectual discoveries, curiosity, argument, thought, reflection, philosophy and critical thinking which are the very foundations of the Liberal Arts. And when we look at what was achieved as a result of this rebirth of passion for intellectual creativity from Michelangelo and da Vinci (see his design of large cross bow in photo) to the invention of the printing press and astronomy and the questioning of our place in the universe, it shows the potency of Liberal Arts discovery and thinking.

- Reading, which provides a pathway into knowledge, self-awareness, critical thinking, curiosity, all touching upon the fundamental questions of the meaning of life.

- Writing, which requires the student to structure his thoughts and arguments in a coherent, logical way.

- Speaking, which arms the student with the confidence and skill to articulate his ideas and arguments in debate and discussion.

- Learning how to learn, which is the basis of continuing education and self-exploration.

To Zakaria's list, I would add Storytelling, which I believe fulfills a basic human need and is the wellspring of our collective consciousness. (Indeed, Zakaria himself is an outstanding example of a great storyteller.)

To demonstrate the critical importance of Liberal Arts-honed skills, Zakaria uses many stories and quotes from the corporate world. He tells of Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, and how he manages his creative team. Bezos insists that his senior management meetings begin with quiet time to allow his executives to read the up to six-page narratives spelling out proposals. "Full sentences are harder to write. They have verbs. The paragraphs have topic sentences. There is no way to write a six -page, narratively structured memo and not have clear thinking." Or there is Steve Jobs (in photo) insisting that "it is in Apple's DNA that technology alone is not enough. It's technology married with Liberal Arts, married with the Humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing." Or Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of Facebook, himself a classical liberal arts student who describes Facebook, one of the most extraordinary inventions of this century, "as much psychology and sociology as it is technology."

To demonstrate the critical importance of Liberal Arts-honed skills, Zakaria uses many stories and quotes from the corporate world. He tells of Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, and how he manages his creative team. Bezos insists that his senior management meetings begin with quiet time to allow his executives to read the up to six-page narratives spelling out proposals. "Full sentences are harder to write. They have verbs. The paragraphs have topic sentences. There is no way to write a six -page, narratively structured memo and not have clear thinking." Or there is Steve Jobs (in photo) insisting that "it is in Apple's DNA that technology alone is not enough. It's technology married with Liberal Arts, married with the Humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing." Or Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of Facebook, himself a classical liberal arts student who describes Facebook, one of the most extraordinary inventions of this century, "as much psychology and sociology as it is technology."

I might extend these conclusions and offer an even more radical recommendation: What if we propose for those in the job market a career path based on what technology and computers can't do well? The machines can without doubt do all the mechanical stuff quicker and more accurately than humans. And for the future we will see many so-called mechanical jobs being automated, such as accountancy, data analysis, information processing, insurance, law and banking. It's happening already after all.

So, where does the individual fit in if he isn't to be the next victim of automation? Technology doesn't do creativity and imagination. We humans do. And we get very stimulated doing just that through the Liberal Arts and the skills they give us. So, for me, we should focus on a whole list of skills and knowledge including languages, economics, history, music, film, writing, designing and entrepreneurship, but with technology as our handmaiden rather than the boss. This argument is already being understood in Europe and Asia. In fact, in Asia, businesses recognize that they are much too technology driven and that they lack the creativity that is the hallmark of American entrepreneurship.

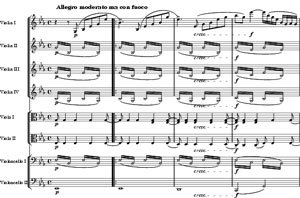

In advocating for the Liberal Arts, I would make a particularly strong case for the study of music. Musicians, far from being too narrowly focused on a marginal subject area, possess the skills that our global world will want and need for the future. This was vividly demonstrated to me during a rehearsal and performance I was involved with as a violinist, of Mendelssohn's Octet. Written in 1825 for four violins, two violas and two cellos, this astonishing masterpiece is the product of a 16-year old composer. It is an amazingly inventive work providing the players and audience a huge amount of joy and fun. It lasts about 30 minutes and it's in four movements all of which are at different speeds and in quite different moods. The players I worked with for this rehearsal and performance were all excellent, had all completed the 10,000 hours that Malcolm Gladwell considers essential for mastery.

In advocating for the Liberal Arts, I would make a particularly strong case for the study of music. Musicians, far from being too narrowly focused on a marginal subject area, possess the skills that our global world will want and need for the future. This was vividly demonstrated to me during a rehearsal and performance I was involved with as a violinist, of Mendelssohn's Octet. Written in 1825 for four violins, two violas and two cellos, this astonishing masterpiece is the product of a 16-year old composer. It is an amazingly inventive work providing the players and audience a huge amount of joy and fun. It lasts about 30 minutes and it's in four movements all of which are at different speeds and in quite different moods. The players I worked with for this rehearsal and performance were all excellent, had all completed the 10,000 hours that Malcolm Gladwell considers essential for mastery.

The actual musical score is complex. It is divided into eight separate lines so it's a bit like being in a room with eight different people speaking all at the same time. The music is technically difficult to play but also very rewarding. The score gives you lots of information about how the composer wants the music performed but it also allows a great deal of flexibility and creativity to the performers. All the parts are important and if you are accompanying a melody it will be up to you to make this magical and special, lifting the melody player to all sorts of new heights of expression. To bring all this off is an exercise in some of the most intensive forms of communication and collaboration you could come across.

To begin with, communication works on a number of fronts. It can be observational, intuitive, and non-verbal. In other words a type of "telepathy" exists based purely upon listening and watching. Eyes are very important. Verbal communication and discussion are used as well during rehearsal, but within a performance, it is pretty much all non-verbal. Then there is consensus building within the group. How to decide through the various types of communication how something might go or how a problem can be resolved. The psychology of the group is as complex as the number of players and personalities. For each individual, there is analysis of the score and one's own part in it, individual practice, managing one's vulnerability, and working toward product improvement, all in the interest of making the performance as good as you can. Team building, leadership, mutual respect, dealing with challenges, focus, hard work, and sheer unadulterated creative magic bring the music to life. Now given all these skills and characteristics, what creative business would not want a musician as part of the team!? What's more, you could never, ever have a computer come close to replicating this.

Zakaria is a compelling spokesman for the Liberal Arts. He shows unequivocally their importance in the cultural, economic and developmental world and how our world becomes threatened by the narrow focus of Manichean politics. He reminds us that we need all the many kinds of knowledge, or "the reunion of broken parts" which is the translation of the Arabic word "algebra." The alternative title to this blog plays on that connection. If our world is becoming fragmented in terms of our values then we should consider this reunion, the creation of the integrated third way, which allows value and importance to be granted to all our thinking.