Two years ago, the Pew Research Center released a monumental study in which it was revealed that, over the past decade, the mean family income in the United States decreased for the first time since the second World War. "Since 2000," the report read, "the middle class has shrunk in size, fallen backward in income and wealth, and shed some -- but by no means all -- of its characteristic faith in the future."

North Carolina's middle class had been aware of this trend for quite some time, particularly since the state economy's transition from a reliance on the manufacturing sector to a reliance on the service sector divided the middle class into a lower class of workers, who are caught in the low-wage service sector due to their lack of certain educational and training experiences, and an upper class of workers, whose extensive education and training afford them access to high-wage employment opportunities.

As if this was not bad enough, the Republican-majority General Assembly's recent decisions to shift the tax burden to the lower and middle classes, repeal the earned income tax credit and reduce the length and maximum amount of unemployment benefit provisions deepen this economic divide.

The resultant economic inequality between the lower and upper classes impairs the state's economic development, particularly because it decreases economic mobility, discourages entrepreneurship, results in poor educational outcomes, shortens economic expansions, lengthens economic contractions, increases pessimism, threatens social cohesion and undermines faith in our system of democracy.

In order to address the state's economic inequality, policy leaders ought to adopt an integrated, "all-of-the-above" approach to economic development, which entails the promotion of family income growth, the creation of new employment opportunities that pay high wages and the assurance of economic mobility through the creation of pathways from low-wage employment to high-wage employment.

But even then, it remains unknown whether North Carolina's middle class will develop to the extent that it did many years ago.

The State's Manufacturing Economy and the Growth of the Middle Class

Nearly a century ago, North Carolina's economy was significantly different than those of its neighbors. The Civil War did not impact the state's economy the way it impacted those of other southern states and, in contrast to the rest of the South, North Carolina was advantaged in the resources necessary to venture into new industries, particularly those of textiles, tobacco and furniture.

The Piedmont's bountiful waterpower and acreage were necessary for textile production, but most important, wrote former N.C. Insight editor Bill Finger, "was the abundant labor supply, mainly yeomen farmers working war-ravaged land." Soon enough, the state's population shifted from the Mountain Region to the Piedmont as cotton farmers discovered a new and emerging market close to home. From 1923 to 1933, New England lost nearly 40 percent of its cotton mills, and the South's industry grew significantly. North Carolina soon became home to Burlington Industries, the world's largest textile company. "Nowhere did growth accumulate more rapidly," wrote Finger, "than in North Carolina."

Textiles were not the only source of economic development in the state, as tobacco similarly began to gain prominence at the turn of the twentieth century. By the turn of the century, Durham native James Buchanan Duke, who had acquired a license to use the first automated cigarette making machine, supplied nearly 40 percent of the American cigarette market. His competitor, R.J. Reynolds, would eventually develop his Winston-Salem-based R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company into the second-largest tobacco company in the United States. Soon enough, North Carolina ranked first in the nation in the production of tobacco.

Though North Carolina was home to only six furniture plants -- in Goldsboro, Charlotte, Mebane, Ramseur, Lenoir and Asheville -- its Piedmont and Mountain Region provided the expansive hardwood forests necessary for the furniture industry to prosper. After the culmination of World War II, homebuilding across the nation increased 300 percent, and manufacturers from all across the country traveled to the state's furniture exposition in High Point. The $5 billion in revenue that the city accumulated after the war forecast significant economic growth for the state. In due time, North Carolina became home to "The Furniture Capitol of the World."

"From 1900 to 1939, the state increased its value of manufactured products 1,397 percent," wrote Finger, "far more than any other Southern state except Texas, a close second." North Carolina's investment in the textile, tobacco and furniture industries provided countless low-skilled workers with the opportunity to earn decent wages and established a strong foundation for the state's middle class.

The Transition to a Service Economy and the Division of the Middle Class

All changed when the state's economy paralleled the national economy in its transition from a reliance on manufacturing to a reliance on services.

Writes the North Carolina Budget and Tax Center's Allan Freyer:

As a result, thousands of low-skilled jobs that provided a critically important ladder out of poverty and into the middle class for three generations of North Carolinians have disappeared and been replaced with jobs in hospitality, retail services and other services that pay much less.

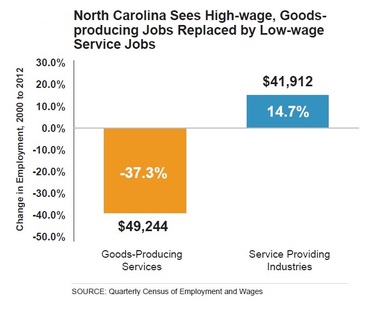

While the waning manufacturing sector offers low-skilled workers employment that guarantees incomes at, or higher than, the state's median household income of $45,570, the growing service sector guarantees quite the opposite. Since 2000, employment in the manufacturing sector -- which pays, on average, around $49,000 annually -- decreased by nearly 37 percent, a number significantly higher than the national average and that of any neighboring state. On the other hand, employment in the service sector -- which pays, on average, an annual salary of $42,000 -- increased by almost 15 percent.

Eight of the state's 10 industries with the greatest amount of job losses are in the manufacturing sector, and seven of those industries pay more than the state's median wage earnings of $31,900 annually.  The fasting growing industry in the state, which happens to be in the service sector, pays significantly less than the state's median wage earnings. In fact, it pays $14,350 annually.

The fasting growing industry in the state, which happens to be in the service sector, pays significantly less than the state's median wage earnings. In fact, it pays $14,350 annually.

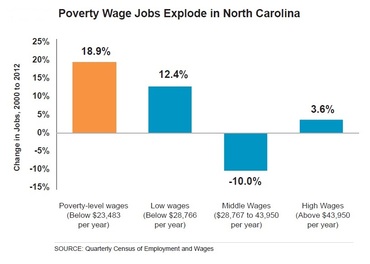

The state economy's transition -- the replacement of low-skilled jobs that offer decent wages with low-skilled jobs that offer wages less than the state average -- bears its brunt on the lower and middle classes. The number of low-skilled jobs which pay less than $23,484 in annual wages has increased by 19 percent, and the number of low-skilled jobs which pay between $28,787 and $43,950 in annual wages has decreased by 10 percent.  The amount of high-skilled jobs which pay more than $43,950 in annual wages, on the other hand, has increased by four percent. The requirements necessary to attain a high-skilled job, such as completing post-secondary education or undergoing extensive training programs, are substantial obstacles for less-skilled workers who desire to earn higher wages, especially in North Carolina, where reduced funding for public institutions of higher education and training programs have resulted in higher costs of attendance and completion.

The amount of high-skilled jobs which pay more than $43,950 in annual wages, on the other hand, has increased by four percent. The requirements necessary to attain a high-skilled job, such as completing post-secondary education or undergoing extensive training programs, are substantial obstacles for less-skilled workers who desire to earn higher wages, especially in North Carolina, where reduced funding for public institutions of higher education and training programs have resulted in higher costs of attendance and completion.

North Carolina's middle class, once a unique amalgamation of low-skilled and high-skilled workers earning decent wages in the manufacturing sector, has been split into a low-skilled lower class, which is unable to escape the dwindling wages of the service sector, and a high-skilled upper class, which is savoring the bountiful opportunities offered by the state economy's recent transition.

Deepening the Inequalities

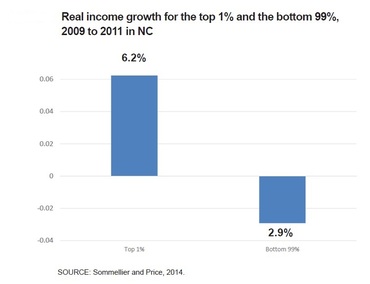

This has resulted in the effective elimination of the state's middle class and a deepening of economic inequality between the lower and upper classes. Though such may be the case in other states, North Carolina's situation appears to be worse.  In the years following the Great Recession, the top one percent saw their incomes increase by 6.2 percent, while the bottom 99 percent saw their incomes decrease by nearly 3 percent. North Carolina is one of only 17 states that have experienced income growth for the top one percent and income depreciation for the bottom 99 percent since the Great Recession. In addition, the average income of the bottom 99 percent of North Carolinians is $39, 145, well below that of the South and the rest of the nation.

In the years following the Great Recession, the top one percent saw their incomes increase by 6.2 percent, while the bottom 99 percent saw their incomes decrease by nearly 3 percent. North Carolina is one of only 17 states that have experienced income growth for the top one percent and income depreciation for the bottom 99 percent since the Great Recession. In addition, the average income of the bottom 99 percent of North Carolinians is $39, 145, well below that of the South and the rest of the nation.

If the effects of the state economy's recent transition did not deepen the divide between the classes, the General Assembly made sure to take up the slack.

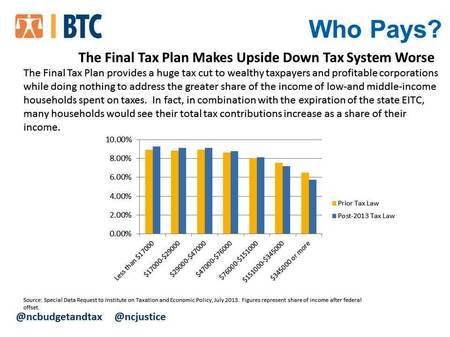

The state's progressive personal and corporate income taxes were recently lowered and flattened, while the estate tax was repealed and the sales tax expanded to encompass currently untaxed items. The General Assembly's own Fiscal Research Division recently found that a married couple with two children making $20,000 a year will go from receiving a $222 tax rebate to owing $40 while a similar couple making $250,000 a year will receive a $2,318 tax cut.  When considering the repeal of the earned income tax credit -- which financially assists 907,000 low-income workers and ensures that 298,000 of them remain out of poverty, the net effect is an increase in taxes for over 80 percent of North Carolinians, including everyone who makes between $17,000 and $151,000 annually. A recent study conducted by economists from Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley finds that states with lower income taxes, particularly on the wealthy, experience less economic mobility. Additionally, these tax policy changes will reduce the state's revenue by more than $2 billion in the next five years, an effect which will likely impact public services in the future.

When considering the repeal of the earned income tax credit -- which financially assists 907,000 low-income workers and ensures that 298,000 of them remain out of poverty, the net effect is an increase in taxes for over 80 percent of North Carolinians, including everyone who makes between $17,000 and $151,000 annually. A recent study conducted by economists from Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley finds that states with lower income taxes, particularly on the wealthy, experience less economic mobility. Additionally, these tax policy changes will reduce the state's revenue by more than $2 billion in the next five years, an effect which will likely impact public services in the future.

In addition, the reduction of the length of unemployment benefit provision from 26 weeks to a sliding scale of 12 to 20 weeks, the reduction of the maximum unemployment benefit provision from $535 to $350 per week and the elimination of benefits for workers who accept a family or medical leave of absence will result in the denial of benefits to nearly 170,000 unemployed citizens and, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Patrick Conway, inhibit the prevention of nearly 50,000 North Carolinians from falling into poverty on an annual basis.

The shifting of the tax burden from the upper class to the lower and middle classes, the repeal of the earned income tax credit and the reduction of the length and maximum amount of unemployment benefit provisions ensure the gradual erosion of the middle class and the increasing division between the lower and upper classes.

But what is so bad about economic inequality?

After all, it could be the case that the state's Republican-majority General Assembly espouses the same viewpoint as Minnesota State Senate Minority Leader David Hann, who is "not so sure, not persuaded by [the] data, that [economic inequality] is a bad thing."

The Effects of Economic Inequality

There has been much discourse and research into the negative effects of economic inequality. Among the most important of these findings, according to The Center for American Progress, is "that a trade-off exists between high and growing levels of inequality," particularly income inequality, "and economic growth." This is due to a variety of reasons:

Firstly, the National Bureau of Economics recently found that an increase in income inequality is correlated with a decrease in economic mobility. Since income inequality is growing in North Carolina -- primarily due to the state economy's transition from a reliance on the manufacturing sector to a reliance on the service sector and partly due to the recently enacted policies of the General Assembly -- the probability that an offspring earns an income within the top quintile of the national income distribution when his or her family's income is within the bottom quintile is 4.4 percent in Charlotte, North Carolina but 12.9 percent in San Jose, California. Ben Olinsky and Sasha Post of The Center for American Progress recently wrote:

If you were born around 1980 and raised in a lower-income family in Raleigh, chances are you're not making much more now than your parents did when you were growing up. But if Raleigh's middle class were as large as the average city's, you'd be earning nearly $5,500 more a year than you do now.

Secondly, the North Carolina Budget and Tax Center recently cited research indicating that income inequality considerably discourages entrepreneurial undertakings and inhibits individuals from seeking different employment opportunities they are better suited for later in their careers. This is particularly relevant in North Carolina, where financial security, according to the Center for Corporation for Enterprise Development, ranks 46th in the nation. More than half of North Carolinians do not have the financial resources necessary to withstand unexpected situations including, but not limited to, loss of employment or a medical emergency.

Thirdly, a report published by The Center for American Progress verified a significant relationship between an increase in income inequality and poor educational outcomes, particularly because lower class families are unable to afford investments in their children's educations.

Fourthly, in its analysis of 174 countries, the International Monetary Fund demonstrated that "countries with more equal income distributions tend to have significantly longer growth spells," or longer periods of economic growth. Countries with less income inequality have experienced longer economic expansions and shorter economic contractions.

Finally, Eric Uslaner, a professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland at College Park, found that income inequality results in increasing pessimism, threatens social cohesion and undermines faith in our system of democracy. "The public has become less optimistic about economic growth, more pessimistic about the welfare of the average person, and less trusting of other people, as income inequality has skyrocketed over the past 30 years," summarizes The Center for American Progress' Nick Bunker.

So, what is there to be done?

An Economy that Works for All

Allan Freyer, a policy analyst at the North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, recently wrote that, in order to address the state's economic inequality, policy leaders ought to adopt an integrated, "all-of-the-above" approach to economic development. Such an approach entails the promotion of family income growth, the creation of new employment opportunities which pay high wages and the assurance of economic mobility through the creation of pathways from low-wage employment to high-wage employment.

The promotion of family income growth requires the state government to target employment opportunities which pay at, or above, the average living income standard, a measure of the amount of money required for North Carolina families to afford basic necessities. Rather than target leisure and hospitality employment opportunities, both of which pay significantly less than the average living income standard, the state government ought to target higher-wage employment opportunities including, but not limited to, medical device manufacturing and pharmaceuticals. Such opportunities ensure a much-needed increase in family incomes.

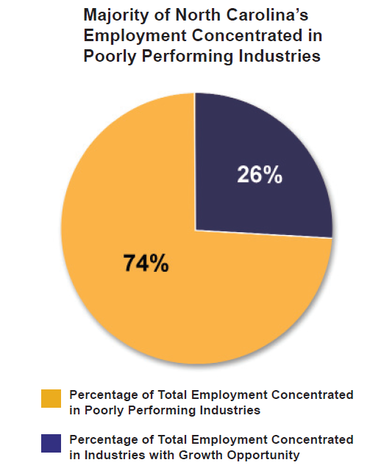

In order to create new employment opportunities which pay high wages, the state government ought to stimulate the growth of stable industries that are competitive and best poised for future expansion. Currently, 74 percent of the state's workforce is concentrated in unstable industries that are either declining, such as the manufacturing industry, or performing poorly in comparison to those of other states, such as the service industry.  Only 26 percent of the state's workforce is concentrated in industries that are expanding or effectively competing with those of other states. These industries, which encompass electronic instrument manufacturing, data processing and chemical preparation manufacturing, ought to become key investments in the future.

Only 26 percent of the state's workforce is concentrated in industries that are expanding or effectively competing with those of other states. These industries, which encompass electronic instrument manufacturing, data processing and chemical preparation manufacturing, ought to become key investments in the future.

Lastly, the state government ought to invest in career pathways programs to guarantee that low-income workers have an opportunity to better their skill-set and earn increasingly higher incomes over time.

"Career pathways," writes Freyer, "involve a series of connected training programs and student support services--often designed as a series of academic or professional credentials offered through local community colleges--that enable an individual to gain progressively more advanced job training and greater skill development in specifically targeted high-demand industries."

For instance, the BioNetwork, a network of local community colleges which provide workforce development to life science firms, has worked with the North Carolina Department of Commerce and the North Carolina Biotechnology Center to increase the skill-set of the state biomanufacturing industry's workforce, thereby contributing to the earning of higher wages within the industry. Such relationships, which ensure economic mobility through the betterment of skill-sets and the creation of pathways from low-wage employment to high-wage employment, will help in lessening the divide between the lower and upper classes and restoring the middle class.

Just Ask North Carolina

The New York Times recently ran an article in its Business section titled, "The Middle Class Is Steadily Eroding. Just Ask the Business World."

Considering the state economy's transition from a reliance on manufacturing to a reliance on services, the division of the middle class into a permanent lower class and a permanent upper class and the Republican-majority General Assembly's recent policy decisions, Nelson Schwartz ought to issue a correction of his article's title:

"The Middle Class is Steadily Eroding. Just Ask North Carolina."

Much remains to be done with regard to restoring the middle class, and even if the state government implements policies to promote family income growth, the creation of new employment opportunities and the assurance of economic mobility evenly across the state, North Carolina will possibly never again see the day in which its middle class flourishes.