Given the recent severe drought -- and intense rains -- it's worth considering which plants do well in northeast Illinois and why.

When European settlers made their way from the east to Illinois, emerging out of the hardwood forests of Appalachia into the tallgrass prairie of the heartland, they were astonished, disbelieving. The land that was to become the Chicago region was a tapestry of rolling savanna and prairie, clear streams and noble groves of ancient oaks. Buffalo, cranes, turkeys, beaver, mountain lions all made their home here. Vast beds of mussels and clams were found.

The Chicago region happens to lie where three major biomes converge. We are situated at the southernmost extent of the north woods from Wisconsin; we are at the eastern extent of the tallgrass prairie, and we are at the western edge of the eastern hardwoods from Appalachia. And wherever you have these major biomes converging, you get enormously rich biological diversity as a result. So, for instance, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, which is fairly small as national parks go, has the third most plant species of any national park and more than the island of Great Britain.

The rich black soil was recognized soon enough as the permanent foundation of a Midwestern economy, and a great metropolis would grow here. Indeed, one historical fact worth noting is that Chicago is the largest city in the country whose name links it to the native landscape. For Che-ca-gou was the Native American name for the wild onions that grew in profusion along the riverbanks and swampy areas when Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet paddled their canoe into these waters in 1673.

Marquette wrote in his journal: "We have seen nothing like this river that we enter, as regards its fertility of soil, its prairies and woods, its cattle, elk, deer, wildcats, bustards, swans, ducks, parroquets, and even beaver. There are many small lakes and rivers. That on which we sailed is wide, deep, and still, for 65 leagues. In the spring and during part of the summer there is only one portage of half a league."

Settlers coming west in the mid-1800s rode through the oak groves, kept open by periodic fires set by lightning or by Native Americans, and made their way across a sea of grass. "From the first oak openings of Ohio and Kentucky till it washed to the foot of the Rockies, grass ocean filled the space under the sky," wrote naturalist Donald Culross Peattie. "Steppe meadow, buffalo country, wide wilderness, where a man could call and call but there was nothing to send back but an echo."

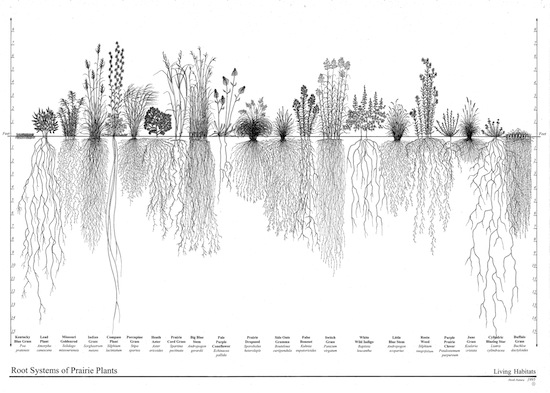

Peattie has called the deep root systems of native prairie plants, the "empire of locked roots...Root touched root across this empire," he wrote. Those roots of native prairie plants, some stretching 10-to-15 feet belowground -- shown here in a wonderful illustration by Heidi Natura -- are a carbon capture system and a water capture system. In contrast, the roots of Kentucky bluegrass that now carpets our lawns and corporate campuses extend about three inches down (the small smudge on the far left of the illustration).

The plows the settlers brought with them from the East could not break the tough prairie soils, the "empire of locked roots." It was not until a blacksmith named John Deere in McHenry County (and another named John Lane in Will County) invented a steel moldboard plow that settlers could 'break' this tough prairie soil and the empire began to fall. Once this new plow demonstrated its effectiveness, within the space of a generation we had transformed the landscape, converting the prairies into Illinois' rich agricultural base.

The benefits were enormous -- but so, it turns out, were the costs. We have lost much of our native biological diversity, and the ability of the ecosystem to capture water and carbon.

There is a wisdom in these native plants, a wisdom reached over thousands of years evolving in this climate, in these soils. Come to think of it, prairie plants don't need to be mowed or watered! Given the drought we are experiencing now in Illinois, should we consider the merits of the carbon and water capture system that native plants provide, a pathway for water to recharge our aquifers, a repository for carbon from the atmosphere?

Go ahead. Liberate a part of your lawn. The birds, the bees, the butterflies and beneficial insects, and your wallet will thank you.