In the early days, every public official associated with TARP--the $700 billion Targeted Asset Relief Program--promised openness and transparency.

"We need oversight," Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson declared on September 23 to the Senate Banking Committee. "We need protection. We need transparency. I want it. We all want it." The next day, at a joint House-Senate hearing, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke backed Paulson up: "Transparency is a big issue." Less than a month later, on October 13, newly appointed Assistant Treasury Secretary for Financial Stability Neel Kashkari told the Institute of International Bankers:

"Treasury is committed to an open and transparent program with appropriate oversight. We look forward to continuing to work with the Oversight Board, the Inspector General, the Comptroller General, and the Congress as we set up and execute this program. Transparency will not only give the American people comfort in our execution, it will give the markets confidence in what form our action will take."

Since then, all fees and hourly rate charges have been blacked out on publicly-available copies of Treasury oversight and financial management contracts with law firms, banks and other consultants; banks receiving billions of dollars in taxpayer money have stonewalled press inquires about what they have done with the cash; key government boards make policy behind closed doors and release minutes that only hint at the problems the massive program has encountered; and at least three news organization - Bloomberg, Fox News and Bailoutsleuth.com -- have filed suit to force disclosure of more key information.

Brookly McLaughlin, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, defended practices at Treasury, saying "there are several reporting requirements and we have met every one of them."

The opaque character of much of TARP is reflected in the proceedings of the five-member Financial Stability Oversight Board (FSOB), which has responsibility for reviewing the program and evaluating its effectiveness "in assisting American families in preserving home ownership, stabilizing financial markets, and protecting taxpayers." FSOP members are Bernanke, chair; Paulson; Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) chair, Christopher Cox; Director of the Federal Housing Financing Agency (FHFA), James B. Lockhart III; and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Steve Preston.

The FSOB held a closed meeting on December 10 to discuss an extraordinary range of key economic and policy issues. Later, tor public consumption, the board released four pages of minutes.

For those curious about what this group of five top policy-makers was up to, there are a grand total of 928 words describing their take on such complex matters as the overall effectiveness of TARP; the massive $55 billion Treasury purchase of Citibank preferred stock, along with "the loss protection and residual financing" on $306 billion in assets provided to Citigroup by Treasury, the FDIC and Federal Reserve; the procedures governing public access to records; the state of the housing and financial markets; the need to establish "metrics" to evaluate TARP; and the development of a strategy for ultimately unloading all assets acquired under TARP

If these issues were dealt with in a substantive manner, you would never know it by reading the minutes.

A total of 117 words are devoted to subsidies for Citigroup, and the reader of the minutes learns only that the FSOB "discussed the package of governmental supports," "discussed the terms and structure," and "discussed the manner in which the investment and guarantee by Treasury would be structured."

Jason A. Gonzalez, FSOB secretary, might qualify for nomination to the bureaucratic hall of fame - he uses the words "discussed" or "discussion" 20 times -- except for one slip-up: toward the end of the document, Gonzalez writes something that actually reveals something, albeit modestly:

"Members also discussed the difficulty of isolating the effects of the TARP given the variety of policy actions taken by the U.S. government to support financial stability and promote economic growth and the short time that has elapsed since the TARP was first implemented, and the difficulties associated with monitoring the use of specific funds by individual institutions."

In other words, even the top guns in federal finance are having difficulty figuring out whether the billions and billions they are handing out are actually doing any good, and they have run head on into "difficulties" when trying to look at how an individual bank makes use of its infusion of cash.

It would appear that the FSOB is getting the same run-around as the Associated Press.

The AP contacted 21 banks that have each received at least $1 billion and all of the banks refused to give specific answers to four questions: "How much has been spent? What was it spent on? How much is being held in savings, and what's the plan for the rest?"

"We're choosing not to disclose that," Kevin Heine, spokesman for Bank of New York Mellon, told the news service. The New York Mellon bank not only received $3 billion on October 28, but Treasury has hired the bank to served as an overseer of TARP, "to provide the accounting of record for the portfolio, hold all cash and assets in the portfolio, provide for pricing and asset valuation services and assist with other related services."

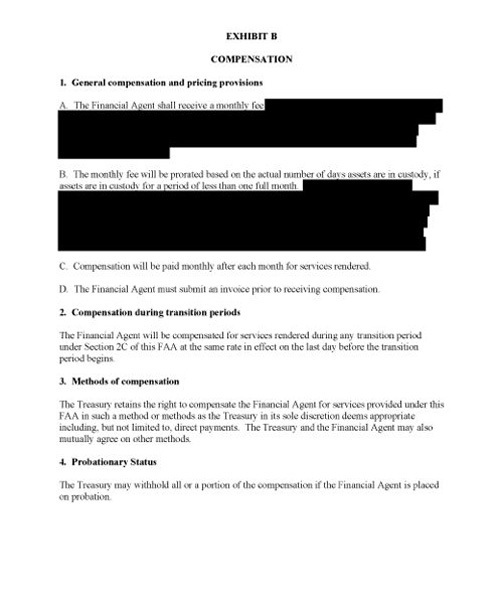

It is, however, difficult to figure out how much New York Mellon will get paid for these services. The contract, posted on Treasury's web site, shows the following:

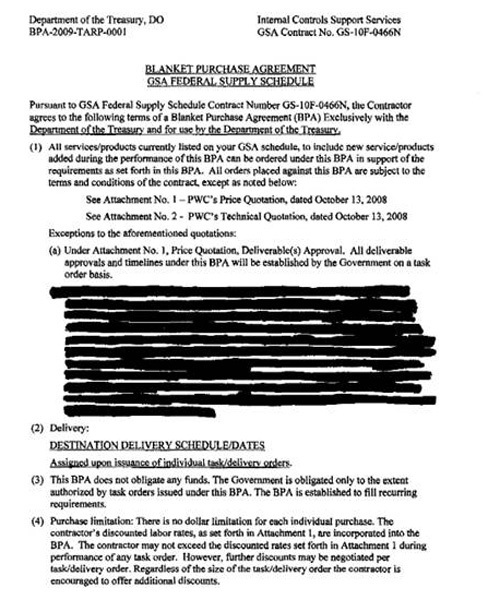

The blackout of compensation details is repeated over and over again in Treasury contracts, as Chris Carney of bailoutsleuth.com points out. A contract with PriceWaterhouseCoopers LLP has the following page:

Treasury's McLaughlin contends that this kind of information is blacked out for "business proprietary reasons;" that the disclosure of firm A's fee structure would "hurt its ability to compete" against other companies; and that other companies would know how firm A calculates costs.

In addition to the reluctance of Treasury and the FSOB to be transparent, the Federal Reserve has come under fire for its refusal to identify specific banks that have obtained roughly $2 trillion in emergency loans. Bloomberg.com has filed suit http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aatlky_cH.tY&refer=worldwide under the Freedom of Information Act seeking this data. Bernanke defended the practice at a Nov. 18, 2008 House Financial Services Committee hearing:

"The Federal Reserve, like all other central banks, has short-term, collateralized lending programs to financial institutions.... Now, some have asked us to reveal the names of the banks that are borrowing, how much they're borrowing, what collateral they're posting. We think that's counterproductive because -- for two reasons. First, the success of this depends on banks being willing to come and borrow when they need short-term cash. There's a concern that if the name is put in the newspaper that such and such bank came to the Fed to borrow overnight for a good reason, that other might begin to worry is this bank credit worthy. And that might create a stigma, a problem, and might cause banks to be unwilling to borrow. And that would be counterproductive for the whole -- the whole purpose."

While transparency is almost universally praised, even in the breach, one of the strongest arguments used both for and against full disclosure is that it increases the likelihood that the public will learn how little confidence public officials really have in their own judgment: The minutes of the FSOB cited above -- "Members and officials discussed, among other things, the current financial health of large financial institutions" -- are certain to mask the kind of conflicting opinions, doubts and anxieties that top federal officials are loath to reveal in public.

More importantly, a more detailed record of the decision-making process would reveal the thinking behind some questionable, or bad, decisions. Early on in the financial crisis, Paulson, Bernanke and others made choices to save some private institutions, to devalue others and, in the case of Lehman Brothers, to allow a major Wall Street company to go belly up.

Since then, there has been considerable debate over the consequences of the Lehman decision, and it is doubtful that anyone wants to take full responsibility. On September 15, the day Lehman filed for bankruptcy, the Dow dropped 504.48 points, accelerating the economic collapse and making banks increasingly unwilling to lend and to revive economic activity. There is no way to put a dollar figure on those costs, but they were -- and are -- enormous.

In late December, nearly two and a half months after the collapse of Lehman, the firm overseeing the restructuring of the firm, Alvarez & Marsal, estimated that as much as $75 billion had been destroyed, in the words of the Wall Street Journal, "by the unplanned and chaotic form of the firm's bankruptcy filing."

"While I have no position on whether or not the federal government should have provided further assistance to Lehman, once the decision was made not to provide further assistance, an orderly wind-down plan should have been pursued. It was an unconscionable waste of value," Bryan Marsal, Alvarez & Marsal co-CEO, said.

The WSJ story about Lehman's chaotic bankruptcy filing was buried inside the A section on the bottom of the page, but it is very doubtful that the participants in the decision to allow Lehman to fail would want full transparency - a transcript or, better yet, a video - of what they said during the closed meetings and discussions about the future of Lehman.

The reality, however, is that in the world of banking and finance, transparency is an alien concept; that deals, including those involving the federal government, are generally conducted behind closed doors, or at least behind a curtain. In an interesting twist, the Federal Reserve's own "Guide to Meetings of the Board of Governors" carries the headline "Government in the Sunshine," but the most important section of the guide details the governing of closed meetings. It is in private sessions that the Federal Reserve Board takes on the real bread and butter issues of "bank and bank holding company supervisory matters" and "monetary policy and other matters whose premature release could be used in financial speculation."

If the Fed conducts business by these rules, how can private banks be expected to open their deliberations - even those involving taxpayer dollars -- to the public?