This is the next in a series of interviews with individuals working in the field of anti-trafficking. You'll meet students and educators, parents and professionals whose voices may give readers a new and better understanding of this crime while teaching us how to respond more effectively to it.

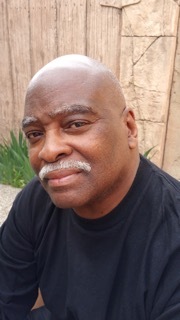

Lt. Andre Dawson, Los Angeles Police Department (Retired), Officer in Charge, Human Trafficking Unit, served 33 years in law enforcement including six years supervising the daily operations of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Human Trafficking Task Force and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Child Exploitation Task Force.

Robert: How has policing, as it relates to CSEC (Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children), changed since you came on to the force?

Lt. Dawson: The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) changed the landscape of how we investigate and prosecute CSEC cases. Pimping, pandering and prostitution are certainly not new to police and prosecutors. What is new are the dynamics that TVPA brought to the understanding of CSEC and the circumstances surrounding their exploitation.

Robert: I know you've supervised many child sexual exploitation cases over the years and I'm sure no two are exactly alike. Can you describe one case that best represents the challenges faced by families, law enforcement and communities in addressing this dilemma?

Lt. Dawson: A case went to trial involving a female minor victim. Let's say her name was, Katrina. She had been sexually exploited by her pimp. Katrina explained to officers the horrible abuse she had endured. By the time she gave her testimony in court, however, the story had changed. This is an example of how sexually exploited children, when brought forth to testify against their abusers, can become very protective instead. Katrina still felt very loyal despite how badly she was treated.

Allegiance and/or love for an abuser, who is in the courtroom facing the victim, is only one reason for inaccurate testimonies. S/he may also be afraid of the pimp or trafficker due to previous acts of violence, the victim's Trauma Bond or because of symptoms of Stockholm Syndrome. Pimps rely on threats of physical violence and/or intimidation to avoid being prosecuted. Whether or not a victim cooperates, however, s/he should still receive the needed services.

The victim's mindset should be considered during the investigation and prosecution of a case as well as the entire context of exploitation. These are very complex cases. It's been my experience that a positive working relationship between investigators and prosecutors is one of many key factors to successfully prosecuting CSEC cases. And, even when a victim does testify, justice is not guaranteed. Overwhelming evidence is sometimes introduced in court - describing the actions of a pimp and how he tried to prevent the victim from cooperating with law enforcement - yet the jury will find the pimp not guilty of human trafficking related charges that potentially could have sent him to prison for life. It's difficult for a jury to truly comprehend the violence, forced drug use, psychological manipulation and constant physical threats that are so prevalent in these cases.

Education, awareness and empathy are critical in making any informed decision involving sexually exploited human beings. It's important to keep in mind, even when law enforcement rescues a child from exploitation, they are faced with the challenge of keeping the victim safe and identifying appropriate resources. Unfortunately, there is a desperate lack of safe residential housing as well as mental and medical aftercare for victims.

Robert: What, in your opinion, is the greatest barrier to helping sexually exploited children?

Lt. Dawson: Terminology is a big problem. We must stop identifying sexually exploited children as prostitutes. Calling a child "prostitute" suggests that s/he is selling his or her body by choice. Modern day sex slavery is not a choice.

State, federal and international law says that a child cannot consent to commercial sex. A "child prostitute" does not exist. When you call a sexually exploited child a prostitute, you lose opportunities to assist that child in any meaningful way. Beyond terminology, we also have to change how sexually exploited children are treated within the criminal justice system. These are victims not criminal suspects. And, in jurisdictions where children may be treated as criminal suspects, then victim services are not available to them.

Robert: What can parents do to protect their children from the threat of trafficking?

Lt. Dawson: Understand that this response is not all-inclusive. Be proactive in your children's lives. Pay particular attention to their social media. There used to be a time when parents talked to their children and educated them about being aware of strangers. Today, social media is awash with strangers.

Be aware of behavioral changes that may be caused by drugs. Recognize new clothing that is not age appropriate. Look for electronic devices that do not belong to your children. And monitor your children's friends who may influence unusual activities and/or behavior. Trust your instincts, if you feel something is wrong, you're probably right. Don't be afraid to ask questions.

Robert: Is there a way to end human trafficking? If so, how?

Lt. Dawson: I do believe we can end human trafficking or make significant progress in doing so, but it requires a collaborative effort between stakeholders, educators, policy/law makers, law enforcement, prosecutors, social care providers, community and faith based groups. Stakeholders that have a vested interest in ending human trafficking must provide the appropriate funding for the most desperately needed safe housing, medical treatment, mental resources, education, family counseling and police resources.

For the past six years, I have been on the reactive side of human trafficking, rescuing sexually exploited human beings and arresting those responsible. By the time law enforcement rescues a sexually exploited child, significant mental and physical damage has already been done. Since I've retired, I have started looking at human trafficking through the proactive lens of "prevention through education." Placing a specific focus on educating our children and explaining the consequences of such destructive behavior is a step in the right direction and a very effective strategy.

Robert: Thank you, Lt. Dawson!