"Twelve, thirteen, fourteen, there's another one over to the left." He can see them better than I can. Ellsworth Kelly's electric blue eyes are registering an accurate headcount of the distant poults trailing three mature turkeys across the grounds of his Spencertown, NY home. We are outdoors, observing an artist's copy of his tall steel "Berlin Totem," installed at the U.S. Embassy in Germany. He suggests I examine it from a different perspective. "If you can eyeball it from the curve up and look up straight, doesn't it look strange?" It does. It looks like it is curving over my head, which it is not.

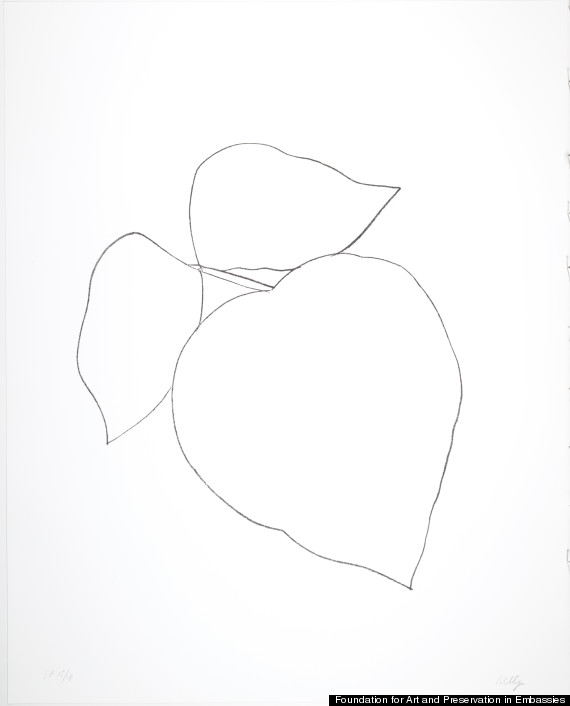

Ellsworth Kelly, Leaves, 1997, transfer lithograph, 36 1/2 x 29 1/2 inches. Gift of the artist and Gemini G.E.L.

Ellsworth Kelly, who turns ninety on Friday, May 31, is all about seeing. He has always looked at objects differently than anyone else. When others admired paintings at Musee d'Art Moderne in Paris, the young American veteran of World War II chose to be inspired by the museum's windows. The striped mending patches on beach cabanas provided another source for the revolutionary abstractions he extracted from quotidian shapes. He says, "I wanted to make something I hadn't seen yet." After six years in France, selling only a single painting, Kelly arrived in New York in 1954 and soon achieved renown for his monochromatic curved canvases and pulsating panels. Kelly is still wildly productive, his work seemingly imbued with both poetry and mathematics. I had witnessed his new reliefs at Matthew Marks Gallery, shaped canvases overlapping rectangular bases. This year, he is working with metallic paint for the first time.

And in his handsome barn-like multi-roomed studio in the Hudson River Valley, he presents a newly completed piece, a relief of yellow canvas partially obliterating white. He explains, "Traditional painting, up to now and still happening, has a theory of form and ground sharing the same canvas. If this yellow curve were painted on the same canvas as the white, the yellow being the form because it is about the yellow shape, and the ground would be the white part of the canvas. But in this painting the yellow panel is fastened on top of the white panel, a 'real' relief; as an object. Therefore, the painting itself is the 'form' and the 'ground' is the wall it is hung on." The shadows from the yellow relief seem to add a third color to the artwork.

In a 1950 letter to his friend, the composer John Cage, Kelly wrote, "To hell with pictures-they should be on the wall-even better-on the outside wall-of large buildings." His recently unveiled 'Beijing Panels' perfectly coordinate with these sixty-year-old words. The fraternal twin reliefs on the exterior walls of the U.S. Embassy in China consist of an 18 foot red, white and blue aluminum wall sculpture, greeting visitors, and another 18 footer, in red and yellow, bidding the departees farewell.

Kelly donated his massive striking sculptures to the US Embassies in both Berlin and Beijing. The fabrication, transportation and installation were funded by FAPE, the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies, a unique and laudable private organization providing stellar contemporary artworks to American embassies.

Interspersed with his abstract work, Ellsworth Kelly continuously draws flora. He has also donated several of these elegant drawings to FAPE, including "Magnolia", "Orange Tree" and "Milkweed". His transfer lithograph, "Leaves" has been disseminated to fifty embassies.

The artist says, "All my work begins with drawings. I don't labor over my drawings. I want to get freedom in the line. I like to be able to get swift curves in the plant drawings that are usually drawn in five to ten minutes." A lofty space holds brilliantly colored shaped canvases, varying layers of flawless oil paint drying. I am startled by several large pieces, clearly shaped like Ellsworth Kelly sculptures and reliefs, but these are wood: mahogany, redwood, birch. They were exhibited in Boston last year at the Museum of Fine Arts, where Kelly had been a student after the war, supported by a GI Bill stipend.

Kelly provides spectacular art history lessons. He addresses Byzantine art, Romanesque architecture, Donatello's bas-reliefs, and his beloved Isenheim Alterpiece by Grunewald. Kelly says, "In Boston, I developed my eye from the drawing. In Paris, I was fascinated by what my eye saw in the way that Paris is built, its 'mesure.'" During his student days, Max Beckmann came to lecture. In Paris, he got to know Brancusi, Calder, Arp, Picabia, and Giacometti.

Ellsworth Kelly drives me from the studio to his home down the street, a white house with white shutters built in 1815. And while he now requires supplementary oxygen, he seems quite hale, his voice strong.

The artist remarks, "I feel my latest piece is always my best. With the painting, it's that way when I finish it. After I finish a series of six or seven works that I am working on, there's usually one that I like best. When I'm painting the two panels of a relief and they are put together, I believe it has achieved what I wanted."

We are seated in his dining room, beneath some small inked faces by Matisse, a late Braque, and an Elizabethan era portrait of a Danish king. Kelly remembers visiting Miro on the island of Majorca in the 1960's. "Miro asked what's going on in New York, and we spoke of deKooning and Pollock. He said, 'I'm being forgotten.' I said to him: ' No, you are Miro!'."

Ellsworth Kelly begins to discuss a cathedral project, and suddenly bursts into a wide smile and says, "My glasses are reflecting the lights of the ceiling in silvery shapes. They are long lines at the edge of the glass where the glass fits the frame and I see tall forms, like candles. They are very bright. There's one that looks very much like a sculpture I am working on. That is how some of my shapes arrive, by chance." He laughs, "These are the kinds of things I see. No one could ever photograph this. I keep looking and I wait for them, what I call revelations."

Kelly's work is on view at all three Matthew Marks galleries in Chelsea through June 29 and at Mnuchin Gallery until June 1. MOMA is exhibiting Kelly's 1970 Chatham Series through September 8.

Disclaimer: I originally interviewed Ellsworth Kelly for The Art Economist Magazine in honor of the unveiling of his Beijing Panels at the US Embassy.