Well, well... once again we're arguing about the role of government.

As he did in his second inaugural address, President Obama's State of the Union address reminded listeners that he twice ran and won on a role for government that goes well beyond that articulated by Gov. Romney in the campaign or Sen. Rubio in his SOTU rebuttal.

One of the most important fault lines in these debates is government action to correct a failure or serious inefficiency in the market. If you fail to see such failures, or misdiagnose them -- Rubio absurdly blamed the housing bubble and bust on government lending -- you risk exacerbating the problem and causing a lot of people a lot of economic pain.

Let me be much more concrete here by talking about the case of the Federal Housing Administration, or FHA. When the housing bubble burst in late 2007, the private system of housing finance collapsed. Once gravity reasserted itself and home prices fell by more than half in some of the hardest hit states, banks were stuck holding loans worth cents on the dollar, if that. They did what they always do in such situations: they deeply retrenched, flipping from vastly under-pricing risk to becoming hugely averse to taking on any credit risk at all.

The private housing finance market essentially shut down, meaning no liquidity (the once robust -- and reckless -- market for mortgage-backed securities disappeared overnight), no home loans, no refis, and no way forward. Until, that is, a few government agencies, including the FHA, stepped into the breach.

The FHA's been around since 1934, not lending directly to homeowners but insuring private mortgages on behalf of less advantaged borrowers -- over 30 million since its inception. It's always paid for its operations with fees from borrowers and never in its history has it needed any assistance from general government revenues. That's because even though it insures the mortgages of lower income buyers, it's always had high lending standards. And contrary to the Republican myth, it held to those standards during the boom, even though that move cost it market share, as private lenders went deep into subprime lending, pushing no-docs and low-docs and other toxicities.

But when the crash hit, the FHA took on more risk than they ever have before, vastly increased their market share, and that led to some real losses. As recently reported by the Wall Street Journal, the FHA may soon "exhaust its reserves and need $16 billion from the U.S. government to cover projected losses."

And this has brought out predictable attacks, like by Rep. Jeb Hensarling ripping into the FHA and claiming that the agency is "morphing into Countrywide" and accusing it of straying "far from its original mission."

Not so. In fact, and to the contrary, it was by holding to its mission in the worst housing crash since its inception that the FHA incurred these losses. As Dave Stevens, former FHA director and now CEO of the Mortgage Bankers Association, pointed out, the losses the agency is now facing "are attributable to the critical function it played when the market turned and many private lenders refused to lend. Without FHA to step in, the housing crisis would have been measurably worse."

In fact, Moody's Analytics estimates that absent the FHA's actions, home prices would have fallen another 25 percent nationally.

And now that the housing market is starting to come back to life -- that's "starting," as in it's got a long way back to healthy conditions -- the FHA is doing exactly what it should be doing: getting back to pre-crisis levels of lending standards and market share.

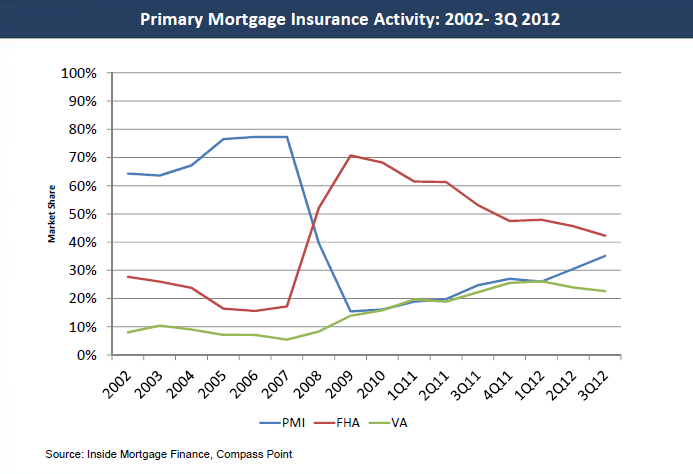

The figure below tells the story quite effectively. It's the shares of purchased mortgages utilizing mortgage insurance backed by "primary [or private] mortgage insurance" vs. FHA insurance (the VA also provides mortgage insurance for vets). You clearly see the private insurance function crashing and the FHA stepping up. Moreover, you see the FHA already unwinding, as it should be, as the PMI comes back up.

Source: FHA

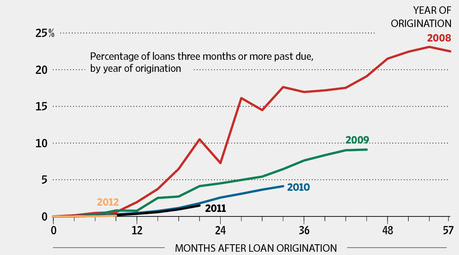

In addition, as the next figure shows, courtesy of the WSJ, each year that we move further from the crisis, the quality of FHA issuances improves.

Source: WSJ

Former White House housing finance expert Jim Parrott is one of the clearest thinkers I know on these issues, and here's the way he put it:

As with the GSEs, the FHA's current market size is not too big because they are lending to people they shouldn't be lending to, but because the private market is not yet comfortable taking on the credit risk of borrowers who traditionally would have gone to them instead of the FHA. The size of FHA is not a sign of an unhealthy FHA, but of a market that just hasn't fully recovered.

That's the key: to recognize the market dynamics. To accurately diagnose, as best you can -- this is economics, not physics -- when the market's failing and when it's recovering. When Keynesian stimulus is needed and when its not. When the safety net needs to ratchet up and when it should fall back. When staid government housing agencies that have quietly and effectively provided secondary insurance for decades need to get their risk on and when they should get their risk off.

To be fair, it's of course the case that it's not just markets that fail but government too. One reason the FHA is currently over-extended is because Congress nudged them towards a policy called seller-financed down payment assistance, a scheme by which sellers cover the down payment on the home loan, meaning borrowers could get an FHA-backed loan with zero skin in the game, a recipe for highly risky lending. To their credit, FHA never liked the idea, but Congress resisted ending the program until late 2008. Were it not for seller-financed down payments, the FHA's books would be in much better shape (in fact, the losses from that program alone are close to the shortfall noted above).

So you have to pay attention to all these dynamics, to market failure and political overreach. Of course, if your ideology precludes their recognition, you won't know what to do when you hit the downturn and a lot of people will suffer for your ignorance. One interpretation of the president's two victories is that the majority of the electorate would like to avoid that unnecessary suffering. I'm with them.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.