Every war brings with it a unique culture, and demands a unique voice to tell its story. Photojournalist Tim Hetherington and writer Sebastian Junger may have found the voice, or voices, of the Afghanistan war.

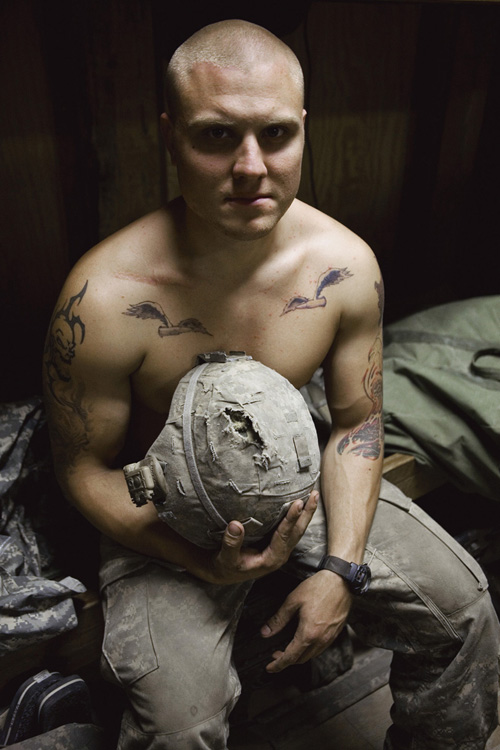

Hetherington's new book, Infidel, is a slim, small-format volume that has the look and feel of a family photo album -- the family in this case being B Company, 2nd Battalion, 403rd Infantry Regiment of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, which Hetherington photographed over the course of a year's deployment in the Korengal Valley of Afghanistan. Hetherington's imagery of Battle Company at ease in its hillside redoubt in the deadly Korengal comes at first as a bit of a surprise. While he includes shots of fighting, his book for the most part focuses on the moments when nothing happens -- the moments that make up the majority of a soldier's existence. The men drive golf balls from their mountain perch. They wrestle with each other. They smoke. Hetherington photographed their tattoos, their mottoes -- "God Hates Us All Forever" says one hand-made plaque -- and the centerfold pinups in their living quarters. You don't view these pictures as much as settle into them. Quietly, you feel yourself becoming part of Battle Company, as Hetherington did.

Junger too has a new book, War, which also tells the story of Battle Company. He mixes the personal and the expository, in the tradition of Michael Herr's Vietnam saga Dispatches. Like Infidel, Junger's book never strays far from the reality of the soldiers they lived with. The intent seems to be as much political and artistic. As Hetherington put it in this interview on PBS, "Symbols or representations of soldiers are often claimed by the far left and far right to mean a certain thing, and we do these men an injustice by not digesting fully their reality."

Last week I met with with Hetherington over coffee in New York. He's been busy, promoting his book and the documentary film, called Restrepo, that he and Junger made about Battle Company. Hetherington only recently learned that Restrepo, which was released in theaters last summer, had been shortlisted for an Oscar nomination. (A slightly longer version will air on the National Geographic Channel on November 29.)

And just two days before we met, he had been in Washington, D.C. to see one of Battle Company's men, Staff Sergeant Salvatore Giunta, become the first living soldier to receive the Medal of Honor since Vietnam. When it became clear the Giunta would receive the medal, Hetherington flew to Italy, where Battle Company was stationed when it was rotated out of Afghanistan, and filmed the soldier talking about the night that he ran into fierce enemy fire to save three friends, one of who later died. By the time President Obama presented the medal on November 16, the clip of Hetherington's interview with Giunta was already up on the Internet, where it could be sought out by, among others, the 37,000 people who have "liked" Restrepo on Facebook.

"You begin to have a community of people, and you begin to have dialogue with them," Hetherington told me in New York. Maybe only a photojournalist who has slogged through the most dangerous places on earth, only to wonder if anyone will ever see his pictures, could truly appreciate that kind of thing.

Hetherington, who was born in Liverpool, studied literature at Oxford but later turned to photography because he thought it offered "new ways to tell stories" for a 20th-century audience. In the late '90s he learned filmmaking, and through the first decade of the 21st century he's been experimenting with narrative and media. His book Long Story Bit by Bit: Liberia Retold combined pictures, interviews, history, and memoir to tell the story of his work in that country from 2003 to 2007.

With Infidel and Restrepo, the range of his story-telling has widened, from a magazine story (the project began as an assignment from Vanity Fair) to books, film, and the Internet. Though each of these projects stands alone, they, and Junger's book, should rightly be seen as a single, remarkable work--perhaps the first great piece of literature to come out of the war in Afghanistan.

The work is haunting, but in its own particular way. Hetherington's imagery of Battle Company isn't the hot history of Robert Capa's D-Day images, or the epic tragedy of Larry Burrows's photographs from Vietnam. Its reality is more intimate.

The haunting comes later. The book concludes with the voices of the soldiers themselves, who in a series of interviews manage to describe the fractured nature of reality in war.

"The funny thing about bullets is you'll see them do some crazy things," says one member of Battle Company. "A bullet came in through my back and exited through my stomach, and other than hitting through my lung and a small part of my intestine, it hit no other major organs...bullets are strange. They have their own path and they do their own thing."

For Hetherington, who worked with a still camera and a video camera at the same time, the trick was to understand which story-telling medium to use, and when. "I can't explain how I would choose. It was something I did instinctively," he told me.

The most acclaimed section of Infidel -- Hetherington's portraits of the men of Battle Company asleep in their bunks -- is an example of the power of his creative decision-making. We linger over these still images, looking at the men curled up, dreaming whatever dreams are to be dreamed. Here they are not warriors, but boys, exposed and entirely vulnerable.