Senator Bernie Sanders' amendment for a partial audit of the Federal Reserve's operations by the Government Accountability Office still needs an important requirement. The GAO must perform a diligent independent audit of the more than $2 trillion issued by the Federal Reserve in the United States and sent to foreign countries. The GAO should pay particular attention to Senator Bernie Sanders' floor statements in presenting the amendment so that the intent of the Congress is carried out. If the GAO relies blindly on the veracity of Fed records without thoroughly auditing the source details, the audit will fail.

I have had experience with accounting cover-ups by the Federal Reserve when I assisted House of Representatives Financial Services Committee Chairmen in their investigations for 11 years. These problems included severe accounting problems in the cash section of the Los Angeles Branch of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank which held $80 billion in currency and coin in their vaults according to Financial Services Committee Chairman Henry B. Gonzalez. I also assisted Chairman Gonzalez in uncovering corrupted accounting problems at the Boston Federal Reserve Bank that was handling the Federal Reserve's 50 plus contracted airplane fleet. Chairman Gonzalez wanted the Janet Reno Justice Department to pursue the corruption that was found. Justice diverted it to the Federal Reserve's Inspector General. He is internally appointed by the Fed officials who also authorize his budget . The Fed closed down the airplane operations at the Boston Fed Bank and moved it to the Atlanta Fed Bank. They tried to take action against their own courageous Fed employees who testified in Congress in 1997 and helped expose the corrupted bookkeeping.

These are some of the details that are described in my book Deception and Abuse at the Fed. Chapter 5, "Valuable Secrets and the Return of Greenspan's Prophetic Touch," presents additional severe problems at the Federal Reserve which should draw the close scrutiny of competent auditors. These problems have direct bearing on faulty Fed operations and should not be hindered by waving the Fed's mantra of independence. The Fed operates on a budget which is internally approved and is not even carried on the federal government's budget . At the very least there should be accountability for what they have done. That will not harm good monetary policy that can be carried out in large part by members of the Fed's Board of Governors who can serve for 14 years and can only be fired by impeachment which has never happened. Accountability will help to prevent corrupt operations.

What follows is an excerpt from Deception and Abuse at the Fed: Henry B. Gonzalez Battles Alan Greenspan's Bank, 2008. Courtesy the University of Texas Press.

*****

Chapter 5 -- Valuable Secrets and the Return of Greenspan's "Prophetic Touch"

Billion-Dollar Secrets

Information about plans by the Federal Reserve to change interest rates could be turned into huge profits if it were known before the policy was made public. And it is wishful thinking to pretend that millions, easily billions, of dollars have not been made using just such inside information from the Fed. The Fed's secrets have been widely disseminated to its employees and the favored few. Suppose someone was able to obtain definite information that the Fed was going to lower short-term interest rates (which would translate into higher prices for short-maturity bonds--interest rates and bond prices are inversely related) and that such a change in policy was not publicly known or anticipated. He or she could buy a security in a market outside the United States, say, a security sold in Europe that entitles the holder to exchange it for a bond in the future--a bond futures contract.1 The asset could be sold for a higher price after the Fed moves and bond prices rise. These securities may be purchased for less than half a percent of their face value in cash. A trader who purchased a large number of these securities could earn a very large profit in one day from a drop in interest rates. Rather than directly take a position in the market, a leaker or the favored leakee could sell the information to others.

It is very difficult to stop these leaks. One necessary step is to severely limit the number of people at the Fed with access to interest-rate policy information. This has not happened. Hundreds of Fed employees--over 500 of them--are directly involved in the secret meetings or in preparing the information discussed at them. Making matters worse, people not employed by the Fed, who have never had the limited background check that a new Fed employee receives, have been admitted to these secret meetings. Such visitors have included members of foreign central banks from Russia and China as well as academics from the United States.

There are two important components of this information: the loan rate--the rate at which U.S. banks can borrow money from the Fed, also called the discount rate--and the interest rate that the Fed targets in the market for short-term loans between banks, also known as the federal funds rate.2 Both are often changed together, so knowledge of a change in one generally provides information about the other. The nine directors at each of the twelve Fed Banks (108 directors) vote on the discount rate set by the Board of Governors. There may be extended discussion at each Fed Bank by the directors, bank officers, and staff in order to convince themselves that they are doing something meaningful, not just rubberstamping orders from Washington. Then the rubber-stamp ritual occurs, sometimes with a slight delay from some of the Fed Banks.

Even when the information discussed by the 108 directors and the Fed staffs is related to holding the current level of interest rates, it is still inside information that can be exploited for profit, especially if market participants have been expecting a change in interest rates.

"We're Beginning to Look like Buffoons"

At the FOMC meeting on December 19, 1989, Greenspan warned about the ill effects of ongoing leaks from the FOMC's supposedly secret meetings: "I would like to raise again a problem that continues to confront this organization with continuous damaging and corrosive effects, and that is the issue of leaks out of this Committee. We have had two extraordinary leaks, and perhaps more, in recent days: one in which John Berry at the Washington Post in late November had the time and content of a telephone conference; previous to that we had the Wall Street Journal knowing about telephone conferences and knowing a number of things that could only have come out of this Committee."3

Greenspan then suggested specific reporters who received the information: "I don't know whether the leaks are directly to Alan Murray, [Wall Street Journal ] who has the clearest access, or to John Berry [Washington Post] or Paul Blustein [Los Angeles Times]."4 Greenspan warned about the harm to the Fed's reputation: "As best I can judge from feedback I'm getting from friends of ours, the credibility of this organization is beginning to recede and we're beginning to look like buffoons to some of them."5

This warning did not address the very severe problem of providing exploitable information to a select group. Similar activities at private sector corporations would be treated as crimes. Instead, during the short discussion at this meeting, Greenspan emphasized the need to keep what they said secret: "If [our discussions] start to be subject to selective leaks on content, I think we're all going to start to shut down. Frankly, I wouldn't blame anyone in the least. We wouldn't talk about very sensitive subjects. If we cannot be free and forward with our colleagues, then I think the effectiveness of this organization begins to deteriorate to a point where we will not have the ability to do what is required of us to do."6

Admonishing his colleagues about secrecy did not stop the leaks of inside information. Four years later he would promise to end the leaks, and there were many, and, as seen below, Greenspan was a suspect. He would try to make a case that leaks were "inadvertently provided (reporters) [to give them] enough of a sense of the policy," and hinted that even his briefings to administration officials may have produced leaks.7 This kind of inadvertent leaking could not explain the examples given in the testimony of Anna Schwartz. She testified that the contents of the Fed's directive (containing policy instructions) from "11 FOMC meetings out of 34" that "took place between March 1989 and May 1993" were reported in the Wall Street Journal within a week of each FOMC meeting.8 That sounded like blatant leaking of inside information--a direct line to one or more persons in the Fed. David Skidmore (who became a Fed employee) reported Greenspan's reply for the Associated Press:

Greenspan said, "A deliberate premature leak of information is repugnant." However, it is possible committee members, who include the Fed's regional presidents as well as the Washington-based board "may in fact have inadvertently provided (reporters) enough of a sense of the policy considerations to allow conclusions to be drawn." He said the Fed has tightened up its precautions against leaks and vowed that the next leak will be followed "by a full investigation that will include gathering sworn statements from all attendees." . . . However, [Greenspan] acknowledged that he has briefed "members of various administrations" because they needed to know about FOMC decisions in formulating other government policies. But that hasn't happened in the last year or so, he said, because the Fed hasn't changed its monetary policy.9

Selling Information for $100 a Minute: "1-900-ANGELL?"

Wayne Angell, an economics professor at Ottawa University in Ottawa, Kansas, and a Republican legislator in the Kansas House of Representatives, was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the Fed Board on February 7, 1986. He filled an unexpired term that ended January 31, 1994. He submitted his resignation on February 9, 1994, so that he would not remain in office until the installation of his successor.

His friendship with Chairman Greenspan and his reputation for being outspoken added to the interest in Angell's actions when he left the Federal Reserve. It was astonishing to find that Angell began selling interest-rate information a month after he officially left his position at the Fed. David Wessel and Anita Raghavan reported in a lead article in the Wall Street Journal on March 24, 1994, that Angell was in "hot demand" on Wall Street and was "actually charging some analysts $100 a minute for advice." They stressed that this kind of information could be very profitable: "After all, a Wall Street investment house can make--or lose--millions of dollars when the Fed moves short-term interest rates by a mere ¼ percentage point, as it did yesterday."10

The report also said that Angell "recently talked to a Wall Street stock analyst for 13 minutes to get his views on interest rates" and that the analyst received a bill one day later for $1,300. Another analyst, Elaine Garzarelli, an 'influential stock strategist' at Lehman Brothers, said she would "happily pay Angell $100 a minute." The Wall Street Journal article continued: "Ms. Garzarelli decided to talk to him one on one. She won't say what she paid, but she says it was worth it. 'He told me the Fed would probably tighten again,' she says. 'And he predicted the bond market would react favorably. And that's exactly what happened,' Ms. Garzarelli said."

Chairman Gonzalez thought this was unethical behavior and ordered an investigation. Gonzalez issued a press release asking if Fed interest rate information could be obtained by calling 1-900-ANGELL: "'Will I learn what happened at the last Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting if I dial 1-900-ANGELL?' Rep. Gonzalez asked. . . . 'I suggest that the Fed implement a nondisclosure agreement with employees who terminate employment with the Federal Reserve,' Rep. Gonzalez said in a letter to Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan."11

Gonzalez wanted to prevent inside information or what appeared to be inside information from being leaked or sold by present and former Fed officials. An inquiry indicated that laws forbidding the exploitation of inside information for profit on securities trading apply to public corporations, but apparently do not cover the Board of Governors, an executive branch agency.

The Fed Shares Secrets with Foreign Central Bankers

At a hearing on October 19, 1993, Greenspan attempted to reassure Congress on this issue: "I trust the problem of leaks is behind us."12 But that was not the case. In 1996 the Fed reportedly called on the FBI to investigate "an embarrassing leak of inside information that churned financial markets last week and badly soiled the Fed's reputation as a paragon of bureaucratic virtue. A Fed spokesman declined to comment Monday on the reported probe."13 Unfortunately, Bill Montague, who wrote this description in his excellent article on the Fed, was wrong about soiling the Fed's image. The severe problem of leaking exploitable information had apparently not injured the Fed's reputation. It was occurring for very basic reasons that the Fed has yet to fix. By declining to comment, the Fed once again achieved its efficient under-the-lumpy-rug sweep. There was little media follow-up. For many, the subject died and the chairman remained deified.

One year later, the House Banking Committee received information about non-Fed employees attending Fed meetings at which inside information was discussed. Congressmen Gonzalez and Maurice Hinchey (D-NY ) asked Greenspan about the apparent leak of discount information and the presence of these people at Fed meetings. Greenspan was forced to admit that some non-Fed people had attended Fed meetings at which the Fed's future interest-rate policy was discussed.14 Greenspan included a twenty-three-page enclosure listing hundreds of people at the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., and in the twelve Fed Banks around the country who had access to at least some secret Fed information about interest-rate policy.

The list included "visiting scholars" who had attended pre-FOMC meetings at three Fed Banks. Greenspan wrote: "At the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, over the 3-year period, a total of 28 foreign central bankers have attended 16 different Board of Directors meetings, including the discussion and vote on discount rates." Those attending included "central bankers from Bulgaria, China, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Russia."15 Gonzalez presented a table showing the details of some of the foreign officials who had attended meetings at the Kansas City Fed Bank.

Following these disclosures and a letter from Gonzalez, Greenspan said the practice of allowing visitors to attend these meetings would end. There appears to have been insufficient oversight to verify whether this policy has been precisely and continually implemented.

This incident revealed a striking example of the Greenspan Fed's priorities: some of the information presented at the Fed Bank meetings attended by foreign central bankers was redacted by the Greenspan Fed before it was sent to Congress.

Greenspan Becomes a Prime Suspect

It is a rule of conduct at the Board of Governors that "Committee members are not to comment on monetary policy or the economic outlook" during the "blackout" period, which includes the week before an FOMC meeting "to the Friday of the week of the meeting. This means not giving speeches and not talking with reporters." So wrote Laurence Meyer, a Fed governor from June 1996 to January 2002.16

Meyer was surprised to see John Berry, a reporter then with the Washington Post, "coming out of the Chairman's office during the blackout period. I believe," Meyer continues, "that Berry and I would have been shot on the spot (perhaps by the Chairman himself) if we had been discovered together in my office during the blackout."17

Meyer rationalizes this kind of apparent leaking as a way of "signaling" Fed actions. The signaling can be "sanctioned" or "unsanctioned" by the FOMC members, according to Meyer: "The danger, however, is that the Chairman could prepare the markets for a move that the Committee might consider premature. That would put the Committee in the uncomfortable position of having to surprise the markets by not moving, or contradicting the signal and confusing the public. Of course, these consequences make it possible for the Chairman to occasionally use unsanctioned signaling to pressure the Committee into agreeing to a policy action when there otherwise might not be an overwhelming consensus for it."18

Meyer believes that unsanctioned signaling by the chairman is a "gray area." Meyer is wrong about the color. Leaking future Fed policy to the favored few, whether planned by one or more FOMC members or labeled with a euphemism like "signaling," is misconduct tinted darker than gray. Public servants who manage the central bank have an obligation to the citizens they serve to be forthright and credible stewards rather than leakers of exploitable inside information to the favored few. Meyer's observation places Greenspan on the list of suspected leakers. Meyer's description of signaling makes this incident seem like part of a broader and continuing practice at the Fed.

Unregulated Foreign Currency Traders with Advance Information on the Fed's Actions

In reply to a Gonzalez inquiry in 1994, the Fed noted that in the last five years it had transacted foreign-exchange business with fifty-eight foreign and domestic institutions (including private banks and brokerages) around the world. When the Fed called these parties and told them to buy billions of dollars of a currency, say U.S. dollars, the foreign entities received very valuable information that they could exploit for enormous profits. Gonzalez wrote to Greenspan: "A large trading company could earn many millions of dollars in profits in a short time period on this inside information."19 Earlier, Greenspan had tried to send a message that these actions were not worrisome: "Usually, these market participants very quickly inform the wire services." He added discordantly that even if they just dealt with "a single institution with information not generally known . . . the immediate counterparties have information on intervention at least a couple of minutes before the entire interbank market" (emphasis added).20

Would anyone have the audacity to make billions of dollars on inside information without calling the wire services? Would they be so ungrateful for their commission from the Fed that they would trade on their own account or leak the information to another trader before the Fed's trading became public? Apparently no one has come forward and telephoned the Fed about their exploitation of inside information. The remedy may well be for the Fed to simultaneously notify the media and the parties receiving orders; that way no exploitable inside information is passed to favored parties. Markets would quickly, and generally more efficiently, adapt to the Fed's actions.21

The legal limits barring the GAO from auditing foreign-exchange operations at the Fed should be lifted. The GAO should hire experts (not connected with the Fed) to examine these operations. Through investigations and oversight with trained experts, Congress should compel the Fed to adopt the best remedy for eliminating the dispersal of exploitable inside information.

"The Return of Greenspan's Prophetic Touch"

On Thursday, November 6, 2003, Greenspan gave a speech in Florida that drew enthusiastic praise for his ability to predict the future.22 A contribution published in the New York Times the following Sunday was entitled: "The Return of Greenspan's Prophetic Touch."23 It began: "Has Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, reacquired the oracle's touch?" The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported, on the day after the speech, that he had given "a carefully phrased endorsement" of optimistic predictions for the labor market: "The odds . . . increasingly favor a revival of job creation."24 The Los Angeles Times reported Greenspan as being "relatively optimistic" in the short-run.25 The Washington Post reported that Greenspan "in his most upbeat assessment of the U.S. economic outlook in years, said yesterday that the economy should soon start producing the kind of job growth that has been missing since the end of 2001."26

What was the basis for the claim of "the return of Greenspan's prophetic touch?" The day after Greenspan spoke, the U.S. Labor Department announced a turnaround in its estimates, from a decline in employment to a rise in employment. The Friday news release stated that nonfarm employment, which had fallen in the second quarter of 2003 and had been reported as falling in August and September, was now rising. August and September employment figures were revised upward to show an average increase of 85,000 jobs a month in the third quarter.27 Although there had been a decline in the number of claims for unemployment insurance on Thursday when Greenspan spoke, the big labor market news came the following day.28

The Fed chairman may sometimes have sounded as though he knew the future state of employment, and he might have, although there is no direct evidence of it. Professor Alan B. Krueger wrote about confidential governmental data that are passed to the president, the Federal Reserve Board chairman, and the Treasury secretary before they are made public. Greenspan, Krueger states, "has an agreement with the Bureau of Labor Statistics to receive monthly employment data for manufacturing, mining and public utilities two or three days early, ostensibly so the Fed can produce its industrial production statistics. . . . Surely, the chairman's reason for wanting data early is a ruse; he wants an advanced hint at where the economy is headed. Providing prerelease data makes the chairman seem omniscient and helps the Fed and Treasury outfox the markets."29 The sharing of "business data" between governmental agencies was increased by a law passed in 2002.30

Perhaps Greenspan's crystal ball had a note under it from the Department of Labor, which also may have appeared when he made his famous remark about "irrational exuberance." When Greenspan described stock market attitudes as evidence of "irrational exuberance," prices plunged on world financial markets. He included an addendum: "a drop in stock prices might not necessarily be bad for the economy." That was on Thursday night, December 5, 1996.31

It was bad news for investors who believed the Fed was signaling an interest-rate increase. The Associated Press reported: "Many investors were skittish ahead of the figures, fearful that news of a booming economy would lead Greenspan to tighten interest rates." His remarks on Thursday night sent stock prices falling and "contributed to the biggest drop in Japanese shares" that year. There is a question but no evidence about whether Greenspan had knowledge of the report to be issued the next day, one that would calm the financial markets.

The next morning, Friday, the Labor Department reported a smaller-than-expected rise in employment, and this news reduced concern that the Fed would raise interest rates to slow the economy. There was a recovery in prices for U.S. Treasury bonds.

By using inside information to embellish a record for accurate predictions, an official can lend undue credence to his or her other, less reliable predictions. The biased devotion of the Fed-watchers industry can increase the amount of false information and volatility in financial markets.

Senior members of the Banking Committees in the House and Senate who have security clearances should be kept informed by Fed witnesses of any confidential economic data that are coded in their testimony or responses and cannot be made public before the embargo date for their public release. No Fed official with knowledge of embargoed economic reports should manipulate the press and the public with speeches or testimony that use this inside information, unless some national emergency requires that action.

Manipulating the Media

Trying to persuade reporters, spinning a message, leaking a proposal to test its reception, and anonymously dumping on opponents are all common practices in politics. They are in many cases the symptoms of a vibrant democracy. Persuasion is a vital tool for successful politicians, whose reelection depends partly on their ability to persuade other legislators to support their proposals so they can establish a successful record. There are ethical and, perhaps, legal limits to such actions. These limits are especially relevant for the Fed's unelected officials.

Although Greenspan did not hold formal press conferences, he held off-the-record conferences with selected reporters. As Laurence Meyer explains, "The use of reporters as part of the Fed's signal corps is not official Board or FOMC doctrine." Although Meyer describes the practice, he notes that the public-affairs staff and Greenspan "like to pretend it doesn't happen": "He typically relies on a small group of reporters. John Berry, longtime reporter for the Washington Post and now at Bloomberg, is most widely recognized in this role. The Wall Street Journal reporter covering the Fed--it was David Wessel, then Jake Schlesinger, and most recently Greg Ip during my term--was also a regular member of the signal corps."32 Many reporters are likely to consider their inclusion in this kind of selective access important for their employment, although exclusion awaits if their reports include criticism of the Fed.33

There are some pieces of vivid evidence. Jim McTague has covered the financial scene from Washington, D.C., for many years. McTague is the Washington editor of Barron's, one the country's most prestigious business publications. He spoke about his relationships with the Fed on national television in 2002.34 He related that he had a one-on-one conference with Greenspan, whom he found cordial but uninformative. After he wrote a column that suggested that Fed policy had contributed to the defeat of President George H. W. Bush, he was told that he was banned from further conferences with Greenspan.

Also, McTague's report on the 1993 hearing at which Fed officials misled Congress was likely regarded as unfavorable, even intolerable, by the Fed. He compared Greenspan's congressional testimony about the transcripts of the Fed's meetings to an act by a double-talking comedian. McTague told Congressman James Leach (R-IA) about his being banned. According to McTague, Leach told him to write a letter to the Fed. A Fed spokesman replied to McTague's letter by telling him he had never been banned. After relating this story on national television in 2002, McTague was called by the Fed and told he was banned again. This stick-carrot-stick attempted manipulation might have intimidated a lesser reporter. In this case it failed.

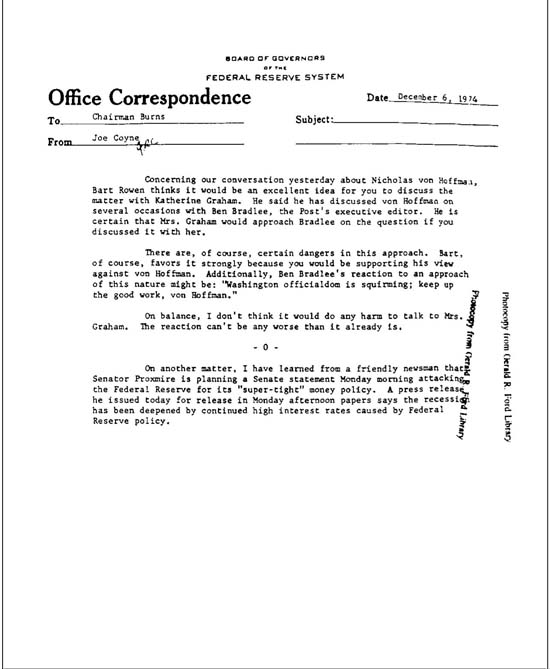

Nicholas von Hoffman was a well-known columnist for the Washington Post and a commentator for the "Point-Counterpoint" segment on 60 Minutes.35 His criticism of the Fed led to an internal Fed memo being sent to Chairman Burns (Figure 5-1), suggesting the Fed chairman contact the owner of the Washington Post.

Figure 5-1. Memo from Joe Coyne to Fed chairman Burns, December 6, 1974. Coyne urges Burns to talk to Katharine Graham, owner of the Washington Post. Reporter Nicholas von Hoffman had been harshly criticizing the Fed. Source: Arthur Burns Collection, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

In the memo, dated December 6, 1974, Joe Coyne, who handled public relations at the Fed, told Burns that he had discussed the von Hoffman matter with Bart Rowen, who was a business columnist for the Washington Post; that Rowen thought "it would be an excellent idea for you [Burns] to discuss the matter with Katherine [sic, Katharine] Graham," the owner of the Washington Post and the daughter of a former Fed chairman; and that Rowen had discussed the von Hoffman matter with the Washington Post's famous editor, Ben Bradlee. According to Rowen, Graham would approach Bradlee about the Fed chairman's discussion of the von Hoffman matter. Coyne warned the Fed chairman that there were certain dangers: "Ben Bradlee's reaction to an approach of this nature might be: 'Washington officialdom is squirming; keep up the good work.'" Despite this caution Coyne thought the chairman of the Federal Reserve should contact the owner of the leading newspaper in the nation's capital because the "reaction can't be any worse than it already is."

There has been little media coverage of Fed operations such as those discussed in this book. After an initial story, there is little meaningful follow-up, which allows the Fed to keep brushing problems under its lumpy rug. A follow-up would invite retaliation from the Fed. A reporter wishing to meet with the Fed chairman for a lovely off-the-record chat would have disappointing news for his or her editor if a story critical of Fed operations ended this access. Nevertheless, some reporters have written important critical stories about flawed Fed operations. A few examples related to problems discussed in this book:

• Alan Abelson, "Irrational Adulation," Barron's, July 22, 2002.

• Stephen A. Davies, "Fed May Be Stifling Criticism by Hiring Outside Academics," Bond Buyer, November 4, 1994 (on Fed payments to academics).

• Gene Epstein, "No Place Like Home; Looking for Inflation, Chairman Greenspan? Have We Found Some for You!" Barron's, August 2, 1999 (on the need for major restructuring of the Fed).

• Jim McTague, "Greenspan Has Himself to Blame for Fervid Interest in Transcripts," American Banker, December 1, 1993.

• Bill Montague, "Fed under Fire; Critics Say Public Is Being Shortchanged," USA Today, September 24, 1996 (on Fed leaks of inside information).

• Paul Starobin, "The Fed Tapes: The Revelation That the Federal Reserve's Chief Policymaking Body Has Kept Secret Records of Its Meetings Has Raised Questions about the Fed's Integrity and Accountability to Congress," National Journal, December 18, 1993.

• John Wilke, "Showing Its Age, Fed's Huge Empire, Set Up Years Ago, Is Costly and Inefficient," Wall Street Journal, September 16, 1996 (on waste and inefficiency in Fed operations).

They deserve praise for serving the public interest despite the type of retribution and attempted manipulation that the country's most powerful peacetime bureaucracy has employed.

Notes

1. "Bond" is used as a generic term for debt instrument. The security is a contract to buy three-month Eurodollar time-deposit futures at near today's prices at a specific date when the Fed moves. In September 1998, when Gonzalez left Congress, a $1 million contract, called the "trading unit," could be purchased for $470.

2. The Fed determines the interest rate at which it will lend money to financial institutions. It lends this money through a window located in the lobby of each Fed Bank. The loan facility is called the Discount Window because of the original practice of lending money against part of the value of the loan document, a discounted value, that the commercial banks submitted as collateral. Today the loans extended through the Discount Window are straight advances of money, with government securities used as collateral. Originally, each Fed Bank set its own loan rate or discount rate. That practice changed with the 1935 reorganization of the Fed.

3. FOMC meeting transcript, December 19, 1989, morning session, 54. Available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/FOMC/transcripts/1989/891219Meeting.pdf.

4. Ibid.; newspaper affiliations added.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.; bracketed are words on the transcript.

7. See the testimony of three witnesses, Robert Craven, Anna Schwartz, and James Meigs, in H.R. 28, the Federal Reserve Accountability Act of 1993: Hearing before the Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, October 19, 1993.

8. Wall Street Journal, October 19, 1993, based on Michael T. Belongia and Kevin Kliesen, "Effects on Interest Rates of Immediately Releasing FOMC Directives," Contemporary Economic Policy 12 (October 1994): 79-91.

9. David Skidmore, "Greenspan Defends Secrecy Surrounding Key Central Bank Committee," Associated Press, October 19, 1993. In 2006, Skidmore was assistant to and chief spokesman for the Board in the Office of Board Members, which conducts public relations and lobbies Congress.

10. David Wessel and Anita Raghavan, "A Glowing Glasnost at the Fed Is Dispelling a Lot of Its Mystique," Wall Street Journal, March 24, 1994.

11. Henry Gonzalez, press release, May 19, 1994.

12. H.R. 28, the Federal Reserve Accountability Act of 1933, 12.

13. Bill Montague, "Fed under Fire; Critics Say Public Is Being Shortchanged," USA Today, September 24, 1996.

14. Greenspan to Gonzalez, April 25, 1997.

15. Ibid., 2.

16. Meyer, A Term at the Fed, 99.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid., 100.

19. Gonzalez to Greenspan, August 11, 1994, 2.

20. Greenspan to Gonzalez, July 5, 1994, 5.

21. Gonzalez suggested this solution in a press release dated August 11, 1994.

22. Greenspan, speech at the Securities Industry Association annual meeting, Boca Raton, Florida, November 6, 2003.

23. David Leonhardt, New York Times, November 9, 2003.

24. Michael E. Kanell, "Jobless Claims Nosedive; Economy Ratchets Up," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, November 7, 2003.

25. Warren Vieth, "Fed Chairman Predicts Upturn Soon in Hiring; Greenspan Also Warns of Danger from Budget Deficits," Los Angeles Times, Business sec., November 7, 2003.

26. John M. Berry, "Greenspan Buoyant on Jobs Outlook," Washington Post, Financial sec., November 7, 2003.

27. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Employment Situation Summary," November 7, 2003, 1: "Nonfarm payroll employment rose by 126,000 in October [2003], following a similar increase (as revised) in September."

28. Greenspan first mentioned the labor market in his speech by saying: "There have been some signs in recent weeks that the labor market may be stabilizing." That is difficult to interpret, since it could be "stabilizing" at a low number. Later in the speech, Greenspan turned to a more optimistic description of the labor market: "The odds, however, do increasingly favor a revival in job creation."

29. Alan B. Krueger, "Economic Scene: In Numbers We Trust, Provided They're Safe from Political Meddling," New York Times, May 30, 2002. The Fed sometimes signals future monetary policy changes to an administration. John Berry reported how Greenspan passed information to the Clinton administration about raising the Fed's interest-rate target in 1994 ("Fed Kept White House Informed on Rate Increase," Washington Post, Financial sec., February 12, 1994).

30. The Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2002 (CIPSE A) "authorized the limited sharing of business data among the Bureau of the Census, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BE A), and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for statistical purposes. Allowing the agencies to share certain businesses data has improved the accuracy and reliability of economic statistics" (Randall S. Kroszner, "Innovative Statistics for a Dynamic Economy," remarks at the National Association for Business Economics Professional Development Seminar for Journalists, Washington, D.C., May 24, 2006; available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/Boarddocs/speeches/2006/20060524/default.htm). Fed governor Kroszner "helped lead the effort to urge passage of the CIPSE A." The act was in part intended to limit the duplication of estimates of the same variables by different governmental agencies. There is no direct evidence available that Greenspan used inside information or knew that the information from the Labor Department may have been sent to the Fed.

31. The Associated Press reported on Greenspan's statements: "How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values," Greenspan, renowned for intentionally leaving his comments open to interpretation, said in a speech at the American Enterprise Institute. Greenspan also said that a drop in stock prices might not necessarily be bad for the economy. The markets took Greenspan's comments as a sign that the Federal Reserve might be willing to raise interest rates to squeeze out any speculation in the market. "We as central bankers need not be concerned if a collapsing financial asset bubble does not threaten to impair the real economy, its production, jobs, and price stability. Indeed, the sharp stock market break of 1987 had few negative consequences for the economy," he said. "Greenspan Warns of 'Irrational Exuberance' in Stock Market," Associated Press, December 6, 1996.

32. Meyer, A Term at the Fed, 98.

33. As in the press rooms in the House and Senate, attendees at the Fed chairman's secret (from the public) off-the-record press conferences should be in the hands of the press where press credentials are verified.

34. Jake Lewis and I organized a symposium held at the National Press Club on January 7, 2002, entitled "The Federal Reserve: Reality vs. Myth." It was sponsored by Ralph Nader and televised by C-SPAN. I participated in a number of sessions.

35. Nicholas von Hoffman left the Washington Post and became a columnist at the New York Observer. His books include Capitalist Fools: Tales of American Business, from Carnegie to Forbes to the Milken Gang (1992) and Citizen Cohn (1988), a biography of Roy Cohn. He also wrote the libretto for the opera Nicholas and Alexandra by Deborah Drattell. See his biographical note at http://www.lamama.org/archives/2001_2002/Geneva.htm.