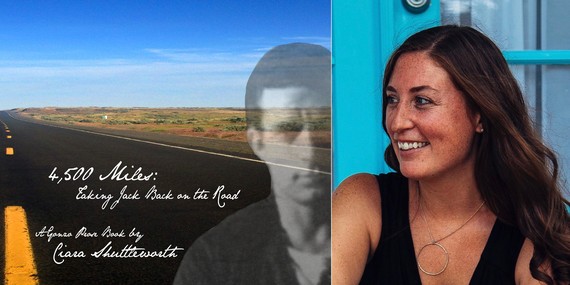

Book cover of 4,500 Miles: Taking Jack Back On the Road and the author photo of Ciara Shuttleworth. Photo courtesy of Humanitas Media Publishing and Drew Perlmutter. Book cover photo edited by Pamela Theodotou.

Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life. -- Jack Kerouac, On the Road

If the Beat Generation was about questioning life and the standard values of society, spiritual exploration, and delving deeply into personal experiences that could have a transformative effect, Jack Kerouac, as one of the core members of this group that came out of post-WWII American reality, was one of its exemplars. His classic, On the Road, has continued to affect generations long after its release on September 5, 1957.

Named as one of the 100 most important English-language novels of the 20th Century by the Modern Library and of 1923-2005 by Time Magazine, the New York Times considered it "the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by the generation Kerouac himself named."

Having spent a residency at the Jack Kerouac House in Orlando, Florida in 2015, writer and artist Ciara Shuttleworth came to appreciate Kerouac enough that when she was on her way home from Orlando to the scablands of Washington state, she decided to take a Jack Kerouac cut out, "Flat Jack" with her as she took her own road trip West.

Early on, the experience took on a life of its own, influenced by the writer whom she had just come to know much more personally. And as Kerouac had, she wrote about the places, people, and events she experienced along the way. Jack Kerouac's was enough of an inherent presence, she started to consider him a kind of traveling companion.

The result was 4,500 Miles: Taking Jack Back On the Road, a collection of "gonzo prose" and photographs, later edited for the book by award-winning filmmaker, photographer, and writer Pamela Theodotou, released today by Humanitas Media Publishing, nearly 60 years to the day On the Road was published.

The book has received praise from Bob Kealing, author of Kerouac in Florida: Where the Road Ends, Summer Rodman, President of the Jack Kerouac Project in Florida, and Dr. Brad Hawley of Oxford College of Emory University, who provided the preface to Shuttleworth's book. Each knows Kerouac's history and work well, and they were surprised someone of Shuttleworth's generation could capture Kerouac's voice so perfectly, especially considering Shuttleworth had not known as much about Kerouac before her residency.

But Shuttleworth's discernment and talent, and whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Ploughshares, The Norton Introduction to Literature, and The Southern Review, naturally shone through following immersing herself in the life and work of the man for whom the residency was named.

Below is an interview with Shuttleworth regarding Kerouac, the Beat poets, her experience on the road, and the resulting book that took a year to edit and produce, being both a written and photographic documentation of those 4,500 miles.

What was your first exposure to Jack Kerouac and Beat literature?

College. I read On the Road and wasn't impressed. Or rather, it made an impression: I was turned off by the taking off and leaving the women behind. My father is a chauvinist but somehow raised three daughters who believe they have the same rights and abilities as men. Even in college, when I was getting over a lot of conservative viewpoints, I guess I took offense to On the Road because I didn't like the idea of being left behind, of not being part of the action. Who knows, really. That was a long time ago. I was reading a lot of Hunter Thompson and Vonnegut and Vollmann and such. I found a lot more to like there. I must have read Ginsberg during that time, too, but I didn't read Ginsberg with any seriousness until I was in my mid-twenties in San Francisco. And then I went to art school and a mentor, Bruce McGaw, told stories about how he'd worked at City Lights and a painting of his hung behind Ginsberg the first time he read "Howl." And then I reread the poem and was struck. When Kelly Davio was the editor of Los Angeles Review, she published a poem of mine, "Seven Years in San Francisco," which was my ode to the 20-somethings of the dot-com-era San Francisco that I lived and loved in. The poem was highly influenced by "Howl." Ginsberg had beautifully captured his people and time with breathlessly long lines and I wanted to do the same; there was so much said in so little space. I began to understand, finally, in grad school (when I wrote the poem), that the Beats were simply trying to live their lives, counter-culture as they might have been. It wasn't until my residency at the Kerouac House, however, that I really read Jack's work, that I started to research and understand Jack (and through him, I suppose the Beats as well).

In the book, you are having conversations with Jack's ghost...how do you imagine he was the same or different than he is popularly perceived?

My time at the Kerouac House gave me a completely different view of Jack. My perception of him prior to the residency was that he was a masochistic asshole, and I think that's a common misconception. Jack's views--and actions and reactions to the world--were dichotomized by his Catholic upbringing and his love for what he was learning about Buddhism, by the stoic, stodgy nature of his mother and the wild relentlessness of the lives of writer and artist friends. He so wanted to be Neal Cassady, but he didn't have the charm or swagger, nor did he have the needle-loose moral/ethical compass. He wanted to be a good man but couldn't figure out exactly what that meant. There is so much more I need to learn about and from Jack.

You had a residency at the Jack Kerouac House in Orlando. What was the residency like, and what is the reaction of the community to the residents and residency?

The residency was the best; it will be hard to top. The community is beautiful, embracing. The writing community in Orlando loves the Kerouac House and the residents, gives the residents ample invites to events (to go to but also to participate in). The residency and the warmth from the community were gifts, and my only way of repaying the kindness in any way was to write as much and as well as I could.

What is your favorite line or passage from Kerouac's work?

Without a doubt: "What is that feeling when you're driving away from people and they recede on the plain till you see their specks dispersing? - it's the too-huge world vaulting us, and it's good-bye. But we lean forward to the next crazy venture beneath the skies."

This quote means so much to me. I love people and I love spending time with people I love. I also love the leaving. The hoping I'll see them again. The knowing I have more adventures ahead...

But there is also the end of Big Sur. Many see the ending as sad, but really it's exactly what this quote encapsulates. It's a letting go and moving forward. Big Sur doesn't have an unhappy ending. It's an emotionally tumultuous book, but in the end he finds resolution. He knows he is moving on and that everyone in his wake will be fine.

What do you think is the influence today from Kerouac and the other Beat writers?

When at the K House, there were weird kids who'd come by. One in particular comes to mind. He came up the steps like he owned the place. I was just going out to write, as I so often did, on the porch, and I startled him. So he kind of scurried off and pulled a pizza box from his trunk, and a sharpie, and a solo cup of whatever he was drinking, and posted up on the lawn to scribble on the box. He was insolent and rude, really confrontational without cause, so I told him that the front of the House wasn't even where Jack had lived, that he needed to take his things and leave. It disturbed me because that wasn't Jack at all. Jack was love and curiosity. All the other "pilgrims" who came by the House were definitely Jack's people; this guy wasn't.

One day, filmmakers stopped by and one, Ashley, had her baby along. I was instantly taken with them and gave them a tour, directed them to the back stoop for accurate recreation photos. They stayed for some time and I held the baby, Miles (I'm usually not taken with babies, but he was and is something special). I wrote a poem about him that night. I am in touch with his mother. I believe that most of the people who came to the House came because Jack wanted me to meet them for one reason or another.

Jack's influence is still prevalent. For better AND for worse. There are those who understand how complex he was, how his writing was everything to him. And there are those who use their love for what they believe he was as an excuse for bad behavior.

The stream-of-consciousness style has led to a lot of poor writing, but those who understand the amount of work he put in before writing like that...have benefited. I write 90% of my work in my head before it hits the page, so I understand Jack's process a bit.

Ginsberg would have loved social media. Ferlinghetti probably faired best out of all, was a powerhouse for publishing works that otherwise may have stayed in drawers, but City Lights is more of a quiet library now than a hopping literary meet-up place.

I doubt the Beats will ever vanish; they will always be important. There are those who love Hemingway and those who love Kerouac. I lean more toward Kerouac now. He was one of the greatest American writers of all time. If he were still alive, he'd be floored by that, and I tried to capture that in the book.

How would you describe the book, and what were the nuances you thought were important to include?

Nuances... His kindness. His curiosity for the world. Definitely the internal chaos, the battle between dichotomous selves. In a college art class, I read about masks made in an ancient culture to show the two sides of the face with relevance put on the difference between the two: one side showed the side others recognize us by, and the other showed our true self and our death wish. I wish I'd kept the essay so I could quote from it and give it credit.

As is true with many of my writer/artist friends, I live a large portion of my life in my head. A friend recently told me that I've hand-crafted a beautiful world for myself and it's nice when I let other people enter it. While I tend to be very careful who I let into that world, and when, and even how much or often, Jack was guilty of the same thing...only he wanted/needed to have as many people move fluidly through as possible. Depression hit him hard any time he wasn't either writing (as quickly as possible) all he'd experienced or out experiencing. But he was a wallflower in many ways, a watcher. He thrived off the chaos created by others and was drawn to those who created extraordinary experiences for him (whether he lived vicariously through them as a viewer or actually participated). In that way, he was a historical writer--he wrote of his time, and he wrote it as fiction so it wasn't necessary to be accurate...and so he could make himself a little larger in the stories. What my book does is turn things around on him. I made him the instigator. I was his sidekick, his co-conspirator. He was in the spotlight and yet he still shied away, still tried to watch me as if he'd go back to the typewriter and fictionalize our adventure.

The book was an opportunity to take an extended amount of time with a writer I'd newly come to respect, to ask him questions, to drink with him, to drive for miles within the confines of a car. There was no escape for either of us. This wasn't taking a writer I admire out for drinks or dinner; this was living with him for two weeks.

How was the trip back to Washington state from your residency? Any nuances or thoughts that don't appear in the book that you'd like to share?

Jack was ever-present. I would not have taken as many photos had he not been along. I wouldn't have taken the time to stop so often, to explore, to see the landscapes I traveled through as clearly. I knew I was writing this book but had no idea what the content would be, what I would write. While on the road, it would occur to me what Jack would do, so I'd do it. I took notes in a small Moleskine.

But even my interactions with people were different than they may have otherwise been. I had to look back at my experiences with people I visited and decide what could and could not be written about. A colleague from grad school--the visit was the only downer of the entire road trip. I should have left as soon as I walked into the depressed vibe of his house. Having Jack to bounce that off of--downplaying it in the book despite Jack believing I shouldn't have. But knowing that Jack understood that, that he'd downplayed his role in events (or the events themselves) so as to not upset his mother. I wasn't worried about upsetting anyone; I simply didn't see the point of making a deal out of it or making this guy feel bad for something that ultimately had no impact on my life. The book was about Jack rather than my reconnections or connections with people, so I tried to stay true to that while writing the book.

You come from a creative family, and you are not just a writer and poet, but an artist. How is being involved with multiple media a benefit to the different kinds of work you do?

As far back as artists go, they have been scientists, mathematicians, and writers in addition to making art. It's only been recently that we separate so strictly. We are a young species. Perhaps things will swing back in the other direction.

While my father raised us with an iron fist, one thing he never tried to tamp down was our creativity (that and athleticism). Poetry and art have always been a part of my life. I chose painting and drawing first because I didn't want to be a poet. Anything but. I didn't want to infringe on my father's territory, but I also didn't want to live the constant rejection that poets live. Friends tell me how great my publication history is, but if they looked at it as a rejection vs. acceptance batting average, they might be appalled. Hahaha! You have to be thick-skinned to attempt to put your work into the world. At the end of a year, however, I don't look at how many rejections I've had. I only look at the wins. And I've been lucky to have wins every year.

I always wrote while in the painting studio. I do math equations in my head while running. I geek out on science articles. Writing is something I've always done. It's akin to breathing in my family. So the writing comes first. But if I had all the time in the world, I'd also paint and draw every day. I'd research science curiosities. I'd help my sister make more films. Hell, maybe I'd even relearn guitar.

The summer after college, I was too heartbroken to paint. But I wrote. I wrote every day. And I've written almost every day since. When painting, I don't think; I only feel. What I've discovered is that on my best days of writing, the same is true (most days I don't write anything worth using, but who cares?). I love the smell of oil paint, the feel of a carbon pencil on cotton paper, the white canvas or page filling with a moment or emotion captured. How is writing any different? These colors and words have existed for a long time. Poetry is the one written art form that can capture what a painting can. It is bare-bones, stark, beautiful or macabre, nuanced. It can capture so much with so little. It's a secret language that you only have to feel to understand.

What have been your other inspirations as a writer, and as an artist?

I usually say the Pacific Ocean is probably my biggest inspiration: the immensity, the life within, the lore, the miles it stretches between people and places... But that's a cop-out answer and in truth, my biggest inspiration is my family. My younger sister, the filmmaker Jessi Shuttleworth, and I continue something started in childhood: we make up stories about people. We can sit anywhere and create entire lives for the people moving by us. We watch faces and body language. We create conversations between couples.

I am captivated by people. What we do out of fear or love. How poorly we communicate. What we are willing to fight for, to love in spite of better judgment.

Franz Wright's The Beforelife is the book that made me believe I should take my writing seriously. His work, more than any other writer's, has influenced how I look at and think about poetry.

Your work has appeared in many publications and literary journals in the last years. What do you find is the current state of the literary community and such journals and publications in the public sphere--are they, and the content that appears in them, as popular as they have been in the past? Have the audiences/readers changed? What kind of reaction have you received from them?

Online publications have become important. While I still prefer the printed journals, I believe my non-writer/academic friends are more likely to follow a link to read a poem I have online rather than buy a print journal (if they can even find it if they aren't in an urban location with good bookstores).

There are also journals like Tahoma Literary Review that are both print and online, which pleases me greatly because of the larger audience they cater to in that way.

The people who post every couple years that poetry is dead are fools. Poetry is thriving. It is transforming and transmogrifying (yes, it is changing in good and bad ways, as it always has). The work that matters and will last is the same as it has always been--the work that speaks to/of the human condition, to/of our time, to/of love and loss, to/of base emotions. Great art has always held a mirror up, regardless how many viewers refuse to see themselves, who turn away.

There is a lot of political poetry out right now because this is a political time, particularly regarding racism in America. Political poems are tricky because the poet should never TELL the reader how to feel, and yet the poet can persuade the reader in a direction through showing, through imagery. There is an audience for these poems that hasn't been there for other poetry. And that is a good thing because poetry (art of any kind) has always been at the forefront of change. Poets/artists have always been willing to take more risks.

Poetry matters most to non-regular-readers at weddings, funerals, presidential inaugurations, and other poignant times. What political poetry is doing is bringing in readers who would otherwise not be reading poetry. Which is good for poetry and good for the world.

The singer Beck has said in interviews that his albums are so diverse because when he goes to make an album, he thinks, "What am I not hearing right now that I want to hear?" I write about love and lost love and limerence because these are things I want to read more about and am not. I am currently most curious about how we deal with love and loss, with how many relationships look good on the outside but are broken (why do we project gold when inside is shit? why not simply leave? why are people so scared to be alone?).

Anything else you think it is important to include about the book, yourself, your past work in leading up to this?

I am grateful to Humanitas Media Publishing for contacting me two days into my road trip with Jack. Without the book offer, I would not have taken half the photos I took, would not have had the companionship Jack gave me (I so often asked myself what Jack would think of situations, people, the landscape, etc.).

There is a sense of wonder about Jack--I'm not the first to feel this way and won't be the last. It is important to note that Flat Jack's responses to my questions are based on the research I did, the conversations I had with people who have researched him. The exchanges between us are truly gonzo, but my intent was to be as true to Jack Kerouac as I possibly could.

4,500 Miles: Taking Jack Back On the Road was released today, September 5th, and will be available in hardcover, softcover, Kindle, and iBook. Further information may be found via http://www.humanitasmedia.com.