It was like a crappy divorce after years of passionate involvement. Seven seasons embroiled in the ups and downs, joys and heartaches, failures and triumphs of The Good Wife's Alicia Florrick, and we, the audience, were summarily dismissed with a literal slap, bereft of any expectation of a creatively authentic, emotionally satisfying conclusion to it all. With Season 7, Episode 22, the finale of a heretofore brilliant series, we watched as our heroine stumbled off post-slap, tugging at her designer suit, her always perfect hair ever-so-mussed; eyes teary, men gone, mentor betrayed, children confused, career on the precipice, and we, like Peggy Lee, could only ponder: "Is that all there is?"

I get it, good endings are hard to write. Whether a 1,500-word article dissecting Election 2016, a personal essay on the family road trip to Senegal or a full-length novel embroiled in Cold War espionage, the perfect ending can be an elusive beast, one that confounds many an excellent writer who finds no such struggle with any other part of the story.

Some analysts of this literary conundrum condescend with presumptions that audiences want only the tidiest of wrap-ups, rosy conclusions that propel protagonists to sail/ride/motorbike off into tangerine sunsets, while villains roast in a prison/grave/hell/bad relationship of their own Machiavellian doing. They snark that we require all t's crossed and i's dotted, every loose end bound, every subplot brought to obvious outcome. They think we can't bear the hanging consequence, the unanswered question, the open-ended denouement, the hopeful but ambiguous conclusion. But they'd be wrong.

We simply want an acceptable, believable culmination to the story that's been presented, an ending that is narratively logical, emotionally impactful, and authentically commensurate to the characters and plots the writers have created and we've been following throughout. Finales are not cliff-hangers, they are not whimsical contradictions to everything that's come before; they are not inexplicable departures from the foundation that's been set. At least a good ending, a satisfying finale. Those should not ask us to accept, for example, that the character -- the very real, human, flawed but endearing character -- we've been cheering on for seven years is really, at the end of the day, as unethical, as selfish and self-serving, as shallow and corrupt as the very people we've wished her away from since the beginning. To do that is to have served us a complex and delicious meal, only to inform us afterwards that it was concocted of dirt and straw...I don't know why I came up with that, but you get the point: it leaves a bad taste!

But writers are of many camps when it comes to endings. Throughout creative culture, with its myriad tastes and various zeitgeists, endings have swung from banal to maddening based on the mode of era. We've gone from the treacly Hallmark endings of the 50s, to the iconoclastic jolt of 60s/70s dramas with their non-conclusion conclusions and jarringly unanswered questions. In more recent years, films, TV, and books have come in a roller coaster of stylistic renderings, some offering the novelty of campy cop-outs, others struggling to deliver enough emotional punch to at least leave a mark, while a few just pull the plug, leaving audiences to walk away mumbling their disappointment.

It's perplexing, which is why, one presumes, so many incredibly good television series struggle with how to end what they've spent years creating, too many punctuating their masterpieces with underwhelming, surprisingly "meh" finales.

Certainly The Good Wife is not alone in letting down its audience; both The Wrap and The Rolling Stone remind us of a few other series finales that left us everything from wanting to outraged, from the black screen of The Sopranos to the religious mumbo-jumbo of Lost. So the question remains: why can't series creators land the ending?

The truth is, some have. Breaking Bad has to have delivered one of the truest, most congruent and audience-honoring finales of any series in existence. Certainly Cheers left its loyal viewers feeling satisfied and properly sent off. Six Feet Under took its delicate and demented storytelling on death to a profound and heartfelt conclusion. Meaning, it can be done... it just so often isn't.

Of course, it's all subjective. While I'm carrying on as a result of my clear disappointment in Alicia's slunk down the hall for the last time, someone else is formulating their thesis on why that slunk was the height of brilliance... what do any of us know?

What I know is this: I want to feel that the characters created have been concluded in a way that makes sense, that makes my involvement in their lives a worthwhile investment of my audience time. If you're going to give me a woman who's had to climb up from the depths of disappointment and despair, who's had to transcend a scummy, scheming husband to find her own footing and discover her own strength; if you're going to ask me to care about her, suffer with her, hope for her happiness and feel concern when she crosses the line; if you write her in such a way that compels me to cheer her success, to wish her well, to see her as someone who deserves my admiration and support, then don't leave me with that bad taste in my mouth. Don't leave me feeling that this character I've rooted for all this time has evolved into an empty, manipulative, misguided slave to her own ego. To do that to me, the audience, is to render the whole series, the whole arc of Alicia Florrick's character, as pointless as the empty mysticism of Lost, the chicanery of Bobby Ewing's death, and the bait and switch of how that guy married their mother.

A good ending memorably seals the deal. A bad one just... well, it just ends things.

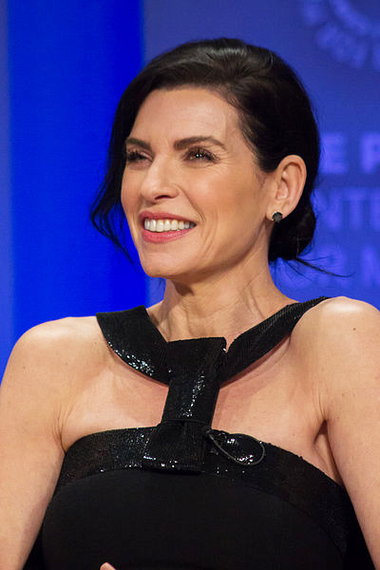

Julianna Margulies by iDominick @ Wikimedia Commons

___________________________________________________________

Follow Lorraine Devon Wilke on Facebook, Twitter and Amazon. Details and links to her blog, photography, books, and music can be found at www.LorraineDevonWilke.com.