Phil Ochs was already dead when I discovered him. He had killed himself in 1976, four years before I sat on the floor of the KOPN-FM community radio station in Columbia, Missouri, looking for music for my social change radio show. I found the music I needed and a lot more more.

Phil Ochs was already dead when I discovered him. He had killed himself in 1976, four years before I sat on the floor of the KOPN-FM community radio station in Columbia, Missouri, looking for music for my social change radio show. I found the music I needed and a lot more more.

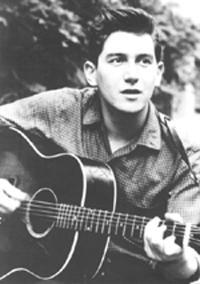

There are some voices in the world so distinctive and soulful that they feel like the home we didn't know we lost. The first times I heard James Taylor, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Bruce Springsteen, Greg Greenway, Tracy Chapman, Joni Mitchell, and Kelley Hunt, I felt like they were old friends I've known all my life and whose music seemed to know me also. Phil Ochs is part of that small circle of friends for me, but unlike what he writes about in his song, "Small Circle of Friends," his music doesn't turn away from the world's woes out of self-interest or apathy, but shows up with a fury. Jac Holman, founder of Electra Records, says, "Phil had what was essential: a stance, six strings, and an insistent voice wanting to be heard." Ochs' deep passion funneled through clarity, wit, and conviction transcends the sum of his considerable parts: a great sense of rhythm and verve in his songwriting, his vibrant guitar playing and picking, and most of all, his bell of a voice. Altogether, his music shines a spotlight on what's wrong in the world and how it could be made right.

Yet most people have never heard of Phil Ochs although, according to Robert Christgau, eulogizing Ochs in the Village Voice, "Not since Pete Seeger has there been a folksinger of Ochs's stature who could claim his unswerving opposition to political and economic oppression." Pete Seeger himself saw this from the get-go, telling us, after seeing Ochs and Bob Dylan in the early 1960s, "Here I am with two of the greatest songwriters in the world, and someday they'll be famous." What Seeger couldn't have known was that Ochs would kill himself at age 35 after years of limited fame, mental illness, alcoholism, and tidal waves of political heartbreaks. Ochs even parodied his lack of fame in his album, "Greatest Hits" because he never had any hits. Then again, nothing Ochs did was simple: he wore a gold lame suit, spoofing Elvis Presley, on that album cover, and said, "If there's any hope for a revolution in America, it lies in getting Elvis Presley to become Che Guevara."

His complexity was as legendary as his music. He loved John Wayne and cowboy movies, but grew up a music prodigy. He protested the Vietnam war but went to military school. He was smarter than most of his generation but dropped out of college. He sang of great tenderness in "Changes" and "Pleasures of the Harbor," but skewered bigots, liberals, and the apathetic in other songs. He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., but couldn't stand up for his own mental health. He played for any cause -- a homeless man on a corner in the Bowery to striking minors in Kentucky - but sought fame at great personal cost. He penned and performed one of the main anthems of the anti-war movement - "I Ain't Marching Anymore," but found little relief when the war actually ended.

On a personal level, his complexity was downright deadly. "Phil was never cool. He was right there, and exposed himself in a way that was ultimately lethal," said Sam Hood, manager of Greenwich Village's famed Gaslight club where Ochs, Dylan and many others performed in the 1960s. Growing up in Ohio with a distant Scottish mother, and an American father irreparably damaged by WWII and bi-polar disorder, Ochs followed music to New York just on the cusp of the 60s. He found his inspiration in the news, rather literally, turning news stories into songs, aptly naming his first album, "All the News That's Fit to Sing." He went onto to release more albums, played a sold-out Carnegie Hall, fell in love and had a daughter, and hung out with an infamous and inspiring group of radicals, artists, musicians, writers and organizers, from Joan Baez to Jerry Rubin.

Ochs' songs called for a new world vision of greater compassion, peace, honesty, concern and action. But he was soon caught between the rock of the times and the hard place of his brokenness. The public losses were immense: the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Dr. King, and Robert F. Kennedy; thousands of American soldiers and millions of Vietnamese dead or dying on the nightly news; the Kent State shootings; and the splits within various protest movements. Two particular historic devastations - one in Chicago, and one in Chile - especially affected Ochs.

In 1968, Ochs was one of the organizers of the Yippies' "Festival of Life," one of many demonstrations outside the Democratic convention. Ochs, after several performances, was caught in the standoff between peaceful protesters and Mayor Dailey's no-holds-barred police force, a clash that resulted in abundant bullets, teargas, beatings, and arrests. Ochs was so destroyed by what he experienced (including his arrest) that on the cover of his next album, he put a small picture of a gravestone engraved with his death happening in Chicago in 1968.

Three years later, needing a break from American politics, Ochs traveled the world. Along the way, he met "the Pete Seeger of Chile," singer Victor Jara. Salvador Allende had just been elected president, and Jara greeted Ochs as an international hero, taking him to sing for miners and even doing a Chilean television show together as the two men became fast friends. Ochs' paradoxical life continued to unfold in these travels: he was the first American singer to record collaborative music with Africans, weaving their traditional harmonies with his; during the same trip, robbers beat him so severely in Tanzania that they damaged his vocal cords. Already on rocky ground, Ochs descended further into drinking and paranoia.

By 1973, a coup forced Allende from power, and Jara, along with thousands of other activists, artists and musicians was brought to a giant stadium where soldiers tortured him and smashed his hands, then told him to sing. Jara stood up with bloodied hands and led thousands of other prisoners in singing the anthem of Allende's unity party. They were subsequently gunned down. When Ochs heard the news (as recounted by his friends in the excellent film Phil Ochs: There But For Fortune), he lost his mind, but he also regained some direction in organizing "An Evening with Salvador Allende," a benefit for Chile. While he was so drunk during the show that he could hardly sing at times, because of Dylan's participation, the benefit was a success and was also the first time people publicly announced that the CIA was likely behind the Chilean coup.

Besides truth-telling and coalescing people to march, sing, and fight for various causes, Ochs' contribution as a musician crossed into the absurd at times, or more accurately, Theatre of the Absurd, which he loved. He organized "The War is Over" events in 1967 (and wrote an amazing song of the same title), bringing together thousands of people to march against traffic with noise-makers to celebrate the end of the war. "You can create your own reality. This is what people forget when they become children of the media," Ochs said. By the time the war actually ended eight years later, Ochs was almost beyond reach when he performed for 100,000 in Central Park with Seeger, Odetta, Harry Belefonte, Baez, and many others. He would die by his own hand within a year.

"He was independent, and he took on whatever was ridiculous even he was ridiculous too, but he was ridiculous in a very decent way. He was really devoted to peace and justice," said his friend and fellow organizer Cora Weiss. What he left behind was a body of music precisely naming his devotions. As writer Christopher Hitchens said in There But for Fortune, "Phil's very tough grainy songs like 'Santa Domingo,' 'Love Me, I'm a Liberal,' and 'Here's to the State of Mississippi' were far more political and tough-minded that the much more generalized accessible 'Blowing in the Wind.' Anyone could like Bob Dylan. Everyone did."

In 1980, I held Ochs' albums in my hands, listening to every lift of his beautiful voice and true note of his guitar. In February of 2016, I joined a big crowd in Lawrence, Kansas for "A Night with Phil Ochs, a concert organized by West Side Folk that featured Zachary Stevenson, a young actor and singer who completely embodied Ochs in voice, gesture, patter and manners. Stevenson reminded me of what I had missed in never seeing Ochs live, and the crowd - singing, laughing, crying throughout the charged concert - showed me what a difference Ochs made to those of us who had heard of him as well as how important it is to share his legacy.

"There's no place in this world where I'll belong when I'm gone," Ochs wrote in another anthem-like song, calling on us to take action and live vividly when we're here. Although Ochs is long gone, his words and songs still belong. The racism, economic disparity, greed, corruption, police brutality, and other cracks in the world Ochs wrote of are still tearing us apart and calling on us to summon up what Ochs also sang about: tenderness, awareness, and action, and most of all, courage.

More on Ochs: Check out many videos of Ochs performing youtube, through his sister Sonny Ochs' remembrance page , the film Phil Ochs: There But For Fortune, a book of the same title by Michael Schumacher, and wherever else you can find him. Most of all, listen to him singing of a world we still seek.