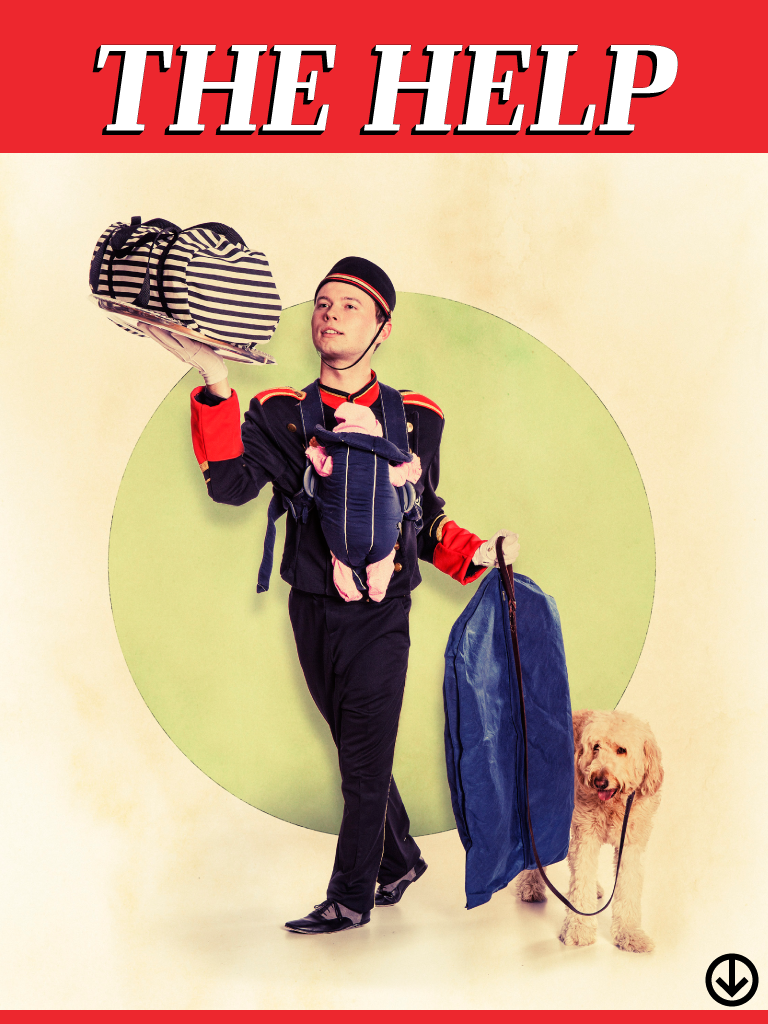

(Illustration by Stephen Webster)

Amanda Jones, a real estate agent from San Francisco, toured her house one day last month and counted the number of people she was paying to take care of her. There were seven.

April, the dog walker, was in the kitchen picking up Speedy and Willis – Jones’s miniature dachshunds — for their $35 walk. Up in the master bedroom, Christina, Jones’s $50 an hour closet organizer was strategizing with Jackie, her $200 an hour personal stylist, about what to buy at the Container Store (Jackie’s assistant was there, too, built into the hourly rate).

Meanwhile, two men were installing new windows in Jones’s bedroom, but she hadn’t hired them herself — she hired someone else to hire them. They came with rave reviews from Carrie Starner Keenan, a lifestyle management concierge who coordinates home contracting projects, plans events and secures the most elusive reservations at the best vineyards in wine country for $75 an hour.

“I turned to my assistant and said, ‘It takes a village,’” recalls Jones, who has a separate personal assistant to take care of work-specific matters.

“It’s kind of crazy but I feel like I need these things because I’m not going to sew a button on a shirt, and I’m not going to spend a weekend organizing my closet.”

People like Jones, with little time and plenty of money, have seen their options increase of late when it comes to personal providers, otherwise known as concierges. The line of work once specific to the hotel industry is now offering hyper-individualized services in industries ranging from home contracting and fitness to pets and pregnancy.

And with these services comes a new mentality toward the help. They aren’t just following orders anymore. They’re taking the lead, sometimes guiding their employers’ most important life decisions — even something as personal as raising a child. In the same way a hotel concierge can plan every day of your trip to a new city, a maternity concierge, for example, can plan out a pregnancy with suggestions for a birthing plan and which baby products to buy.

Indeed, it does take a village — but it will cost you.

Altogether, Jones estimates that she pays anywhere between $2,500 and $5,000 a month contracting out aspects of her life that she’d otherwise neglect. Paying to have other people deal with unpleasant tasks helps to mitigate the “always-on mentality” that her job requires, and that constant e-mailing only exacerbates.

“I don’t think we can underestimate how technology has changed our lives, just changed everything about how we spend our time, how we think about our time,” says Jones.

Because she often works seven days a week and can’t predict her schedule, Jones thinks of the army of people helping her out as contributors to her success. The money she pays Starner Keenan to set up a catered outdoor lunch on the terrace of a property she is trying to sell, for example, might help to win over prospective buyers. On top of that, each of the services that Jones uses provides her with something invaluable: time.

Amanda Jones, center, and her concierge Carrie Starner Keenan, third from right, surrounded by Jones' team, including the dog walker, assistant and closet organizer. (Photo by Gabriella Hasbun)

“I think people are looking into things that are going to allow them to be more efficient, and that’s how I feel. I am so much more productive when the personal things in my life are handled,” says Jones. “I’m going to pay $50 an hour for the closet girl and $200 an hour for a stylist. But I’m not going to spend time roaming around Barneys and Saks on my own being sold things by a commission based sales person.”In line with many business sectors pushing luxury items and non-essentials, the concierge industry was hit hard by the recession. According to a recent report by the research firm IBIS World, industry revenue dropped 6.2 percent in 2009, with demands from both corporate clients and households declining. By the end of 2012, industry revenue is expected to total $220 million. But over the next five years, IBIS expects the concierge industry to see an uptick, with annual revenue projected to grow to $264 million for 2017.

“Some factors that have really contributed to growth is decreased leisure time among individuals,” says Caitlin Moldvay, a senior analyst with IBIS. Moldvay notes that according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of 2010, the average American was limited to 5.2 hours of leisure time per day, with two of those hours going towards household activities.

The IBIS report also predicts that people making more than $100,000 a year — the industry’s primary targets — will see their incomes improve in the coming years along with the economy, and that they’ll have more discretionary funds as a result. Demand in the concierge industry, according to IBIS, is directly tied to the number of people with disposable incomes. So indicators show that this arguably superfluous industry will only strengthen over time, despite a flagging economy.

As over the top as such expenditures are, fans of hiring concierges consider them somewhat practical purchases: in the long-run, people argue that through concierges, they’re saving time, work and even bettering their overall health and well being.

While having services tailored to one’s individual needs is no doubt a luxury that’s out of reach for most people, the same reach for outside help has translated to lower income brackets. Some in the industry have identified a more affordable market for people willing to pay someone else to do things for them. With the emergence of more virtual assistant services, even those outside the 1 percent are getting some taste of what it’s like to have hired help.

In both the concierge and virtual service industries, what’s slowly emerging is a new relationship between ‘the help’ and the helped, so to speak. Instead of simply following orders, they’re taking charge of some of the most intimate parts of their employers’ lives.

“TARGETED MONEY”

Katharine Giovanni, founder of the International Concierge and Lifestyle Management Association, estimates that in 1998, there were only around 50 individuals offering concierge services outside of hotels nationwide. Around that same time, Giovanni was launching her own concierge business and collecting information as she researched what the industry already had to offer.

Giovanni says it was hotel concierges who started offering their services to non-guests that pioneered the independent concierge industry. Those concierges simply took what they were already doing — like making reservations or getting tickets — and started doing those tasks for other people. Eventually, some of them started their own businesses. Today, there are hundreds of concierges serving every niche imaginable.

“I know a concierge who is specializing in the patients of plastic surgeons,” says Giovanni. “If you’re a patient and you just had a facelift, you certainly don’t want to go out to the grocery store.”

Giovanni admits that the concierge industry as a whole is still climbing out of the recession, with association membership numbers dropping by 40 percent as recently as 2011. But Giovanni says that those numbers have started to rebound this year as a consequence of Americans being busier at work.

“Everybody on the planet is trying to squeeze 36 hours into a 24 hour day,” says Giovanni. “I don’t care what the economy is doing, that’s what’s happening. And when you do that, inevitably you don’t do it very well.”

Giovanni has a term for the currency flowing toward the concierge industry: “targeted money.”

“People who have the money to spend are saying, ‘I’m going to spend targeted money. So what means the most to me? Spending more time at the office or spending more time with my kids?” she says.

Starner Keenan, the lifestyle concierge who found the good window guys for Jones, says she’s already seen signs of increased demand in terms of the number of clients she is working with. At the same time, there’s been a subtle shift in how some of her clients are spending money, which she links to the recession.

“Even my very, very wealthy clients, everyone took a moment and stopped and really reassessed their spending. I think a lot of people were very nervous,” says Starner Keenan.

She says the cautionary mood hasn’t reduced her business, but rather made her clients more practical, and thoughtful, in their spending, going after value-based services. They might ask her to develop a plan to make their homes more eco-friendly, incorporating solar panel floors to save on operating costs. Other requests include having her shop around for bids from contractors to get the best deal on a remodeling project that will eventually increase a home’s value.

“It’s not 100 percent value-based,” admits Starner Keenan, “I get some really fluffy requests, but these are busy people and they don’t have time to get things handled.”

For Julia Dalton-Brush, 33, of Manhattan, practical spending means putting money towards personalized fitness. She recently started paying $150 a month for a fitness concierge and says that the service is worth it by ensuring that she actually works out.

As a former college athlete, Dalton-Brush used to exercise on a regular basis. But since becoming a mother and a business owner, she’s gained 70 pounds, which is why she hired Vanessa Martin, the fitness concierge behind SIN Workouts.

“It’s a luxury service, there’s no doubt about that,” says Dalton-Brush.

Contrary to what one might expect, a fitness concierge is different from a personal trainer. They function not as coaches so much as secretaries, scheduling clients’ fitness routines, and occasionally coming along for the ride. Martin, 27, launched her business in August after recognizing the need for her expertise in managing the boutique gym circuit, which includes studios like FlyWheel, SoulCycle, Barry’s Bootcamp and Pure Yoga.

“It’s kind of a daunting process to get into some of these prime-time classes,” says Martin, who started out by managing the workout schedules of her friends. “They would ask me, ‘What instructors are good? How early do I have to get there?’ It comes down to the basic things of, like, what do you wear to a spin class?”

Martin refuses to disclose her fees, or even a range, claiming it’s impossible to know what any hypothetical client would have to pay because her services are just that individualized. But all the clients Martin works with have enough money where they don’t need to budget for her services. Many of those clients are friends of friends who pay three digits a month on top of their gym costs.

In exchange, Martin might create a personalized regimen, make wake-up calls, or have a car service outside a client’s door in the morning. She also might take classes alongside her clients.

Fitness concierge Vanessa Martin for SIN Workouts makes sure her clients don't skip their cardio. (Photo by Laura Barisonzi)

One rainy Friday morning last month, for example, Martin and Dalton-Brush met in Chelsea and took a 9:30 a.m. circuit training class at Barry’s Bootcamp, followed by a 10:30 a.m. spinning class at FlyWheel.

Classes at Barry’s and FlyWheel feature marquee instructors at the front of the room, so Martin’s presence is supplemental: she might tweak a client’s form if need be, but on this day at least, she functioned mostly as moral support by running on the treadmill next to Dalton-Brush and shouting out the occasional, “Woo!”

“Now I’m being held accountable,” says Dalton-Brush. “It’s definitely a cheerleading thing.”

If Dalton-Brush wasn’t scheduled to meet Martin at Barry’s that morning, she says there’s a good chance she would have dropped off her 4-year-old at school, walked right back home to her apartment and wasted the money by not showing up for a class she’d already paid for.

CHOICE OVERLOAD

Before first time mother Maria Campos-Yatzkan, 42, gave birth in August, she was willing to pay for the peace of mind that came with having a maternity concierge from a local store called Tutti Bambini plan out her registry.

“It prepares you and saves you time, and probably money as well,” says Campos-Yatzkan. “If you don’t have experience, you could buy certain bottles that are not good for the baby.”

Campos-Yatzkan, who works as a physician, is unsure how much money she spent at Tutti Bambini before giving birth, because in addition to hosting her shower and designing her registry, the company designed a nautical themed nursery for Campos-Yatzkan, a surprise gift from her husband.

Monica Burgos-Valdes, the executive baby planner at Tutti Bambini, says that the year-old maternity concierge operation has brought in about 25 clients so far. The market extends beyond the borders of well-heeled cities like New York. Melissa Moog, with the International Baby Planner Association cites members who are running their own maternity concierge and baby planning businesses in 20 different states.

An elegant baby shower set up by Tutti Bambini. (Photo courtesy Tutti Bambini)

For $75 to $115 an hour, Burgos-Valdes finds nannies, night nurses and lactation consultants, all the while planning baby showers, designing nurseries and telling parents which products should be avoided due to recalls. Her clients, she says, tend to be “working moms” who “don’t have time for all the little things that having a baby encompasses.”

By extension, these mothers are putting substantial trust in their service providers, and in the idea that paying a high enough price will guarantee them the best stroller, the best baby proofing services for their homes, or even something as crucial as a nanny referral.

In much the same way that people of a certain means are willing to spend top-dollar on their children, Mitch Marrow who runs a pet day care service, is working off of the concept that they’ll do the same for their pets. He recently launched a pet concierge service in 30 luxury apartment buildings in Manhattan, with the operating principle that no perk is too expensive to incorporate.

“It’s not a dollars and cents type of relationship with our customer base,” says Marrow, a former NFL player and owner of The Spot Experience.

For monthly fees starting at $400 and going all the way up to $1,500, residents can choose from a range of packages that might include shuttles to and from daycare and GPS monitored walks with a trained employee who has been through a criminal background check.

NOT JUST THE 1%

According to Melissa Hobley, a representative from the marketing firm Buyology, such extravagant offerings are a new expression of the American corporate tenet of customer service. As a result, she says, the concierge model is spreading upwards. Last spring, Lincoln, the luxury car division of Ford, paired with an international concierge association.

To counteract the allure of the internet as an easy resource for people in the market for a car, Lincoln now has some of its employees trained by hotel concierges to offer a higher level of service. Virtual concierges are also on call 24 hours a day to offer online tours of vehicles and answer questions from customers.

“It’s not terribly surprising in a digital age,” says Hobley. “It’s become so hard for a company to build a relationship with you.”

In a similar vein, finding just about any goods or services online these days can be overwhelming, Hobley says, thanks to the deluge of offerings on the internet.

“We’re just overwhelmed by information,” says Hobley. “People will pay to whittle down 200 choices down to 20.”

The twist here is that the hired help now tell their bosses what to do. Clients are willing to have less power over certain aspects of their lives, because it’s easier than doing it themselves.

“This is why it kind of matters that you have some faith in the concierge, who is your proxy, to make the decision for you,” says Rachel Sherman, a professor of sociology at the New School who has studied concierge providers. “If you want your concierge to give you 10 options, you are sacrificing seeing the other 500 options that the concierge is going to look at.”

Whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, Sherman says, may depend on the individual client and how much they care about sacrificing choice versus spending time. Through their marketing, Sherman says, service providers try to circumvent the idea that handling tasks yourself has an inherent value.

“The research that I did indicated that the more general lifestyle management concierges are being sold as a way of outsourcing the parts of your life that are not rewarding to you. They’re always saying, ‘We do what you have to do you, so you can do what you want to do.’ That’s a very frequent tag line you see,” says Sherman.

Ariana Massarat, 30, who works in business development for AT&T, started paying for a virtual assistant three months ago to help plan her wedding after finding a deal on a flash sale website for a company called Fancy Hands. Since then, Massarat has had assistants booking appointments at venues, and sorting through reviews online to find the most reputable people to handle hair, make-up and flowers for the big day.

“It really just frees up some of my time so that I can actually focus on my fiance,” says Massarat.

Fancy Hands, which launched in 2010, joins the ranks of what’s become a popular business model. Red Butler, for example, offers similar services and they’ve been around since 2005. But they’ve seen more industry competition in recent years from other virtual assistant services.

Nick Ramirez, a vice president of business development for Red Butler, says demand for reasonably priced online personal assistants to handle errands and menial tasks has been growing.

“We’ve actually increased staffing,” says Ramirez. “We’ve hired more concierges.”

Customers pay less for these types of concierges by virtue of the fact that requests are usually handled over email, and that a rotating cast of characters might be helping them on any given day. TaskRabbit, for example, which launched in 2008, pairs people looking for errand-runners with vetted local service providers online. Customers can name their own price and service providers then bid on the task.

Ted Roden, the man behind Fancy Hands, uses the tagline “Assistants for Everyone” on his website. Roden is making an effort to appeal to people who want to have a personal assistant, but can’t afford one.

A $25 a month membership gets customers five requests that can be as specialized as they want, and $65 a month buys 25 tasks. Roden says his assistants have fired off lists of the best Twitter accounts for Broadway reviewers and ordered flowers for wives on behalf of their husbands.

Roden says he knows from his tracking system that his company’s assistants are already logging more than 24 hours each day on the phone fulfilling tasks for wits customers.

“I’ve heard people say this kind of business is for the 1 percent,” he says. “We’re breaking down that wall.”

According to Sherman, services providers marketing to those outside the 1 percent often try to make their clients in middle income ranges feel like they’re entitled to contract out errands and personal tasks, as opposed to selling them as a luxury.

“It encourages people to think that there are certains kinds of things that they’re not doing for themselves anymore, just like when you first hired someone to clean your house,” says Sherman, the sociologist. “It creates a hierarchy of tasks, some of which are appropriate to pay people to do, and some of which are not.”

Eventually, that mentality might start to become normal for a consumer, redefining what we consider personal enough to

do ourselves.

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.