Halloween is the longest-running holiday ever in the history of the world, except for Take Your Pet to Work Day. Halloween culture can be traced back to the Druids, part of the Celtic culture. The Celts were a squirrelly lot. They had no central government, no big important person in charge of everyone, no elected representatives or even Neighborhood Watch. They were a loose confederation of tribes with different languages, customs, and teacher work days.

In spite of this amazing lack of organization, they seemingly popped up out of nowhere around 400BC in northern Italy and displaced the Etruscans from the fertile Po valley. The Etruscans, who had some really cool pottery, architecture, and art, just sort of gave up and disappeared. The Celts ultimately spread all over the place, especially the British Isles.

The Druids were the members of the educated, professional class among the Celtic peoples. They were at the top of the heap of Celtic society, and had a lot of responsibility. They worked hard and obviously needed a break. Because neither the Aspen nor Dubai had yet been invented, they created the feast of Samhain (which isn't pronounced anything like you think it is, so don't even try). Samhain, held annually on October 31st, was a harvest festival with huge sacred bonfires, marking the end of the Celtic year and beginning of a new one. The end of the year was when dead people came back, most likely to collect debts before the end of the fiscal year. So the day also included a celebration for the departed.

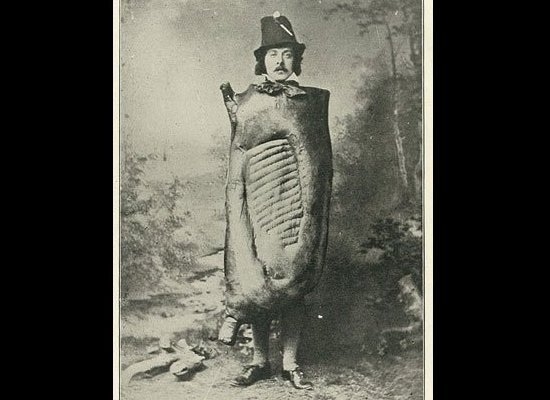

The truth was that Samhain was a thinly veiled excuse to dress in costume, eat bad food, and get drunk. By 43 AD, Rome conquered Celtic lands. The Romans were smart cookies, and didn't obliterate Samhain. Instead, they threw their own harvest festivals into it, added apple bobbing, and everyone continued to party down.

By the ninth century, the Catholic Church took over all Celtic lands. The Church, as most people know, was not filled with Fun People. Instead, they had things like randy popes, wealth, and unlimited power. The Church took a quick look at Samhain and decided it looked like far too much fun to allow it to belong to the Celts and Romans. They wanted it for themselves.

In 1000 A.D., the Church made November 2 All Souls' Day, a day to honor the dead. All Souls Day was clearly a new power in the hood. It was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils. It was still Samhain, but now brought to you by the Catholic Church.

The All Saints Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints' Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween. Thus was Halloween born.

Protestants made Catholics look like a bong party on Fraternity Row, so Halloween did not translate too well to Colonial America. But it didn't die completely. New ethnic groups and Indians kept it going. Celebrations continued, and included eating and telling ghost stories. After 1850, immigration, especially that of the Irish, saw a boon in Halloween celebrations. Americans began to dress up in costumes and go house to house asking for food or money. Sometimes, they actually needed it. Young women believed that on Halloween they could divine the name or appearance of their future husband by doing tricks with yarn, apple parings or mirrors. Today, that has been proven to be more successful than internet dating.

In the late 1800s, there was a move in America to mold Halloween into a holiday more about community and neighborly get-togethers than about ghosts, pranks and witchcraft. Halloween parties for both children and adults became the most common way to celebrate the day. Parties focused on games, foods of the season and festive costumes. Parents were encouraged by newspapers and community leaders to take anything "frightening" or "grotesque" out of Halloween celebrations. Because of these efforts, Halloween lost most of its superstitious and religious overtones by the beginning of the twentieth century. It also became way less fun.

Despite the best efforts of many schools and communities, vandalism began to plague Halloween celebrations in many communities during the first half of the twentieth century. By the 1950s, town leaders had successfully limited vandalism and Halloween had evolved into a holiday directed mainly at the young. The birth of baby boomers cemented Halloween as a holiday for children. Trick-or-treating was also revived.

Adults, now sidelined from a holiday they started, began to gather on the streets and in the bars of major cities, wearing Naughty Nurse and Devil outfits. The average Halloween reveler had no idea that Halloween was anything more than a day to celebrate the liquor industry.

Today, Americans spend an estimated $6 billion annually on Halloween, making it the country's second largest commercial holiday. Costumes are clever representations of political events and notable people of the past year, as well as vehicles in which to display cleavage and legs. Americans' love for their children is manifested by sending them out in the dark to knock on strange doors and force-feeding them vast amounts of sugar.

Boo.