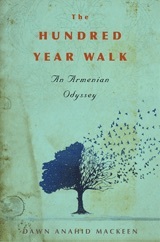

In 2007, Dawn Anahid MacKeen quit her magazine job in New York to write about her grandfather's persecution and unlikely survival of the Armenian Genocide. Using her grandfather's journals as her guide, MacKeen traveled to Turkey and Syria and retraced the 900-mile death march her grandfather made with thousands of other Christian Armenians. In Syria, MacKeen found the descendants of the Muslim family that saved her grandfather's life. Her book, The Hundred-Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey (Houghton Harcourt Mifflin) is a combination memoir and meticulously researched, riveting account of her grandfather's almost unimaginable ordeal.

Lyrical, haunting, moving, and unforgettable, The Hundred-Year Walk both underscores the harsh realities of the Armenian genocide and illuminates the deeply transformative power of human kindness, forgiveness and love.

I met with Dawn Anahid MacKeen at her home in Southern California to talk about The Hundred-Year Walk.

How did you decide to write a book about your grandfather's remarkable survival during the Armenian genocide?

I grew up with the story. My mother would tell me about it on any occasion--during breakfast, or dinner, or a birthday party. She would always steal a moment to talk about what happened to her father, about how he'd crossed the desert without any water and was so thirsty he had to drink his own urine. I couldn't fathom a situation in which someone would be forced to do that. Because my grandfather died when I was a kid, I didn't know much more about him than that. To explain, my mother would point to her father's firsthand account, which was published as two small booklets in the 60's, and say "It's all in there." But I couldn't read it because it was in Armenian. After a relative translated it, I could read it for myself, and could finally understand the scope of what he endured.

As I turned the pages, I just could not believe that this endangered protagonist was my own grandfather. You know when you read a story of someone who is in danger and you are biting your fingernails and pulling up a blanket to kind of protect yourself? I was doing that. With each harrowing moment, I would wonder what was going to happen, and then it hit me: "If he doesn't make it through this situation, I wouldn't be here." And neither would my mother, my uncle, my aunt, my cousins and so forth. It's really unbelievable that a century after these atrocities occurred, Turkey still does not acknowledge it. I felt that I had no choice but to tell this story.

Your grandfather's survival was extraordinary. Reading The Hundred-Year Walk, even though I knew--as you said--that your grandfather would ultimately survive I kept getting to parts where I thought, "How is he going to pull through this?" Could you talk a bit about some of the obstacles he faced?

He faced Turkish gendarmes forcing him into a death march, and watched them kill the people who lagged behind. He faced extreme starvation--days without food--and when he finally found food, such as a rotten apple core or a watermelon rind, it was something to be celebrated. He suffered through real physical hardship; he'd been so thirsty he foamed at the mouth, and also faced an extreme test of his emotional limits. At one point, he was so defeated, he believed that dying would be a relief. But he overcame that; he was determined to see his family again, which is really what the book is about. It's about genocide, but in the end this book is about family. It's about my grandfather wanting to see his family again. It's about him telling my mother about what happened to him, and her passing on that story to me.

One thing I loved about the book is that you show how your grandfather was always very resourceful, entrepreneurial, very much a prankster, scrappy, and how that history of his personality had been erased, because genocide erases the memory of those aspects of a person's personality and all that is remembered is their suffering. But in the book you really bring through not only that he suffered, but also that he was a lovable, hardworking, amazing person. In learning his story you learned all that about him as well, which I thought was really beautiful.

Thank you. It was a surprise for me too to learn that side of him, that he was really mischievous. I wish I were friends with him. He was always pulling off little capers, whether speaking a made-up language in a crowd for fun, or summoning friends to a pretend meeting, with the surprise agenda of it being an ice cream social. It was wonderful to get to know that side of him.

Your book is both a history book and a memoir since you alternate between your grandfather's story and your own journey across Turkey and Syria as you retraced the path that he walked. You went to Turkey only a couple of months after the journalist Hrant Dink was gunned down while leaving his office after writing about the Armenian genocide. What was your experience in Turkey and did you feel the need to hide your reasons for being in there?

Yes. I did feel that I had to hide why I had traveled because of the political climate. Also, I was very fearful after hearing my mother speak about these atrocities my entire life. The issue was especially pitched when I arrived in 2007, not long after Hrant Dink's death. Writers were being prosecuted for insulting Turkishness. So at the time I was scared to speak out about it, but slowly I just started to tell people I was Armenian and that my family was from there. Most of the people were extremely kind to me, which I found surprising given the vitriol that often comes out about this issue. Even those I met who denied that the Armenian Genocide happened--which had made me so angry before the trip--I found to be kind people. They were just taught this other version of what happened in school, and consequently grew up believing it. To me, it all comes down to education.

But I think this new digital era is opening people's minds. All these alternative sources are now easily accessible online. I'm hoping those Turks who doubt what happened will seek out these sources, and read about what happened from a different point of view than the official state line. For example, the consular reports of Germany, who was the Ottoman's ally during WWI, is an incredible resource that documents the steady decimation of the Armenians from multiple eyewitnesses.

A Muslim family in Syria saved your grandfather's life. In the epilogue you write that one of the descendants of that family said that due to their recent experiences living in Syria during wartime, they now understand some of what your grandfather went through. Could you talk a little bit more about that?

When my grandfather escaped the massacre where almost everyone in his caravan was killed, he needed refuge. He heard about this Arab sheikh and decided to approach him. To blend in, he disguised himself by wearing a headscarf and traditional clothes. This sheikh was not fooled: he knew that my grandfather was a Christian Armenian and took him in anyway, despite the rhetoric he would have been hearing about the "dangerous Armenians." He stood up to hate, and took in a handful of other Armenians as well. My grandfather became like a son to this sheikh, and part of the community, working as a shepherd along the Euphrates. He really loved this clan. To me that was one of the most powerful aspects to his experience--that he had this bond that transcended religious and ethnic difference.

When I retraced my grandfather's footsteps to Syria, I found the descendants of this sheikh, and they were just as incredible and kind to me as the sheikh was to my grandfather. Nowadays, with the Syrian war, these people are undergoing extreme hardship. It's people like this who are flooding Europe and need refuge now. Most Americans had never heard of Raqqa, or the towns in eastern Syria, until the Islamic State took over. Now all they know of this area is this message of hate. I think it's important to remember the civilians living there are beautiful people like this clan. I worry about their safety on a daily basis.

Turkey still hasn't acknowledged that the Armenian Genocide took place. And likewise the United States government--not wanting to upset Turkey, a geopolitically important ally--has also failed to call the slaughter of 1.5 million Armenians a "genocide," instead using terms such as "mass atrocity" and "terrible carnage." Do you think it's important to call what happened "genocide"?

Yes, I do think it's important. I think everything else falls short. This was an extermination orchestrated by the government. This was the willful destruction of a people. Calling it a "massacre" is not enough. It was a genocide. Armenians want it acknowledged so we can heal and move forward. I think what Pope Francis said last April on the 100th anniversary of the genocide rings very true: "Concealing or denying evil is like allowing a wound to keep bleeding without bandaging it."

I think it's come the time to acknowledge, to educate, and to forgive.