"The Hunt for KSM: Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed" by Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer (Little, Brown, $27.99) describes itself as the "definitive account of the decade-long pursuit and capture of the terrorist mastermind of 9/11." Drawing on unprecedented access to hundreds of sources, and investigative reporting across different continents, it provides a unique insight into the worlds of counter terrorism and espionage. In this excerpt, we learn about how KSM was finally captured - and the real story behind his famous photo.

Rawalpindi, Pakistan, Spring 2003

KSM was far more careful than most of his comrades about operational security. He seldom risked exposing himself. Others wired money on his behalf. He used cutouts for critical communications. Others sent and received e‑mails for him. He seldom wrote anything down, believing that important information was better delivered face‑to‑face. When he did write, the language was allusive. Other operatives succumbed to the allure of the quick and easy sat-phone call. Just one call, just this one time. Then they were targeted, caught, and taken off the field of battle.

One group of Arab fighters had been captured on the run because they kept going outside the house they were hiding in to smoke cigarettes. They couldn’t help themselves. They wanted smoke breaks and took them, often outside.

Neighbors eventually became suspicious, a team was dispatched, and they were taken away. KSM was irate. He lost not just the fighters but their safe house and several others, as well as the man who arranged them.

As time went on and more and more of his associates were captured, KSM relied even less on modern communications. “These guys were lying low. They were not using electronics. They were not being detected by electronic eavesdropping,” an ISI officer said. KSM instead sent trusted personal couriers. Others could cast their fates into the ether, where electronic detectives roamed. He stayed down on the ground, in the very human muck that was Pakistan. So in the end it was almost inevitable that it was a human who would betray him.

For more than a year, the CIA had been cultivating an asset who had contacted the agency out of the blue. The man was a longtime acquaintance of KSM’s. Mohammed’s family thought they might have met as far back as the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan. He was from Iranian Baluchistan, as was KSM’s family. They might have been distantly related, perhaps not, but were fellow Baluch—an extremely strong tie—in any case.

The agency was patient in cultivating the walk-in, whom we’ll refer to here as Baluchi. He spoke Dari, a dialect of Farsi, the principal language of Iran. The CIA had very few Farsi speakers accomplished enough to communicate with Baluchi. His initial handler was an Iranian American agent who was posted elsewhere overseas and flew to Pakistan whenever Baluchi or he wanted to meet. He was vetted over many months, and had passed polygraph tests. He seemed to be the real thing, maybe even capable of doing what he offered—delivering KSM.

Baluchi was paid regularly and provided useful information from time to time. The money was delivered to him in cash during his meetings with his handler. Fewer than a handful of the agency’s burgeoning Pakistan staff were allowed to know the man’s identity, or his purpose. The case was being run directly out of Langley under what were referred to as “restricted handling” rules, which mainly meant limited exposure on a strict need-to-know basis.

When his case officer left the agency in 2002, his new handler—we’ll call him Gino—also flew into the country just to meet with him. The Islamabad station residents were responsible for arranging safe houses for the meetings and sometimes for delivering money—thousands of dollars in bills in a paper bag—but they were not invited in to meet him. One agent caught a glimpse of him through a crack in the door at a safe house, sitting on a bed. He looked short and somewhat frail, much like virtually every other Baluch of his age and economic stature.

Baluchi sought to reconnect with KSM in person for months. The agency devised a plan to lure KSM to him; the bait was information that agents fed to Baluchi, who in turn passed it on to KSM. Finally, in late February of 2003, KSM agreed to meet Baluchi in Rawalpindi, a military garrison town southwest of the capital, Islamabad. He didn’t tell Baluchi the precise location, but said it would be that night, February 28. The CIA readied an attack team, made up primarily of its own agents and select members of the ISI who were not told whom they were going after. The FBI was not invited. The Americans still didn’t know where or if the meeting would occur, and they didn’t tell the Pakistanis the name of the target.

Marty Martin, the voluble head of the agency’s Sunni Extremist Group within the Counterterrorist Center, couldn’t contain himself at the 5:00 p.m. meeting of the executive staff gathered around George Tenet’s conference table on Friday. “Boss,” he said to Tenet. “Where are you going to be this weekend? Stay in touch. I just might get some good news.”

Aside from information about bin Laden himself, there could be no bigger news. KSM had risen dramatically in the agency’s estimation from the days when—except for assigning a single agent in the minuscule Renditions Branch to the task—they couldn’t really be bothered to track his whereabouts. Since then, so much effort had been spent with so little result that a potential breakthrough had begun to seem far-fetched.

KSM had been on the road with his nephew Aziz Ali and had met with Al Qaeda’s number two, Ayman al‑Zawahiri, the day before, near Peshawar. He arrived at the Rawalpindi safe house, a private residence, by car at about 9:00 p.m. The home, a large, comfortable, single-family residence at 18A Nisar Road in the Westridge district of Rawalpindi, one of its nicer areas, was owned by a prominent local couple. The husband was a scientist; the wife, Mahlaqa Khanum, was a politically active supporter of the Jamaat‑e‑Islami, Pakistan’s largest religious political party and one that had suspicious ties to Pakistani militant groups and even Al Qaeda. The couple claimed utter innocence later, but Mustafa al‑Hawsawi, the Al Qaeda accountant, had been in the house since January. Baluchi was brought to the house not long after KSM arrived. They talked for more than an hour. KSM, who was vigilant about the use of cell phones, for some reason allowed Baluchi to bring his phone into the house. Sometime later in the evening, Baluchi went into the bathroom and quietly texted his agency handlers: “I am with KSM.”

Not long afterward, Baluchi left the house and, once he was by himself, contacted the CIA agents again. This time, he knew how to bring them back to the home. After taking them there, Baluchi was quickly bundled off to the Islamabad airport by CIA officials, who put him on a plane. He was in the air and on his way out of the country before KSM even knew he was in danger.

The attack team took up positions outside 18A Nisar Road. By this point, the Americans and Pakistanis had cooperated on scores of similar raids, several of which were aimed at capturing KSM. This was, in that respect, just another day at the office. The team waited outside in the dark until it felt certain that KSM, a night owl, would be asleep.

The team waited until past 2:00 a.m., then the Pakistanis broke through the gate, through the front doors, and charged through the house, herding the family into a back bedroom. They found KSM sound asleep. They encountered only minimal resistance. KSM, groggy from an apparent dose of sleeping pills, offered to pay his Pakistani attackers to let him go free. When that failed to move them, he asked them if they’d like to cross over and join his team. “Why are you doing this for the Americans?” he asked. “If it’s money, we’ll give you what you want.” That didn’t work, either. KSM, al‑Hawsawi, and the owners’ adult son, Ahmed Qadoos, were taken into custody and spirited away.

Later, the legend of KSM’s capture would grow. There were tales of how he boldly wrestled with his pursuers, grabbed a Pakistani security agent’s rifle, and shot one of the Pakistanis in the foot before finally being subdued. It was said that when the authorities burst in he yelled, “Don’t shoot, there are women and children here.”

But the reality of it is that, in the end, KSM was caught completely unawares, and in his pajamas.

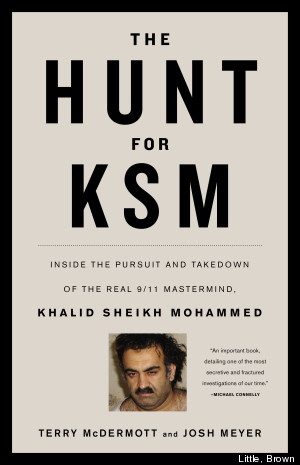

Marty Martin woke George Tenet with a phone call in the middle of the night. Tenet was at Camp David for weekend meetings with President Bush and his senior advisers. There was enough of a ruckus raised during the attack that neighbors were awakened, and the local media swarmed to the scene the next morning. The Pakistani government was forced to respond and acknowledge that three men had been taken into custody; one of them seemed to be a high-ranking Al Qaeda officer. By noon, the Pakistani press was reporting that KSM had been captured. The accounts varied wildly, but the fact of Mohammed’s capture was central to them all. Many ran photographs of KSM taken from wanted posters. Several of the photos showed him as a handsome, rugged young man. One pictured him in a Western coat and tie.

Back at Langley, Martin saw these early press accounts and was distressed at the accompanying photos. “Boss,” he said to Tenet. “This ain’t right. The media are making this bum look like a hero.” He asked Tenet for approval to release a somewhat less flattering photograph. Tenet agreed. A member of the CIA team had taken photos of KSM right after his capture, including one in which he looks into the camera, with his eyebrows raised nearly to his hairline. Still, Martin thought, that initial photo did not make KSM look sufficiently unattractive. Martin asked if there were any other photos available. The agent messed up KSM’s hair and then took another photo. The result was the famous image of KSM—thickset, glowering, wild-haired, half dressed in his nightshirt—his first introduction to most of the rest of the world.

Excerpted from "The Hunt for KSM: Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed" by Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer (Little, Brown, $27.99)