I do not know where the impulse to travel comes from but I have always had it bad, ever since I was four or five.

A Vietnamese child living in the Mekong Delta, I remember listening to my French-educated father's stories of snow -on the gilded bridges across the Seine; in the well-groomed parks of Paris; across his bunker's window when he was a military exchange officer at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and on barren trees and moss-strewn rock gardens and temple roof-tops of fabled Kyoto.

I remember standing on tiptoe on a chair next to the opened fridge with my hands in the freezer compartment scraping at the frost until my fingers were numbed. Even then, with eyes closed and a modest snowball in my palm, I had begun to travel; or perhaps I was trying to commune with my worldly father.

Then the Vietnam War ended and my family and I crossed the Pacific Ocean on a C-130 cargo plane filled with many crying refugees. I was 11 but, strangely enough, I did not cry. I had never been out of the country before, never crossed the ocean.

If I was witnessing the end of an important chapter in Vietnam's history, I could not grasp the significance of the moment.

Instead, I was mesmerized by my own transparent reflection on the plane window, my face super-imposing itself on the bright and extraordinarily beautiful horizon, lips slightly parted where the sky kisses sea.

Bruce Chatwin, the travel writer, once remarked that some crying babies could only be calmed down if they were carried and moved about, preferably in a car, because restlessness is a human impulse, something embedded in the gene. One becomes alive in movement, and every cell tingles with possibilities.

Travel stirs the imagination like nothing else. Away from home and hearth, ingesting in a new landscape, the traveller's concepts of his own identity, borders and nationhood are all up for dispute.

To travel, to really lose oneself in a new setting, is, after all, to subvert. In that C-130 full of refugees, I was moving not only across the ocean but also from one set of psyche to another. Yesterday, my inheritance was simple -the sacred rice fields and rivers, what once owned me, defining who I was.

Today, Paris and Hanoi and New York are no longer fantasies but a matter of scheduling. My imagination, once bound by a singular sense of geography, expanded its reference points across the border towards a cosmopolitan possibility.

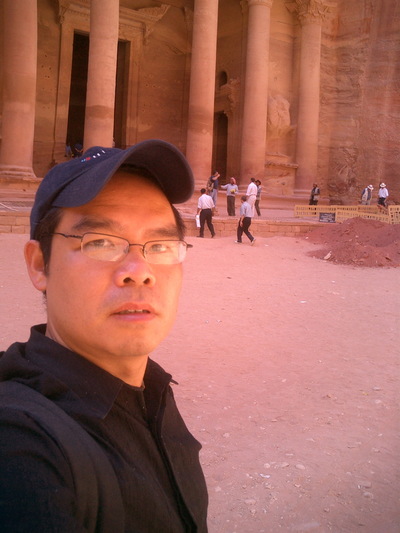

The Author gave talks in Cairo, and visited the pyramids in Nov. 2013.

INDEED, we live now at a time when freedom of movement is recognized as a basic human right and the business of travel -hotels, transportations, tours, cruises, restaurants, conferences -has evolved to become the largest industry in the world. Tourism since the Cold War ended is on a steady rise.

It is the No. 1 source of foreign revenue for many countries (including the United States), employs over 200 million people worldwide -about one in nine of all workers -and accounts for 11 per cent of all consumer spending.

Swift flow of information and borderless economies may be fusing globalisation but the phenomenon is created in large part by the unprecedented movement of people.

Here, in San Francisco where I now live, the international airport saw more people going through it last year than there are people living in the state of California.

Every day, cable cars climb up and down the street fronting my house on Nob Hill, and the cling-clanging noises they make echo through my open window as I write, reminding me that I live in an era of unprecedented mass movement in human history.

Each morning, with my window open to the street, I hear Chinese, French, Spanish and a few unidentifiable languages spoken. These days, even if you don't travel, the world literally comes calling at your doorstep.

The increase in tourism flows naturally from the fading of geopolitical problems associated with the Cold War. Old enemies shake hands and trade moves swiftly back and forth across now-porous international borders. And while the cynic will tell you that tourism has done some damage to the environment and turned the natives of poor countries into beggars and prostitutes, it does have its inspiring aspects.

Costa Rica's spectacular rainforest has not been cleared for cattle grazing (as in neighbouring countries) largely because tourism is seen as more important than cattle. And many ruins -Angkor Wat in Cambodia or the Valley of the Temples in Myanmar -are being restored. Traditional dances -in Bali, Phnom Penh and Bangkok -are kept up or restored in hope of getting the tourist dollar.

Besides, a Japanese tourist crying at Elvis' shrine, Graceland, in Memphis is no less poignant than an American pacifist weeping at the place where Gandhi was assassinated in India.

We have come to mean something to each other in the global village. As nation states become less powerful and identities are multi-layered and cosmopolitan, the global village becomes more of a reality.

But why travel? Why trudge abroad when we can be, as Paul Russel puts it, "stationary tourists" logging onto the Internet and surfing the world in the comfort of our bedroom? The cynics would contend that the going is not worth the fare anymore, that paradise was lost long ago.

We travel out of necessity, of course. To trade, to conquer, to proselytise, to discover new homes. But, most importantly, we travel to find ourselves.

The world may have been discovered long ago, but not one's place in it. One watches gorillas play in their habitat or one descends into dank and dark tunnels of other ruins to imagine one's own life lived otherwise, elsewhere.

But some of us travel for a deeper reason, the deepest perhaps. Ultimately, a traveller is a pilgrim on a quest. The outer space explored is the metaphor for the inner life expressed. Every trip thus becomes a story, and every new passport with its pristine pages is, essentially, a novel waiting to be written. The traveller emerges a bit wiser from the experience, with a story or two to tell if and when he or she comes home.

A few years back, a homeless man in his 40s with a little monkey moved into the front step of an out-of-business shop near my office and we became friends. I always caught him with a thick book, and, unlike many other dispossessed, he displayed a remarkably sunny personality.

One day I asked him, "How long have you been homeless?"

He laughed and said: "What made you think I'm homeless? No, I'm a traveller."

Andrew Lam in Petra, Jordan, circa 2003.

When I returned from a trip to Southeast Asia a few months later, the man and his little monkey were gone. Those who knew him told me that he had decided to go to Mexico to check out some new sites and did not know when or if he would be back.

Though I shall miss him, his friendly smile, his sunny disposition and his funny pet in a vest, I'm glad that he picked up and went.

The man and his monkey reminded me strangely of a childhood hero, a monk in the famous Chinese 16th-century epic, Journey To The West.

On a quest to find the sacred Buddhist text, he had to journey through a thousand exotic landscapes with his band of misfits, with the Monkey King as his guide.

Home for them became anywhere and everywhere, its logistics translated into a beatific vision of freedom. They turned the cold hard ground into a soft bed and tugged the night sky into a blanket filled with stars.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and author of the "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," and "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." His latest book is "Birds of Paradise Lost," a short story collection, was published in 2013 and won a Pen/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 2014.