Like her 2009 novel Entertaining Disasters, Nancy Spiller's new book concerns itself with conventions in cookery and American cuisine. Compromise Cake is, however, is the much more personal book, a memoir telling the story of the hard-won bonds of love and sympathy the author forged by working with the recipes her mother wrote out by hand on three-by-five cards and kept in her wooden box.

Marguerite Soult Spiller died in 2007, so this volume, whose subtitle is Lessons Learned From My Mother's Recipe Box, becomes a daughter's moving tribute to a woman's life forestalled by social isolation, personal disappointment and mental illness.

I recently had a chance to sit down with the L.A.-based writer and visual artist when she was in the Bay Area doing readings for her new book. Because Nancy and I have a long friendship, our conversation ranged easily over the plight of those in our mothers' pre-feminist generation women of the 1950s and early '60s. These were women who'd gone to college and had once imagined themselves on the precipice of an exciting future, only to be sent out of the workforce resigned to fulfilling themselves as stay-at-home moms.

Nancy's mother was caught in a demographic downdraft in which cultural expectations for women seemed at once sentimental and demeaning. The happy housewife effortlessly running her perfect household was a role performed with ease only by actors on sitcoms yet our real mothers were judged by this, only the latest of the more pernicious fictions that would soon have Santa bringing these women's daughters their Barbie dolls.

These were women who relocated because of their husbands' jobs to live far from their mothers, sisters and intimate friends, a life of relative leisure and privilege that was also fundamentally isolating. So alone were these women they'd rarely catch a glimmer of how very common their own sad story had become.

Nancy and I talked about the political nature of cooking and eating and how in buying those foods we choose to spend our money on we accept or reject cultural values. We spoke too about the nature of householding and childrearing, labor denigrated as "women's work" in the post-war America of our childhoods.

This was the era, as Nancy tells it, in which Betty Crocker rose in prominence in the public mind, becoming second only to Eleanor Roosevelt in popularity though Betty Crocker was corporate creation and resembled no living person.

Nancy spoke of the need for women to give themselves permission to not only make art but to actually tell art's more fundamental truths, the deeper, sadder, more realistic stories often denied to women and children.

She continues to get her own inspiration for her work from those women who defied both the expectations and the odds, those like the writer Doris Lessing and the painter Alice Neel, whose quotes she's used as this book's epigraphs. Each lived into late old age, Lessing enjoying a long career, while Neel worked largely without recognition as she raised her children in what was often brutalizing poverty.

In the case of Nancy's mom, Marguerite Spiller left teaching after only a single year, then found herself stuck in a house in a Northern California suburb on a cul-de-sac with four kids and no car. Compromise Cake is an eloquent testament to her homemaking skills as this was the only form of art-making available to her. Cooking became a way of feeling connected to her own past as well as a mode of self preservation.

"Her artistic acts were often hidden and subversive," the author notes, finding expression in the recipes her mother wryly named "My Man Cookies" and "Dark Cake." Marguerite is portrayed as mordantly funny woman, her humor growing necessarily more grim as isolation took hold, beginning in earnest when their father left.

After her divorce, Marguerite took to brightly singing while working around the house to the tune telling that how love and marriage went together like a horse and carriage, this during the dawn of the post-industrial age in which old-fashioned buggies were long gone.

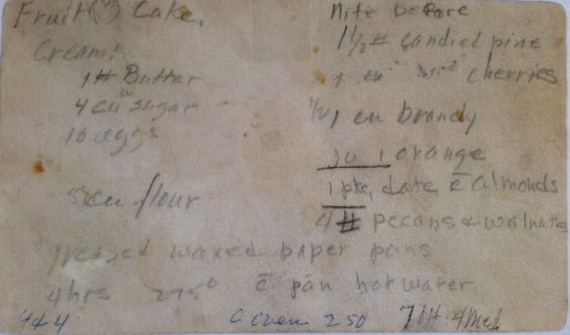

Here Nancy Spiller has done the radical thing: instead of glossing all this in the rosy light of vague and nostalgic memories, she's taken a hard look at what made her mother's story both typical and unique. "My mother was the master of the unspoken metaphor," Nancy told me, saying she found her mother's teaching certificate folded up and filed the recipe box.

The book's chapters are organized around one or two of the handwritten recipes from the box, with an examination of where each may have derived. The author offers comment on the evolution of American culinary taste by tracing the advent of such popular ingredients such as Crisco.

Because the holidays are upon us Nancy has been making the fruitcakes she's given every year as Christmas gifts since she began baking them in college. She includes both mother's and grandmother's recipes in the book, as well as the one she's developed herself, a rich dense cake darkened with molasses.

Fruitcake comes weighted with historic tradition, requiring such time-consuming techniques and costly ingredients that it easily takes on personal and symbolic meaning. Nancy's own fruitcake was recently featured on the Hallmark Channel's morning show and can be viewed by clicking on this link: https://cision1.box.com/s/18azzykwcxgni52sp2k9

For the past several years my cousin Carolyn Roll has flown to the Bay Area from Salt Lake for a fruitcake-making weekend, in which we gather about us as many willing daughters and nieces and female cousins as we can persuade to come.

We make fruitcakes for our husbands, brothers and sons using her mother's recipes, as an act of remembrance of Janet Vandenburgh Godfrey, my aunt, who died in 2010, a woman who left medical school to raise an entire passel of unruly kids including those born to my own parents. This fruitcake-making and sharing provides each of us with a way to remember her through her recipe.

Sadly my cousin and I weren't able to get together this year so I'm giving Compromise Cake instead. Nancy Spiller's gouaches have a lovely light touch that puts me in mind of the work of Maura Kalman. You can buy the book on-line or with a phone call and have it gift-wrapped and shipped from your favorite independent bookseller.