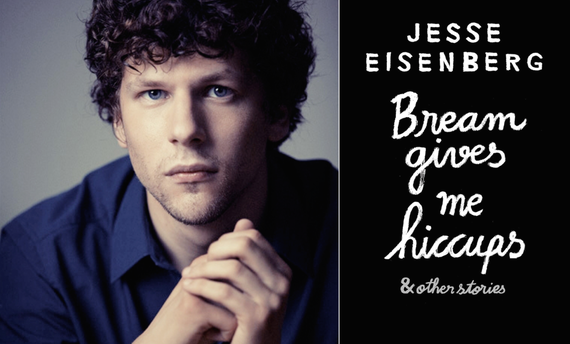

Most first associate the name Jesse Eisenberg to his awkward, perpetually teenage mumblings on the silver screen. He makes his living off acting -- artfully so in films like The Social Network and To Rome with Love. He's charmingly staved off massacres in Zombieland and correctly identified Lou Reed song titles to impress Kristin Stewart (why else?) in Adventureland. He can even soon be seen freshly shorn, while portraying Lex Luthor in Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice. Yet Eisenberg has also shown impressive prowess when laying down words to paper (or pixels). Besides penning and staging three well-received theatrical productions, he's published short stories and other works with The New Yorker and McSweeney's. Many of the humorous stories originally published in the latter now see a broader audience by inclusion in Eisenberg's debut collection, Bream Gives Me Hiccups, released this month via Grove Atlantic. Eisenberg recently took a break from filming a new Woody Allen flick to speak with the Barnes & Noble Review by phone about opening day anxieties, drunk carrier pigeon messages, New York neuroticism, Candy Crush, and skipping the comment section. The following interview is an edited transcript of that conversation. -- Beca Grimm

The Barnes & Noble Review: How do you feel about the book coming out?

Jesse Eisenberg: I guess I feel nervous. My regular job is so public: usually when a movie's released there's just a barrage of horrible things going on. I feel nervous and I really love it. I'm so flattered that a publishing company would put it out. I'm honored that people who've read it have liked it. But mostly nervous for the inevitable barrage of criticisms.

BNR: How do you feel a book coming out is different from a movie coming out? How do you prepare yourself for hearing reviews about it?

JE: I try to stay away from reviews. They can be really distracting and not very helpful. It's my limited experience -- with this book -- people who are reading a book spend an intimate experience with a book for two hours, reading on their own. It requires a lot of participation on the part of the reader. Their response is going to be a little more sensitive and nuanced than a typical moviegoer's response. You see movies in a group. Usually there isn't a required participation with the audience. You end up getting -- from a casual moviegoer -- a chronic knee-jerk reaction that a book doesn't really inspire.

BNR: Do you also think this book is more personal than appearing in a movie, because this is coming from your brain?

JE: Yes. On the other hand, when you're in a movie, you're emoting and your face is in it. So in a way, a movie is very personal as well, because strangers are watching your face. It's like the worst experience from high school. On an international level. People making fun of your clothes and your dumb face, your stupid haircut in a newspaper. Whereas with a book, people are reading my thoughts and ideas. My stupid haircut is nowhere to be seen.

BNR: I think your haircut is not stupid. For what it's worth.

JE: Well, thanks a lot. You're clearly a thoughtful, sweet person who does not write on the Internet.

BNR: I do write on the Internet. I just try to be nice about it. You've been writing for a long time. I read that you're been working on short stories since your early teens. How did you get mixed up with Dave Eggers and his whole McSweeney's crew?

JE: I can't remember how I discovered McSweeney's. Once I did, I realized people could write short humor with not just standup comedy. That there was this gray area between humor and character. My mind illuminated. I started writing for McSweeney's and got rejected for a few years. At one point I started getting accepted. Then I started writing for The New Yorker -- again, got rejected for a few years, then finally accepted. I'm so happy I was rejected, because it forced me to really hone my skill sets. I'm in a very weird position as an actor where people will read my work -- not necessarily like it, but will plan to read it just because of my position as an actor. The best thing about rejection is some injection of reality. That came from both of these experiences.

BNR: By being rejected?

JE: Yeah, exactly. Because if you're a motivated person, rejection is very inspiring. If you're unmotivated, rejection serves the opposite purpose. You would stop working.

BNR: You said that because people are going to recognize your name, there's a better chance you'll get eyes on it. That's obviously true. How do you deal with that pressure of knowing people are going to read your work because of that name recognition alone?

JE: There's two sides to that. My third play in New York was just produced. The company who produced my play -- they're very well respected. They don't want to risk their reputation on an actor's play that's not good. In a way, my plays have to be better. The advantage for me is that my work is probably seen more quickly than other writers, but I think the quality of it has to be the thing. I know people will read my stuff. But right now I have to do a little more preemptive self-censorship.

BNR: That's probably a good thing, though. Don't you think?

JE: It's good, it's good. Given both life options, I'm happy to be living the one that I'm living. I do, in a way, kind of miss the freedom of being able to do the most crazy thing and throwing it out into the world.

BNR: With less accountability.

JE: Exactly.

BNR: How do you use different parts of your brain for writing comedic short stories versus plays?

JE: I was reading this really interesting article that John Steinbeck wrote, and he talked about -- and it's wrong -- but he talked about how Of Mice and Men was a failure. He said he tried to write a play but because readers have a difficult time reading plays, he tried to put elements of a novel into the book. Character descriptions, setting descriptions, writing "he said" instead of just the character's name and a colon like you would have in a play script. But otherwise he said it's the same thing. That's how I feel, too. It's the same thing. I write a lot of first-person, and that's the same as a character in a play doing a monologue. There's a real overlap. As an actor there's another element, which is embodying the emotional experience of a visual person. That's what I've been training to do since I started acting. That informs writing as well, because you're trying to understand the emotion underneath a character of fictional situations. That's a difficult and wonderful experience to have as an actor.

BNR: I thought your ability to hone the teen voice in several different essays was really awesome. Especially the frustrated narrator Harper in "My Roommate Stole My Ramen: Letters from a Frustrated Freshman," because you were probably never a teen girl. How do you nail that? Even just the perspective in "An Email Exchange with My First Girlfriend . . . " Maybe there were some relatable elements there, like the boy's parenthetical self-conscious aside, "(he said sarcastically)"?

JE: The truth is I have a younger sister: she calls me in her first year of college and complains about something minor with a kind of anger I've never seen from her. That happens to young people when they are experiencing some new physical transition. I told my sister how absurd she sounded and we both laughed about it. I thought of this character who is this eighteen-year-old girl who is full of rage. A rage that's never been expressed before. I thought it would be really funny to have her have rage against otherwise silly complaints, silly inconveniences. Like her roommate taking one of her soups. Because of my acting background and my sensibilities, I created this character who's not only angry but deeply lonely and desperate for some human connection. That anger actually manifests from this desperate longing to be loved. She has this roommate she hates, but she's desperate to be touched by her. She has a teacher who she thinks is attractive, but she accuses him of sexual harassment. She doesn't know how to direct her need for attention. Her way to ask for attention comes out as rage.

BNR: It's almost as if she rejects any affection she gets. When the roommate she calls The Slutnick chases her out of the concert and tries to hug her, she's receptive and thankful for it but ultimately rejects it to continue this invented battle in her head. The teacher gives her a very off-the-cuff compliment, then she goes off to try to report him for harassment.

JE: She talks about her parents, who never give each other any affection. So she doesn't know how to accept it. She doesn't see the gray area. She sees the teacher giving her compliments as sexual harassment. She doesn't know what affection is. She doesn't know how to take that in the way it's actually intended. Her roommate has a well-adjusted family, and she doesn't know how to accept that because she has never experienced it. She has the parents who are cold and aloof. She doesn't know how to accept real affection.

BNR: Right. The way you're speaking of Harper's parents -- who she describes as barely speaking to each other and never doing anything fun -- is definitely a theme: a resounding dissatisfaction among parents. Parents maybe regretting their children, definitely regretting their marriages. The mother in "My Mother Explains Ballet to Me" saying, "Your father's the only man I've ever been with. Can you believe that?" The father in "My Prescription Information Pamphlets as Written by My Father" describing the prescriptions like "Twenty-six years married to the same woman and three Carnival Cruises together!" What brought that about?

JE: I see this trend that is funny and also very saddening of parents speaking to their children in a way that ultimately traumatizes them. But the parents don't realize it. I'm writing about the product of narcissism. The children of narcissists turn into these damaged, introspective people. Harper's the child of clearly narcissists. The boy who goes to the ballet with his mother is with a narcissist. Narcissism is fun to write about and I've written about it a lot. It's also neat to write about what that produces. As we were talking about, they don't know how to accept affection and love. That parent has a monopoly on their child's form.

BNR: Absolutely. The neglectful mother in "Bream Gives Me Hiccups: Restaurant Reviews from a Privileged Nine-Year-Old" speaks to her son in weird jokes he doesn't get but adult readers understand. It's a premature maturation of that relationship and how that impacts the child.

JE: Yeah, that's another avenue of how self-involved parents could have that effect on a child. In some cases the children will become their own parents, looking for advice from within instead of from the parent. I'm friends with a psychologist who deals with adolescents and tells me a lot of kids end up self-parenting. So they kids will mature prematurely -- but oftentimes will have very healthy inner lives -- because they had to self-parent and fend for themselves.

BNR: I find it interesting how you chose to show how both sides of that introspection can pan out. The nine-year-old in "Restaurant Reviews" seems like he's using it in a very positive way, gaining all this wisdom like, "I guess I feel bad for people more quickly than Mom does and that is one difference I've noticed about us," and "Sometimes the things that are scariest are the ones you don't understand." Then you see Harper who is just terrified and self-sabotaging.

JE: That's exactly right. There's two sides to the thing. They probably have the same kind of parents, and yet one child is being able to direct it toward premature self-actualization, while the other girl seems possibly permanently stunted.

BNR: When did you start to get interested in these relationships?

JE: It's dramatic because there's something inherently sad about parents and children not connecting with each other. I live in New York City, so I'm surrounded by these types of people -- not that they don't exist elsewhere, but they certainly do exist in New York -- this neurotic narcissism. I can't actually say I know people as extreme as this. I've seen people on the train like this -- briefly. But I can't say I'm actually friends with people like this.

BNR: There's this tangible fear of getting stuck in situations like this -- in parenthood and marriages. These parents are clearly miserable. Do you ever think about that personally?

JE: Yes, I think very much about it as I get older -- what kind of parent I'd want to be. And I think all the time about how you don't realize that the little habits you acquired will affect a child in a way that I'd never be able to foresee. So yeah -- I think about that all the time. And of course it's easy for me to criticize other parents when I don't have a child of my own. I could be the worst parent with the best intentions.

BNR: That's what I think is one of the scariest parts. I can't imagine parents set out to be shrugging the whole time.

JE: Exactly.

BNR: To shift gears, how did you decide to write about Alexander Graham Bell's first five phone calls? The fourth one, specifically, is a drunk dial.

JE: I'm very interested in history, and I read that Alexander Graham Bell made this telephone call to his assistant Watson and said, "Watson, come here. I want to see you." Actually, I think I heard this joke when I was ten years old on Comedy Central. It was a comedian saying his cellphone ringtone was Beethoven. He said, "I don't think when Beethoven was writing Symphony No. 5 he thought in 100 years someone would hear it and say, 'Oh shit. It's my mom.' " I thought that's so funny -- the way modern technology has appropriated otherwise nice things for dumb modern pleasures. The way we've appropriated the activity. Like getting drunk and calling a friend. At one point the telephone was a revered wonder. I thought it'd be funny to explore the natural evolution of telephones, but within five phone calls as if to say it starts out an incredible curiosity and winds up three days later as a boring way to communicate what you're doing with your buddy.

BNR: It was a very quick evolution.

JE: We get used to something so quickly and then use it for something stupid. That's what happens now. Technology is being created so rapidly and the next thing you use it for is the dumb thing you used the previous incarnation for.

BNR: Like sending drunk carrier pigeons?

JE: Exactly!

BNR: What do you think Alexander Graham Bell would think of Candy Crush and Tinder?

JE: I don't know if he's a follower of McLuhan's "the medium is the message" but if he were, he'd probably be really upset. When I have a play in New York and I hear it's performed elsewhere, my first feeling is so excited and flattered it's being performed in a college or a different country. My next feeling is, "Oh my god. They're probably missing the point of this part." I might be wrong, but you feel protective of your creation when it's out in the world.

BNR: How do you stop yourself from obsessing over something like that?

JE: I have to keep in mind that I've done plays in New York and I get the best actors in the world. My last play had Vanessa Redgrave as the main character. I think I'm the luckiest playwright to have these wonderful actors in my plays, but you end up thinking that line wasn't said correctly. The way I get over it is by thinking my intention isn't necessarily the best way to do it. Once you put your own taste in perspective and realize that it's just your own, the goal is to not only collaborate but also appreciate someone else's wonderful work.

BNR: Would you say you have a natural predisposition to want to be in control with things you create?

JE: Yes, I do. I love working with movies, but I don't watch them for that reason. I love being in control of my acting performance. Often it makes me nervous to think it's being edited and manipulated by other people, so I don't watch the movies. That kind of burden of control is immediately lifted. When you act in a movie, the thing that you're doing on set is very far removed from the thing that's on screen. It's edited, it's underscored, it's an angle that emphasizes one part of your face. The way to ease the burden to just not to watch the thing. When writing books, you have to read things over and over again. What you don't have to do is read other people's critiques of it. Often times it's not very comfortable. People are writing critiques based on their very personal need for expression. It's not very helpful.

BNR: Right. It's based off their own lens and experiences and interpretations.

JE: Or a need to write something mean for whatever reason. Or by contrast, a need to write something nice, which is also dangerous.

BNR: Why do you think that can be dangerous?

JE: As soon as you assign value to people telling you how to do your job, then you are doing your job for some other reason. No one knows my book better than I do, and no one knows the reason I have written it better than I do, so I don't understand how it would be helpful to read somebody else's impression of it. Now if no one reads the book, and my publisher refuses to publish the next book, then I might have to start self-assessing. But until that happens, the best way to do one's job is for themselves, especially in the creative field.

BNR: Right. But don't you feel like there could also be some value in constructive criticism, and in considering intent versus impact?

JE: Absolutely. I think that's great and why it's nice to surround yourself with smart people who will be honest. In my experience, the Internet is not filled with those people. So the temptation to do a Google search on something you've worked on will not yield happiness or helpful results. If you surround yourself with people are thoughtful and nice and honest, I think you'll have much better odds.

BNR: Sounds like you take the same approach many journalists do with skipping reading the comments.

JE: I really like David Brooks, who writes for the New York Times about books. He's a conservative, as well, but he writes about sociology -- which I am interested in, it's what I studied in college. I read something the other day of his about gratitude and saw over 100 comments. And they were vicious. I would not have been able to find a way to criticize this, and yet 990 people did.

BNR: I saw Guided by Voices in high school and at one point Robert Pollard grabbed the mic and said, "Have you realized that no matter what anybody's shouting at a show, they're all saying the same thing: 'I exist'?" Commenting on the Internet can be similar.

JE: Very interesting. Yes. "I exist." That's a very good way to put it. Also, very sad.

BNR: How do your studies in sociology contribute to your writing? How does that afford you a different angle in writing all these first-person narratives?

JE: I studied sociology and anthropology in school. There's been no acting class that's been as helpful, no writing class that's been as helpful as learning sociology and anthropology. What anthropology teaches you is that there is equal value to different cultural perspectives. And that is the best thing you can learn as an actor. If you're playing, for example, a villain in a movie, the most important thing is to know there's equal value to that person's perspective as there is to the hero's perspective. And once you do that as an actor, you start to defend your character's decisions -- even though he's the villain. And as a writer, for example in this book, if I write about the sociological trends of divorce in the modern era and how that impacts young people -- that first story is about the product of divorce, trying to navigate his relationship with his mother. And the other stories that take place in other countries, you see the funny American perspective. They're related to my studies in anthropology the way in which an isolated America -- a gross generalization -- but a country that's wealthy and geographically removed from a lot of other places can think the more isolated you are, the more removed you are from looking at other cultures, countries, races, ethnicities. That all informs the stuff I'm interested in, the stuff I write about -- more than the short story classes I've taken.

BNR: How do you plan to spend the release day of Bream?

JE: [Laughs] Filming a movie, so I'll be on set. Luckily it's not like a movie, waiting for the box office response. That's the most nerve-racking experience, sitting around waiting to see if teenagers are into it. With books it's a more gradual rollout. So I've been through the wringer already. I don't really feel that nervous. I'm still comforted by the publisher, who agreed to publish it so beautifully. It's been really the nicest experience. I just wish movies had one percent of the kind of attention and calmness that the book world has.

BNR: Do you think you'll put out another book one day?

JE: Oh yeah. This has been so wonderful. I can't wait to do it again.