Christmas Eve marks the anniversary of one of the darkest moments in U.S. labor history: On that day in 1913, more than six dozen people died in a stampede following a false cry of "Fire!" at the Italian Hall in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The tragedy occurred during a miner's strike in the "Copper Country," in a time when unions were not protected by law and strikers were more likely to be beaten and fired than to be invited to a bargaining table.

It began in the summer, when the Western Federation of Miners reached a membership level that allowed them to call an effective strike. Most of the copper mines were situated in a line on the north side of the peninsula and the strike worked: The mines shut down completely. The mines called for the National Guard to be sent and also hired hundreds of strike breakers -- an archaic profession for men who wanted to bust heads legally. Soon the area was swarming with National Guardsmen, out-of-town strikebreaking thugs and striking miners.

Michigan's governor, Woodbridge Ferris, recalled the bulk of the National Guard when it became apparent they weren't needed. For the most part, the strikers had not been violent and the Guards had little to do. The day after the Guard was recalled, strikebreakers shot and killed two striking miners in broad daylight in a little corner of the copper district called Seeberville. It was just a hint of things to come.

The sides dug in deeper. The WFM sent out calls for help and labor leaders like Mother Jones and Clarence Darrow lent moral support. The mines were flush with cash though, and bet they could starve the workers into ending their strike. Then came winter.

Michigan's Copper Country winters are famously harsh. Snow is measured in feet and temperatures routinely drop below zero. While many of the strikers were recent immigrants from Finland, the prolonged strike inspired many of them to leave before waiting to see whether the strike would end before the snow would melt.

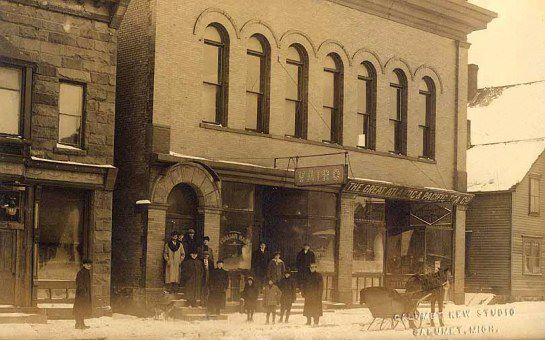

The heartiest strikers who stayed decided to have a party on Christmas Eve, particularly for their children. More than 500 people attended the event at the Italian Hall, in a town now known as Calumet. It was called Red Jacket at the time and was the home of the Calumet & Hecla mine, the biggest of them all. Songs were sung and presents were given to children. Adults chatted and a light dusting of snow began to fall as dusk turned to night. For a moment, the strike was forgotten.

Then, a stranger stepped into the main hall and yelled "Fire!" There was no fire but panic spread through the building. Most people rushed out the only way they knew: toward the steep staircase that led to the street. Someone tripped and fell and soon a pile of bodies blocked the stairwell. When the volunteer firemen arrived just a few minutes later they could not untangle the mass from the street level. They had to climb the fire escape and perform the rescue from the top. At least 73 in the pile were dead, of whom perhaps 60 were children. Witnesses would later say they could identify the man who had raised the false alarm and much of the evidence pointed to his occupation: He was a strikebreaker.

The president of the WFM, Charles Moyer, sent telegrams to the outside world demanding an investigation. For his effort, the local sheriff stood by as pro-management thugs beat and shot him. They dragged him to the train station and put him on a train with a dire warning: They would kill him if he returned. The local English-language newspapers spun the story to say Moyer had left town suddenly after trying to "capitalize" on the deaths at the Italian Hall. One paper suggested he had merely skipped town to avoid paying his hotel bill.

The funerals for the dead were a spectacle. Services were held in several churches at the same time and the mourners filed into the streets and walked in a long procession to the cemetery outside of town. White coffins for the children were carried by men while the adult coffins rode on horse-drawn carriages.

The local coroner convened an inquest and took testimony over three days so he could publish a report exonerating the most likely suspects: Mine management and its strike breakers. Anyone reading the transcript of the hearings today is struck by how unfair they were. Witnesses who spoke other languages were asked questions in English and required to answer in English. Many witnesses were called who were not at the Hall or who had not seen what happened.

In the end, the official verdict was that no one knew what happened at the Hall. But the problem for the local powers of 1913 is that we do know, and we can remember: The man who cried "Fire!" at the Italian Hall was a strikebreaking thug. He might not have intended to kill anyone but he certainly set out to disrupt the party. His lack of foresight regarding his action does not exonerate him or his masters.

One lasting legacy of this event is the famous quote from Schenck v US, where Oliver Wendell Holmes famously wrote: "The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic." He wrote those words in 1919, and while he did not refer to the Italian Hall disaster he most certainly knew about it. It had been front page news at the New York Times and most other major newspapers of the day just six years earlier.

Italian Hall needs to be remembered for more, though. It was centered in a labor dispute, at a time when workers who stood up for their rights could be fired, beaten or worse. At least 73 people died at the Italian Hall in 1913 during a struggle for workers' rights. They must be remembered this, and every, Christmas Eve.

Steve Lehto is the author of Death’s Door: The Truth Behind the Italian Hall Disaster and the Strike of 1913.