The Itsy-Bitsy Book Club started a couple of years ago, when a friend and I picked out a book together. It's a great way to connect with a friend or two and read something interesting. Even better, it doesn't involve the demands of a regular book club -- no monthly meetings, no reaching consensus with a large group.

Here's how to set up your own version:

1) Choose a friend. Ideally, the friend is someone you don't see often, perhaps someone who lives far away, but a person with whom you want to stay in touch. My Itsy-Bitsy Book Club partner is a college friend that I usually see only once a year at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference. This year, another college friend at the conference jumped into our club.

2) Choose a book. The book must be one neither of you have read, preferably one that's not even on your lists of things to read. If you need a recommendation, browse your nearest physical bookstore, perhaps simultaneously so that you can text or talk on your cell phones as you decide together. Luckily, my friend and I browse the conference book fair and choose something from a small publisher. My friend Rachel Hall chooses the book, but I retain veto power.

3) Exchange phone calls or email messages as you read. You may want to set a reading schedule, or you may find that an email message saying that you've started reading nudges your friend. Sometimes, one of us reads the book on a long flight home from the conference, but it took weeks for all three of us to finish this year, in part because I started after one of us finished.

We've not chosen books from best-seller lists. Such books may be quirky, sometimes challenging, often beautifully printed. Last year, we read Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns; it was published by Dorothy, a project dedicated to publishing books by women. In 2011, we read In the House by Lynn Kilpatrick; it was published by the University of Alabama Press, under their FC2 imprint.

This year, we returned to the University of Alabama Press and FC2 for Correction of Drift by Pamela Ryder. The book is a fictional account of the kidnapping of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh's first-born son. I'm interested in aviation, so I gave the nod to Rachel's selection. I was just slightly surprised that only in the title story is aviation -- and Charles Lindbergh's famous flight -- woven into the elegantly unfolding language.

The subtitle claims this book is "A Novel in Stories." A quick perusal of the blurbs on the back cover point to the un-novel-ness of this collection. Gordon Lish, to whom the book is dedicated, claims that Ryder has "made that which no one else has made." Fiction writer Pat Conroy asserts that the author "brings something new to American letters."

Rachel, Mary Cantrell, and I agree that Correction of Drift is not a novel. Moreover, the stories don't work as chapters, and most don't even work as stories per se. That the book is labeled a novel on the cover will lead some readers to toss the book quickly into the recycling bin. The mislabeling, however, made me think about what I expect from a novel. I expect time to move linearly, even as there might be flashbacks in a novel. I expect a point-of-view character or a stable narrator, a voice or a perspective that carries me through the novel. I expect a structure that connects the novel's parts. I appreciate experimental writing, but the term novel sets up particular expectations, perhaps requires a critical mass of novel convention even as some of fiction's conventions are challenged.

While the subject matter -- the Lindbergh kidnapping -- connects the individual parts of Correction of Drift, the reader is set adrift in relation to timeframes, narrators, and many other aspects of fiction upon which we usually rely. That said, this book taught me how to read adrift. The most obvious technique Ryder uses to reorient the reader to this different style is excerpts from newspapers and other documents in between the sections.

In addition, readers must begin adjusting their expectations on the first page of "In the Hands of the Pigman," which begins with the word "they" even though the story doesn't ever name these characters. Instead, their shoes are described, and italicized memories interrupt the fictional present (which is the historical past of the night of the kidnapping). Within a couple of pages, the ladder is revealed, and it becomes clear that the three characters are the kidnappers on the night of the kidnapping.

My friend Rachel thinks of Correction of Drift as a prose poem. The section "Boy Is Gute, Etc." even looks like a poem. "Dreams, Sightings, Expressions of Sympathy" uses mostly short paragraphs and intersperses letters Mrs. Lindbergh receives. Some letters share dreams that strangers have had of the missing boy: the kidnappers are feeding him well, or the boy is in a plane over water. Other letters offer advice: pay the ransom, or search the river. The fractured narrative mimics the state of mind of a mother whose child has been plucked from his crib and out the bedroom window.

My two favorite sections use similar techniques. "In the Sitting Room" focuses on Violet, the Lindbergh's maid. The kidnapping has thrown the household upside-down, and Violet is, of course, caught up in the tragedy and drama and the jumble of her life. This piece reveals that Violet has seen tragedy before, and she's worse for wear.

The final section is a six-page paragraph. The title "Graveweed" refers to a thorny plant but also the tragic event. Within the first few lines, "A migrating bunting" suggests a bird, decorations used to celebrate Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight, and the clothing of the missing toddler. The landscape of the Lindbergh estate is described simultaneously as it is during a present-day tour and as it was on that fateful night in 1932. The form embodies a collapse of timelines, a collapse of human history and the natural world.

If you choose to read Correction of Drift, don't read it as a novel. Read for details and language. If you choose a different book for your Itsy-Bitsy Book Club, I urge you to challenge yourself and your reading habits. But even if you pick a bestseller for your Itsy-Bitsy Book Club, you will find a new connection with a friend.

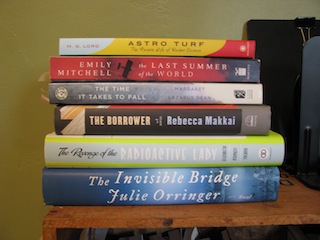

Photo, by Anna Leahy: That's The Isty-Bitsy Book Club: one friend, one book, once a year.