Photo credit: Beatriz Schiller.

It is one of the most pressing questions of American dance: how should we preserve the work of great 20th-century choreographers who glued their style to a generation distinct and removed from our own?

Merce Cunningham answered the query simply when his troupe disbanded several years after his death, his oeuvre relegated to other groups that perform a diverse body of repertoire. On the other hand, Martha Graham Dance Company modernized, gathering a new slew of technically precise, emotionally vibrant dancers who could execute Embattled Garden and a Nacho Duato commission on the same program. In 2011, Claudia La Rocco mentioned the deterioration of Trisha Brown's ensemble in The Brooklyn Rail. In contrast, Paul Taylor and Twyla Tharp still kick with vitality -- both are being presented in American Ballet Theatre's 75th-anniversary fall season -- and perhaps they're the last of the artistic vanguard from a golden age of movement creation in the U.S.

And then there's Mexican American choreographer José Limón, who hasn't been around for over four decades. He posits an interesting dilemma: even in his heyday, critics wondered where he fit among the modernist and post-modernist schema. Born in Culiacán, Limón moved to Los Angeles with his family as a child; could his repertory represent Mexican culture? Unlike most dancers, he started training twenty years into his life after a stint at UCLA as an art major; what does it mean for a choreographer to study visual art first, then dance? A controversial, idiosyncratic character, Limón could not be divorced from such quandaries. He still can't today, but atop these more profound, individualistic comments lies the ever-present problem of relevance.

Photo credit: Beatriz Schiller.

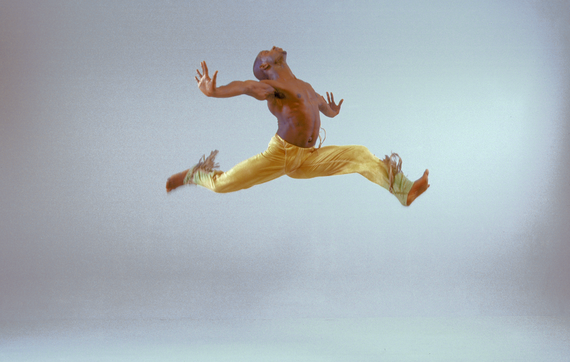

No, Limón does not feel relevant to the 21st century, as his company celebrates its 70th anniversary season. It's sad but true, evinced by the José Limón International Dance Festival at the Joyce, which has monopolized the theater for two weeks this October. Last Saturday, when I attended, The Unsung opened the bill. Limón's silent antler piece still has some of its immediacy; 11 men stomp in unison, swarming one another in an almost militaristic, robotic heap, but when they break off for solos, they are tremendously emotional and urgent. They extend into an attitude back, legs bent at a right angle and parallel to the ground, until their bodies collapse and emerge outward again like a flower at dawn and dusk. They migrate forward, their legs flying in battements à la seconde, their eyes dauntingly focused all the while. Guest artists from the Royal Danish Ballet juxtapose the dancers from Limón's company, both techniques clashing in line and aesthetic. Still, the three visitors -- Charles Andersen, Gregory Dean, and Gábor Baunoch -- are lovely to watch alone, their muscles taut as they articulate types of motion unaccustomed to their physicality. The Unsung is one of those works that you set your retina on while your mind drifts to another world, and everything feels dream-like and mysterious. In other words, it's background noise to whatever's occupying your headspace. In this way, it's not altogether obsolete, and makes a persuasive argument for the novelty of Limón's genre. Now, it feels a little like an extension of identity politics -- perhaps too brooding for its own good -- but it holds up.

Unlike the last two offerings, which linger and bore. The Moor's Pavane, one of Limón's most recognized dances, presents an abstract narrative based on Shakespeare's Othello. Durell Comedy, potent in The Unsung, is less convincing as a homoerotic Iago, or the Moor's "friend." As he wraps his legs around Francisco Ruvalcaba (the Moor), whispering in his ear, his alignment is unnatural, disrupted. And so it is with all of the courtly quartet in The Moor's Pavane: as they cross in patterns and steps that mimic 16th-century aristocratic dancing, they look just like Limón's soloists in black and white videos from decades ago. Call it extraordinary preservation if you like, but to me, it felt tired, like a relic, the bare bones of something that once made dance enthusiasts rise to their feet in awe.

Photo credit: Barratt.

Finally came The Winged, where human insects scurry around, collecting near each other and nestling together for camaraderie. It chugged on much too long. The most exciting sections came at the end -- Brenna Monroe-Cook isolating her torso with ease as the Sphinx, Kurt Douglas pounding each position as Pegasus -- but by then, this viewer was much too lulled to care. Of course, a standing ovation marked the curtain's closing. And yet one look at the audience, and you must wonder if they're more nostalgic than enthralled: most of them probably saw Limón's work when it debuted, and it's always nice to reminisce.

Still, for a 20-year-old who's more invested in the present and future, the fresh fall air proved a necessary change after over two hours of living in the past.

The José Limón International Dance Festival runs at the Joyce through October 25.