By Joy Leisen, Special Projects Coordinator, Huron Pines

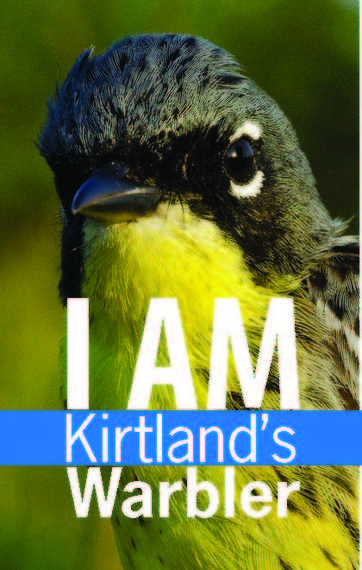

Mystery, intrigue, tragedy, controversy, and even murder--the story of the Kirtland's warbler, North America's rarest songbird, has it all. The depth of this tiny bird's relationship with Northeast Michigan's communities is as unbelievable as the physical feats it accomplishes. These half-ounce flying featherballs, the embodiments of pure determination and unbridled enthusiasm, fly 3,000 miles each year to the Bahamas and back to nest in Michigan's unique jack pine forests. Once at the brink of extinction, the Kirtland's warbler population has recovered to 4,000 birds thanks to the tireless efforts of dedicated people. But there are new challenges on the horizon for the Kirtland's warbler, as it will soon come off of the Endangered Species List. This change will mean that the Kirtland's warbler will lose funding and legislative protection. To continue the habitat management necessary to sustain the population of this amazing bird, we need a solid "nest egg" of funds to make sure vital programs continue after the warbler leaves the protection of the list. That's why Huron Pines has joined the CrowdRise Holiday Challenge to raise $10,000 for the Kirtland's warbler. You can help by donating to the effort between November 18, 2013, and January 9, 2014.

I got a chance to pick the brain of 2013 Michigan Notable Author Bill Rapai, author of The Kirtland's Warbler: The Story of a Bird's Fight Against Extinction and the People Who Saved It, to learn more about this wonderful bird and why it's so important to save it.

The Kirtland's warbler is North America's rarest songbird but the level of fervor it's able to inspire in folks is unbelievable. What is it that's so special about this bird?

Its story. It has an amazing story and a story arc like no other animal. You think about bears, or robins, or whales and--you know--there's not an animal out there that has come in contact with so many interesting people, has had so many tragic episodes, has come so close to extinction and has such a persnickety reputation. It's just a fascinating species to study.

How did you come to write your book about the Kirtland's warbler? What was it that first piqued your interest in the bird?

Well, my mother was a science teacher and I've always been a birder and a conservationist--the apple didn't fall far from the tree there. I was a stay-at-home dad and looking around for something to do, and Dave Dempsey--who was Governor Blanchard's environmental policy advisor and has written several excellent books about conservation and the environment--was thinking about writing a book on the Kirtland's warbler and he had another priority jump to the top of his agenda. So we were chatting one day and he said, "Hey, I want to write a book on the Kirtland's warbler but I can't do it. What are you doing? This is a great time to do it because it's just a fascinating time in its story." I said, "Well, I'll think about it." Even though I was a newspaper guy I had never considered writing a book because the task of writing a book is pretty daunting. But then I began to talk to people and I began to listen to people I respect and I said, "You know what? I can do this, because the more I learn about [the Kirtland's warbler] the more fascinating the story gets."

And that's how I felt when I was reading your book--I didn't know much about the story or the background and it just absolutely sucked me right in. Did you find that, while researching the Kirtland's warbler, you came to have an emotional connection with the bird?

If you ask scientists--you know, they're supposed to be cold-blooded, reptilian people in pursuit of fact--they'll say, "No, of course we don't have any kind of emotional connection because we live only in the world of fact." Well, if you get them on a good day you'll see that these scientists who work in the field on the Kirtland's warbler have become very, very attached to the bird. They respect it a lot, they admire it a lot, they enjoy working with the birds and they look forward every year to seeing certain ones come back that they've seen for years and years and years. So yes, the Kirtland's warbler does mean a lot to me. It's become a big part of my life, of course. My book was named a Michigan Notable Book for 2013 and that put me on a library tour. I've traveled all over the state talking with various library groups and Audubon groups and nature organizations about the Kirtland's warbler. Once you learn about its story you can't help but admire [the bird]. It really is a wonderful little creature.

I've often heard people describe the Kirtland's warbler as being very charismatic.

There's a lot about the bird to admire. It is an attractive bird and it doesn't hurt to be attractive. It has a wonderful song which people can hear from a good distance so they can recognize it even if they don't see it, and the story is one of those things that once you learn about it, once you begin to read about it you say, "Wow, this really is fascinating!" I have grown a great deal of admiration for the Kirtland's warbler simply because it's so plucky. And all those things combined really make it very charismatic.

Can you tell me a story about your most memorable Kirtland's warbler sighting?

While I was working on the book I went up to Kirtland's Warbler Festival [which has unfortunately been discontinued], and there was a couple that had come from Nyack, New York to see the Kirtland's warbler. The husband was a retired guy who had worked in the corporate world and he was trying to make a new career in retirement as a nature photographer, and the wife was an architect and she was very interested in the bird. We went out on the big bus tour to see the Kirtland's warbler and there were fifty people gathered around on this road, and the Kirtland's warbler really didn't come all that close. I said, "Look, in exchange for you taking time to talk to me about why you came to Michigan, I'll take you out to see a Kirtland's warbler happily." So the three of us drove out to this little spot in Ogemaw County where I knew the Kirtland's warbler nested, and we parked the car on this dirt road and had walked probably not even 50 feet up the road when we heard a Kirtland's warbler sing. And so we're standing in the road and I pitched a little bit (imitates Kirtland's warbler call) to see if we could get the bird to come close. It flew immediately into the jack pine tree about five feet away, sat on the edge of the jack pine, threw his head back and sang. And the two people were grinning from ear to ear--they got great photographs, they got great looks through their binoculars, and actually they didn't even need to look at it through binoculars it was so close. It just sat there and sang for about five minutes, happy as could be, and it didn't seem to be bothered by us at all. I thought to myself, "Man, if it were only that easy all the time!"

Before I learned about the Kirtland's warbler I wouldn't have even imagined that there had been so much tragedy, mystery and intrigue surrounding this tiny bird. Your book reads like a suspense novel and it's amazing that it's all true. When you were researching for the book, what was the most surprising story that you came across?

It's difficult to say which was the most surprising because every time I would go to an interview with somebody or I'd go to a library and do some research, I'd run across a story--some anecdote that made the book that much richer. I'd leave the place where I got this information and I'd immediately run to where my car was parked, get out my phone, call my wife and say, "Joanne, you've gotta hear this!" Every time I did an interview or ran across some document, it was just another little piece of the story that got better and better.

Is there one story in particular that really stands out in your mind as being really just a unique part of the Kirtland's warbler's history?

I hesitate to say it but I guess it is the story of Nathan Leopold--the murderer from Chicago--who, after being released from prison after committing a heinous crime, came back to Michigan on at least two occasions to see the bird that he referred to as "my old friend." That's the kind of draw, the charisma, that the Kirtland's warbler has. Doing initial research for the book, I knew the story of Nathan Leopold and his research on the Kirtland's warbler. I ran across the paper that he wrote really early but when I found out that after he was released from prison he came back to see the bird, that just blew me away. He could have happily lived out his life in anonymity in Puerto Rico and just been quiet and stayed out of the way, but he had to come back to see the Kirtland's warbler.

What is your current involvement with the Kirtland's warbler and could you describe the challenges the bird faces and what your role is in helping it overcome those challenges?

It's clear that the Kirtland's warbler is going to come off the Endangered Species List soon. The original plan written for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service called for the population to be considered recovered at 1,000 nesting pairs. Well, we've blown past that. We've got 2,000 nesting pairs--the population has expanded pretty well. And even though it doesn't sound like 4,000 total birds (2,000 pairs) is a whole lot, the population is always going to be small and that appears to be a stable population for the Kirtland's warbler. So it's going to come off the Endangered Species List soon. But when it does come off the list, it needs help. The Kirtland's warbler is a conservation-reliant species--it needs continual human intervention on its behalf. We've taken fire out of the landscape--without fire, jack pine seed cones won't open, so we won't have young jack pines which the warbler needs to nest and reproduce. The other problem is that since Michigan was lumbered over, the parasitic brown-headed cowbird has come in and is now laying its eggs in the Kirtland's warbler's nest and affecting Kirtland's warbler populations. So we need to do two things--we need to continually create new Kirtland's warbler habitat and we need to control the population of the brown-headed cowbird. Well, when the bird is delisted, who is going to do this conservation work on its behalf if that endangered species funding from Washington, D.C. is withdrawn? Well, there's a vision for Kirtland's warbler conservation into the future. [The Kirtland's Warbler Initiative was developed to be the program that helps the species transition from recovery to long-term conservation. The Initiative's success depends on the work of a broad coalition of partners collaborating on the development and delivery of key strategies--two of which include fostering the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance and creating a long-term fund to ensure that there will always be money to do conservation work for the Kirtland's warbler. Huron Pines is overseeing these efforts specifically.] My role in the Initiative is to raise funding, educate people and to help tell the story of the Kirtland's warbler so that they understand why the Kirtland's warbler is important. Even at 4,000 total birds, this is still a small population on the edge of extinction. And it's not just important because it is a species on its own; it's also important to the economy of Northeast Michigan. People come from all over the world to see the Kirtland's warbler--they stay in the motels, they eat at the restaurants and they shop at the stores. This little bird has become an important economic boon for Northeast Michigan.

I understand that you're part of the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance, which is a group of advocates that works hand in hand with Huron Pines' Kirtland's Warbler Initiative. Can you describe in general the types of people who are part of the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance and what your role is there?

Members of the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance are really sort of a broad cross-section. We have teachers, we have biologists, we have conservationists and we also have me as a writer. My role is to use my knowledge to help educate people about the Kirtland's warbler. For example, recently the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance went to [Michigan's state capital] Lansing to meet with state legislators and let them know that the Kirtland's warbler is going to be coming off the Endangered Species List soon, that it is an important part of the Northeast Michigan economy and it deserves to continue to have state support from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. The Kirtland's Warbler Alliance advocates continuing to have land set aside in the state forest, to have biologists actively monitoring the numbers and to have people trapping and taking cowbirds out of the area. [In the future, the Kirtland's Warbler Alliance will also continue to be the group that will maintain focus and consider priorities for the species, and will advocate for the its needs across its nesting range which also includes pockets in Wisconsin and Canada.] As a Kirtland's Warbler Alliance member, it's my job to help spread the word and let people know that the Kirtland's warbler is an important part of what Michigan is, since these birds nest mainly in our state. This has been a great Michigan conservation success story.

When you're spreading the word to people about the Kirtland's warbler and the issues surrounding it, what can a concerned citizen do to help this unique bird as it comes off the Endangered Species List?

What can people do? Between now and January 9th, Huron Pines is having a fundraiser at Crowdrise.com and we're hoping to raise $10,000 to help maintain Kirtland's warbler habitat. Anyone who wants to help can donate. They can also learn more about the Kirtland's warbler through the Huron Pines website, and of course they can buy my book and send my daughter to college. (Laughs)

I was interested to see that you began your book with a quote by Aldo Leopold, the father of wildlife management and a proponent of wilderness conservation and environmental ethics. He said, "The first rule of intelligent tinkering is to save all the pieces." Why did you feel this quote was so appropriate with regard to the Kirtland's warbler?

When Leopold wrote that, he didn't have the Kirtland's warbler in mind, I'm sure--but it's pertinent to the Kirtland's warbler because this bird is an important part of Northeast Michigan's landscape. You walk out into the jack pine woods and you hear the Kirtland's warbler and it does something to your soul. You hear that song--you hear that joyous, happy song--and you don't know what you're missing until you lose it. It's like every summer when the birds sing up until a point then all of a sudden they stop. And it's quiet. Just imagine walking into the jack pine forest someday and not hearing the Kirtland's warbler sing. You'd think, "Wow--something's missing." And something important would be missing from the Northeast Michigan forests, and it would be that joyous sound.

That would be a terrible tragedy to lose that piece of the soul of Michigan. Is there anything else you'd like to add?

Yes. People often say, "Well, why can't the bird adapt? It's not smart enough to be able to adapt?" In Northeast Michigan, the Kirtland's warbler found a refuge in the jack pine barrens. [The jack pine barrens] are not particularly attractive and the soil's not particularly rich, but it's been a safe place for the Kirtland's warbler to call home. Since this safe place is small and these [habitat] conditions are found only in a few areas, the Kirtland's warbler will always be rare because the population will be self-limiting. People will say, "Why can't it adapt to live some other place?" Well, think about the Kirtland's warbler's DNA. It's an old warbler species--more than two million years old--and over the course of 2 million years, it has adapted. The problem is that it needs time--it can't adapt overnight or even over the course of 100 years or so. And this [jack pine habitat] that it lives in now is hardwired into its brain, so we have to make sure that that land is saved and protected. Besides, when you look at that land, it's not really economically viable for anything but jack pines. There's nothing that can really grow on that Northeast Michigan sand soil--it's just nutrient poor. So why not set it aside for the Kirtland's warbler [and the many other species that enjoy this ecosystem, including whitetail deer, wild turkeys and cottontail rabbits]?

Just one last thing I wanted to ask you--I've heard through the grapevine that you're a huge fan of M&M's candy. During your experiences hand-feeding Kirtland's warbler chicks, have you ever tried to slip them an M&M?

(Laughs) No, I haven't. I'm saving those for myself.

Special thanks to Bill Rapai for taking the time to talk all things Kirtland's warbler. You can purchase a copy of his book, The Kirtland's Warbler: The Story of a Bird's Fight Against Extinction and the People Who Saved It, by clicking here.

Don't forget to do your part to protect this rare bird by donating to Huron Pines' CrowdRise Holiday Challenge between November 18, 2013, and January 9, 2014.

Huron Pines is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization and an equal opportunity provider with a mission to conserve the forests, lakes and streams of Northeast Michigan. Learn more about our projects by visiting www.huronpines.org.