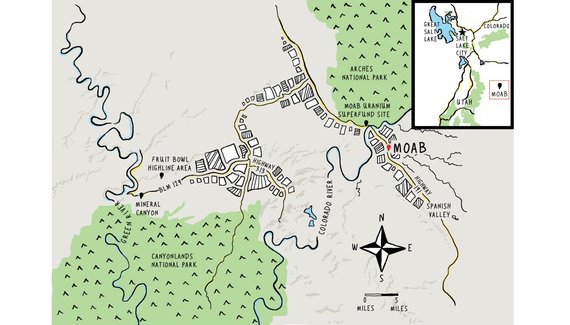

Fed up with tight National Park regulations--no BASE-jumping, no slacklining, no fun!--adventurers are getting cozy with a surprising new advocate: the Bureau of Land Management. Nowhere are the agency's lenient recreation policies on better display than Moab, Utah.

Adam Krum (top) and Nicholas Reyes of Skydive Moab taking flight above canyon country. Photo: Forest Woodward

It was just past dark at the Fruit Bowl highline area, outside Moab, Utah, when the wind came up. The international tribe of roughly 200 slackliners, BASE jumpers, and hangers-on were clustered around half a dozen campfires on the mesa edges, where massive cliff faces drop to the talus below. Embers whipped across the desert. Tents began to roll. And then from somewhere deep in the night came a low roar like a jet engine. Instinctively, we ran toward the noise--me, photographer Forest Woodward, who was barefoot, and his girlfriend, the Canadian climber Jenny Abegg.

The Fruit Bowl is a peninsula in the sky perched some 400 extremely vertical feet above the Green River, about a mile and a half off Mineral Canyon Road and a 50-minute drive from Moab. The scene around it looked like a spring-break campout at a desert lake. Only instead of the water, people had positioned themselves near the gut-churning abyss. On the walls of the bay-shaped chasm are traditional rock-climbing routes. Around its edges are exit points for BASE jumpers. And across its empty center, slackliners had bolted taut at least a dozen lengths of flat webbing that they'd spent the previous two days walking back and forth across, Man On Wire style but without a pole. The shortest, officially called the Cherry, was only 20 feet. The longest, the Lucky Horse Factory, spanned 730 feet. Out in the middle was the centerpiece: a connected pair of giant hammocks hand-woven out of neon parachute cord and climbing rope. The smaller of these "space nets" was in the shape of a four-pointed star and 15 feet across. The larger was a 60-foot-wide pentagon with a circular moon door at its center for BASE jumpers to leap through.

The Thanksgiving event, now in its eighth year, is called GGBY. It stands for Gobble Gobble Bitches, Yeah!, and yes, there's a T-shirt. If you've got a badge and happen to be asking, it's a spontaneous, leaderless assembly, which means it doesn't require insurance, restrooms, or anything else that the Bureau of Land Management--the law in these parts--usually asks of event organizers.

Earlier in the day, Boulder, Colorado, professional climber and bon vivant Timmy O'Neill, 46, had shown the three of us how to traverse out to the larger space net by attaching our climbing harnesses to one of the anchor lines using a flat-webbing pulley called a hangover. "There's no waiver, only a waver," he explained, gesturing "buh-bye" with his hand. Out on the nets with ten other people, including a guy who was playing a seven-foot-long didgeridoo, O'Neill, Woodward, and Abegg hung upside down by their legs. Then O'Neill unclipped his safety line and dangled by his hands. I got a little nauseous watching.

Now past dusk, with partying on the mesa in full swing, it sounded like a rocket booster had ignited below the canyon rim. Investigating the noise, we discovered the nets soaring into the sky. The wind had turned the hammocks into giant groaning spinnakers. Forest, Jenny, and I stopped, and each questioned whether what we were seeing was real or a hallucination. But by then everybody else in the camp was running to the anchors, trying to figure out what to do. The lines had been set to withstand thousands of pounds of force pulling down on them. At the moment, the dynamometers on each line were pointed skyward and whipping wildly back and forth.

At every anchor, a small group had gathered as one would around a disabled car, each person giving unsolicited advice to nobody in particular. We moved from anchor to anchor, listening. The weblocks could work loose! What about edge abrasion? Everybody had a theory. Abegg noticed a theme. "Nobody's in charge," she said. "I have no idea what I'm talking about, but everyone is agreeing with me."

"There are people here who have Ph.D.'s and master's degrees who have IQs north of 150--brilliant fucking people," said a guy from Golden, Colorado, who was standing near an anchor with us.

Abegg said, "There was a guy in a tutu who walked up and drilled somebody's haul bag into the rock--"

"Jeremiah! He knows his shit," a girl from Hawaii assured us.

Was there anybody who knew the intricacies of each anchor and how they all worked together? There was one name people kept repeating. But Sketchy Andy was nowhere to be found.

Just then a bobbing headlamp sailed off from the far side of the cliff accompanied by a wild, ululating whoop. Somebody named Kurt had finally worked up the courage--and a suitably large audience--to zip-line out onto the bucking space net.

Timmy O'Neill, Jenny Abegg, and Martin the Madman logging some Fruit Bowl hang time. Photo: Forest Woodward

This is present-day Moab: former uranium boomtown and current Superfund cleanup site, gateway to two national parks, 1.8 million acres of BLM land, countless miles of singletrack and off-road trails, trad climbing, BASE jumping, slacklining, skydiving, and whitewater rafting, home to 5,100 year-round residents, and annual vacation hot spot for more than two million. I'd come to immerse myself in what I'd been told was either America's most insanely inclusive adventure destination or else a putrid distillation of everything vulgar about public-land use in America--fleets of idling RV generators, swarms of dune buggies, open-air shooting ranges, expensive hunting expeditions, 40-plus BLM campgrounds (usually full), legions of mountain bikers, dirtbag climbers, and #vanlife wanderers seeking the enlightenment that Edward Abbey promised in his 1968 classic Desert Solitaire.

The Fruit Bowl is the epicenter for many of Moab's most colorful figures. Its first highline anchors were bolted in 2008 by a crew that later included the climber Dean Potter, who at the time was experimenting with a parachute instead of a safety leash. Potter once lived in an alcove tucked into a ledge that's now reverently referred to as Dean's Cave. Some of his effects are still there.

The first GGBY was held that same year, at an area near the Fruit Bowl, and for several years was a tiny affair that variously involved naked group highlining, target practice with an AR-15, and the beheading of a live turkey with a samurai sword--all of it, of course, videotaped and available for viewing on Vimeo. In 2012, the festivities moved to the Fruit Bowl, which offers bigger relief and dizzier heights. So far the revelers have avoided death or other serious incident. They also haven't been hassled about a permit, owing mainly to the fact that the festivities take place on a patch of state land just outside BLM jurisdiction.

To find the elusive Fruit Bowl, all one needs to do is Google it, thereby being directed to a very official-looking pin called Fruit Bowl Highline Area. When BLM rangers talk about it, they sometimes refer to it, unironically, as "the highlining resource."

For better and worse, most of what goes on around Moab is made possible by the BLM, which is America's most endowed landlord. Part of the Department of the Interior, the agency manages 246.4 million acres, an area larger than the state of Texas, and has historically been known for conducting oil- and gas-lease auctions and, more recently, jousting with cattlemen fed up with paying $2 per cow to fatten their herds on public land. The National Park Service's colors are green, and when it comes to land-management policy, it leaves the plastic on the sofas so that, as a former Yellowstone superintendent once told me, it can pass the parks along "unimpaired for future generations." The BLM uniform is brown, and its land-use strategy is more akin to how I treat my truck: change the oil and tune the engine but don't worry too much about scuffing the fenders. "We want to make sure that the resources are going to be there for future generations, but we also want to accommodate a variety of uses," says Beth Ransel, manager of the BLM's Moab field office.

It's part of the growing user conflict that has emerged in the past decade, during which the evolving recreation interests of America's adventure class have outgrown what's deemed acceptable among the crowds flocking to the national parks. In February, to mark the centennial anniversary of the Park Service, Imax debuted a new film called National Parks Adventure that illustrates this schism. It features climber Conrad Anker and some friends funhogging around more than 30 parks. For the mountain-biking scenes, however, they couldn't actually ride in Canyonlands. To realize their vision of adventure, the filmmakers shot at Bartlett Wash, a nearby BLM site.

Floating "space nets" lure an international crowd of slackliners and BASE jumpers to the Fruit Bowl. Photo: Forest Woodward

This same scenario plays out all over the West, making the BLM America's laboratory for federal land use and the Moab field office its most dedicated test kitchen. On any given weekend in high season, from March to May, and again in the fall before temperatures dip into the thirties, the agency is the unlikely referee for nearly every activity banned in most parks, including off-roading, BASE jumping, and rope-swinging from natural arches. You'll find dozens of events, some sanctioned and permitted, others merely tolerated. While I was there in November, a high school mountain-bike race held at the Moab Brand Trails had several drones filming the action. I went out with a trail-maintenance crew from one of three local off-road clubs, called Friends for Wheelin', that was repainting and marking the designated trails in hopes of keeping less responsible off-roaders from venturing into virgin desert. And out at the airport, a gathering of several hundred skydivers had received special permission from the BLM to land at sites in the desert.

The BLM's job is, to use its own phrasing, to "protect the resource" and figure out how to get everybody to play nice together. When the BLM banned rope swinging at Corona Arch (Google "Corona rope swing" if you want to flush away a good 15 minutes of your life), it wasn't because there had been a fatality; it was because the area had been designated to have a hiking focus, and the swingers were ruining the ambience.

"There was a situation where we had a human catapult set up over at Mineral that was blocking the roads," says Moab BLM's acting assistant field manager for recreation Jennifer Jones, referring to the iconic S-curve grade that's popular with mountain bikers and jeepers. "So we worked with the people to help them understand that they could not in fact block a road. They were so creative and adept that they modified their human catapult to create a 900-foot vertical zip line, which they BASE-jumped off of."

The divergent land-use philosophies among management agencies have led to some strange conflicts of late. It used to be that only hikers, bikers, off-roaders, and equestrians were going at it over who should be able to do what and where. But the access wars are getting more complicated with the introduction of drones, parachutes, video production, slacklining, and even ultrarunning. For some people, Moab is an escape from those battles: an absurdist experiment in what would happen if we all just did whatever we wanted.

This same scenario plays out all over the West, making the BLM America's laboratory for federal land use and the Moab field office its most dedicated test kitchen. On any given weekend in high season, from March to May, and again in the fall before temperatures dip into the thirties, the agency is the unlikely referee for nearly every activity banned in most parks, including off-roading, BASE jumping, and rope-swinging from natural arches. You'll find dozens of events, some sanctioned and permitted, others merely tolerated. While I was there in November, a high school mountain-bike race held at the Moab Brand Trails had several drones filming the action. I went out with a trail-maintenance crew from one of three local off-road clubs, called Friends for Wheelin', that was repainting and marking the designated trails in hopes of keeping less responsible off-roaders from venturing into virgin desert. And out at the airport, a gathering of several hundred skydivers had received special permission from the BLM to land at sites in the desert.

The BLM's job is, to use its own phrasing, to "protect the resource" and figure out how to get everybody to play nice together. When the BLM banned rope swinging at Corona Arch (Google "Corona rope swing" if you want to flush away a good 15 minutes of your life), it wasn't because there had been a fatality; it was because the area had been designated to have a hiking focus, and the swingers were ruining the ambience.

"There was a situation where we had a human catapult set up over at Mineral that was blocking the roads," says Moab BLM's acting assistant field manager for recreation Jennifer Jones, referring to the iconic S-curve grade that's popular with mountain bikers and jeepers. "So we worked with the people to help them understand that they could not in fact block a road. They were so creative and adept that they modified their human catapult to create a 900-foot vertical zip line, which they BASE-jumped off of."

The divergent land-use philosophies among management agencies have led to some strange conflicts of late. It used to be that only hikers, bikers, off-roaders, and equestrians were going at it over who should be able to do what and where. But the access wars are getting more complicated with the introduction of drones, parachutes, video production, slacklining, and even ultrarunning. For some people, Moab is an escape from those battles: an absurdist experiment in what would happen if we all just did whatever we wanted.

Back in September, on an earlier trip to Moab, I found professional climber and parachutist Steph Davis, 42, and her boyfriend, Ian Mitchard, 35, at a BLM-permitted skydiving event (known as a boogie) out at the municipal airport. Davis, clad in a wingsuit that, unzipped, looked like a cape, was between jumps and organizing wingsuiters into flights.

Unlike many of the town's freer spirits, Davis is pretty squared away. She discovered Moab's Indian Creek climbing area in 1994 while studying at Colorado State University. "When I finished," she says, "I was trying to figure out what I wanted to be, because I'd just moved into my car to climb."

Davis has lived in Moab on and off ever since. She was married to Dean Potter until 2010, but she says their relationship began to unravel shortly after his controversial 2006 climb of the Utah license-plate icon Delicate Arch. The event led to both of them losing their sponsorships with Patagonia. (Potter died in a wingsuiting accident in Yosemite in May 2015.) Despite sometimes climbing without a rope and constantly BASE jumping, she also owns a home in Moab and runs a business. She's noticed changes, even recently, in the BLM.

"In the past five years, they really made a decision," she says. "They were like, We're going to be the voice of reason. We're not going to exclude people. We're not going to judge people. We're not going to save people from themselves."

In 2012, Davis and her second husband, the BASE jumper and wingsuiter Mario Richard, were permitted by the BLM to offer tandem BASE-jumping service. For a brief time before Richard's death in a 2013 wingsuiting accident in Italy, their company, Moab BASE Adventures, was one of two outfits in America where a novice jumper could pay to be strapped to an expert and leap--fully insured--from a cliff.

Like many athletes in the region, though, Davis mostly stays out of the nearby national parks, where rangers routinely arrest BASE jumpers and give climbers the stink eye. "It's like, wait a minute, so you regulate a climber putting a bolt on a rock, but you can pour tons of black asphalt and let the RVs come up and down?" says Davis. "None of it makes any sense. What I appreciate about the BLM is that they try very hard to make sense. We're here. We want to do stuff. So they're not going to lock everything in a glass globe."

In 2015, traffic jams forced a closure of Arches. "The reality is that a lot of Americans only want to drive an RV around a paved loop and say they went to a national park," says Davis. "Whatever. Fine. But then why outlaw the people who are actually going to go on their feet and use the place. What does that benefit?"

It's a common frustration, seeing your low-impact activities disregarded in favor of what the Park Service calls concentrating use--allowing small areas of nature to be destroyed by pavement, sidewalks, jet boats, helicopters, and visitor centers so that millions of visitors can see natural wonders with a measure of convenience. The whole thing can take you to some pretty strange and dark places. It led Davis to make peace with the constant background engine hum of off-road vehicles and buggies in the Moab area. "I recognized that the same rules that allow me to do my thing are what allow them to do theirs."

That live-and-let-live philosophy has a spotty history in Moab, a place personified in the sixties by Ed Abbey, the cranky anarchist who famously railed against the industrialization of the national parks and was especially concerned about the building and paving of roads. "Let the people walk. Or ride horses, bicycles, mules, wild pigs--anything," he wrote in a much quoted chapter in Desert Solitaire called "Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks." "But keep the automobiles and the motorcycles and all their motorized relatives out."

Nearly 50 years later, Moab's Jeep Safari week, put on by Red Rock 4-Wheelers during the days leading up to Easter, is one of the largest off-roading events in the world. And somewhere beneath the roar of all those engines, BASE jumpers, climbers, and all the rest snuck in and colonized the place. "We didn't see it coming," says Moab's mayor, David Sakrison, who's lived in town for 40 years. "I mean, it's like, who the hell wants to jump off a cliff? Trying to anticipate these things is pretty difficult."

Skydiving instructor Adam Krum found Moab during a motorcycle road trip in 2012, just as he was getting into BASE jumping. He'd done two tours with the Marines in Iraq and survived being shot in the head only three weeks into his first deployment, in Fallujah. After his discharge, he worked at the Hershey factory in Pennsylvania and took up drinking in a serious way. But he discovered that skydiving both gave him the fix he craved and kept him broke enough to avoid the bars. "Jumping has been my therapy from the Marines," he said.

Moab takes in a lot of people who don't belong anywhere else. Collectively, it's a mess. Jim Stiles, an old friend of Abbey's and the editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr, wrote and illustrated a book in 2007 called Brave New West in which he decried Moab's rising popularity among adventure seekers. "What's happening today is extractive, too, and in the long run much more efficient and much more destructive," he wrote. "The old miners peeled off the West's skin; today we're removing her soul."

It's natural for the excesses of one generation to irk the one that preceded it. For Moab, the real stress is less about who's doing what and more about the sheer number of people. Moab's sewage facility hasn't been updated in nearly 20 years and is frequently in violation of the Environmental Protection Agency's clean-water standards. The town is designing a new $11 million facility that would support not only Moab but a portion of Grand County, including the RV dumping stations. Residents say it can't come soon enough. At a recent town meeting, city council member Heila Ershadi expressed concerns about the old plant, which was built in the late 1950s. "People smell this intense smell," she said. "But they don't know what they're breathing."

The morning after the windstorm, Sketchy Andy rolled into the Fruit Bowl parking area, his iconic red afro poking out the window of his Nissan Xterra. His real name is Andy Lewis. He's originally from Marin County, California, and if you're

familiar with him, chances are it's because he performed a slackline routine with Madonna at the 2012 Super Bowl Halftime Show while dressed in a toga. Lewis, now 29, is a celebrity around here, and everybody greeted him as he walked the perimeter of the Fruit Bowl, inspecting each anchor. The tents had been restaked, and though at least one empty Bulleit Bourbon bottle was left at an anchor, the tribe had managed to protect the lines. They picked up most of the rubbish that had blown around, too. No sign of human waste, either. It was well buried or else actually packed out, as the BLM had asked people to do. In March, BLM spokesperson Lisa Bryant confirmed that people had cleaned up after themselves but offered a caveat in the form of a written statement. "The number of participants and spectators has grown to a point that there are concerns for resource impacts. The BLM ... may require a special recreation permit in the future."

On his feet, Lewis wore a pair of Five Ten Line Kings, a Rasta-themed shoe designed for doing tricks on taut webbing. He wasn't walking the line that day, but he took a seat on the cliff edge and massaged a rib he'd injured during a hard parachute opening two days earlier. It turned out that Lewis had been reticent to talk because a judge had placed a gag order on him for an incident surrounding a series of illegal BASE jumps from the Three Gossips rock formation in Arches National Park. On May 2, 2014, Lewis had been spotted by rangers making his final jump and was subsequently found hiding in a juniper tree. He was fined, his parachute was confiscated, and he was required to go to court in Salt Lake City, where he was banned from all national parks.

But what really led to the gag order were his profane Facebook posts harassing the arresting officer--a federal park ranger. He published her name and phone number, asking his friends to call and give her a piece of their minds. "I do not like authority in any way shape or form," he told me. The event was almost entirely unpublicized, but the gag order had just expired on November 7, 2015.

Lewis told me that the consequences of breaking the order would have been a year in jail. "I was also on drug charges, because I was caught with a pound of weed and 25 guns at my house next to a church and schools," he said. "It wasn't mine."

Lewis takes pleasure in shocking people. His language is crass. His Facebook page reads like a Beavis and Butthead stream-of-consciousness tribute to Abbey's brand of anarchy. "You know how much money we waste on national parks?" he wrote on his wall in June 2014, before the judge ordered him to shut his trap. "All for the government to pave over and transform our most beautiful and magnificent lands into profitable tourist traps that attract literally millions of people per year. Well I call bullshit."

In person, Lewis is personable and charismatic if still completely unfiltered. At the Fruit Bowl, he acted like a host with 200 or so dinner guests. He shuttled gear out onto the nets for two women who wanted to perform a circus-style silks-and-lyra-hoop act while dangling beneath the net. He dispensed advice and gave directions and group hugs. Lewis is trying to soften his image now, if only a little. Like other Moab types, he didn't so much choose Moab as require it. "Really, I've been annexed to this corner of the world," he says.

In 2013, Lewis had been walking highlines without a leash. His friends, worried about him, told him he needed a safety line. So he tied one onto his penis and walked the line naked. He's had dozens of close calls, many of which he anthologized in "Sketchy Andy's 10 Sketchiest BASE Jumps Ever," a video he posted on YouTube. "That was a crazy time," he says. "Just after the Super Bowl. I'd been getting recognized. For the most part, I made the news with things that weren't cool."

He's even trying to leave his "Sketchy" moniker behind. Lewis has lost a double handful of close friends to BASE-jumping accidents, several around Moab. After Potter died last May, Lewis received more interest from TV producers. "It's kinda weird," he says. "Since Dean died, I've gotten more phone calls than ever. Dean was my hero, the guy who I saw doing this. Now that he's gone, I'm like, Am I going to die soon?" So he's turned over a new leaf, and jokes about rebranding himself as Safety Andy, a name that might give potential clients more confidence in his abilities.

Out in the canyon, the space nets were starting to fill up again with revelers. A pair of drummers set up their bongos near the cliff edge, providing a beat for the two aerialists who Lewis helped get set up. A camo-clad sheep-hunting guide from Escalante Outfitters, who'd been glassing the canyons around the Fruit Bowl for trophy desert bighorns, ambled up to watch. We'd met him the day before, shortly ahead of the windstorm, while we were brewing tea in a small cave at the lip of a tall cliff. "I was down in the valley and looked up and saw all these people hanging out in the sky," he told us. "I had to come check it out." Today he brought the hunting camp's cook as well.

During the course of two trips to Moab, the one thing that struck me about the whole scene was just how well everybody seemed to get along. That and how much fun the place can be. GGBY is on track to become this decade's upstart Burning Man, and yet just ten miles away it's still possible to disappear for weeks into the wilderness of Canyonlands. It gives you an appreciation for the impossible job that land managers have trying to keep the whole thing from devolving into civil war.

Overhead, somebody was filming with a small quadcopter drone. The wind had finally died down enough for BASE jumpers to appear, backpacked and helmeted, at the various exit points along the cliff. Several of them ferried out onto the space net to jump through the moon door. As each person launched, a girl in the net would shout "I love you!" either because she really did or, more likely, because BASE jumping out of an unstable hammock is dangerous enough that it seems worth hedging in case those are the last words the jumper ever hears.

Just then a group of people carrying pieces of a giant steel apparatus walked up and asked Lewis where he wanted the Russian swing set up. The contraption turned out to be a giant human catapult for flinging BASE jumpers a great distance off a cliff. Lewis leaped up and went to help them find the perfect place to put it.

by Grayson Schaffer, Outside Senior Editor