The future of sports may belong to late-bloomers. To a significant degree, it already does.

The latest late-bloomer to make news -- in motion in the green sneakers -- is quarterback Carson Wentz. Last week, Wentz became the second pick in the NFL Draft.

Carson Wentz was a 5-foot-8, 120 pound high school freshman who played many sports. He was not a starting quarterback until his senior year. He did not distinguish himself as an NFL prospect until late in college at North Dakota State.

The Washington Post's Adam Kilgore made a strong case, in this profile, that Wentz has succeeded not despite being a late-bloomer -- but because he bloomed late.

I took that premise to David Epstein, author of The Sports Gene: Inside The Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, for this episode of Wavemaker Conversations: A Podcast for the Insanely Curious.

I encourage you to listen to our entire conversation, in which Epstein provides a perspective-changing road map for young athletes, their parents, and coaches.

Here are a few brief takeaways.

Epstein has synthesized a growing body of evidence that demonstrates the pitfalls of having young kids specialize in a single sport. The physical risk is well-documented:

The number one predictor of adult-style overuse injury in a kid is that they were highly specialized. So they had given up, I think by age 12, all of their sports to focus only on one, and they were doing that sport at least ... nine months a year.

Injuries aside ...

It turns out that what makes the best 10- and 12-year-old team is not what makes the best 20- and 25-year-old athlete. This highly structured approach -- it might work for a sport like golf, where it's very static, and you're just doing the same repetitive movement, and you're not relying on what sports analysts call anticipatory skills, which is the ability to judge a dynamic situation in motion. For the sports that require that, which is almost all of the ones we care about, what you actually want is this sort of broad base of exposure to different types of sports early on, and only in an unstructured manner.

Regarding Carson Wentz, Kilgore writes:

His delayed progression allowed him to develop well-rounded athletic skills and avoid the over-coaching -- and, in some cases, detrimental coaching -- many young quarterbacks receive.

David Epstein finds that the highly structured youth sports system in the U.S. -- with travel teams that reach down into the pre-teen years -- too often fails to identify the Wentzes in our midst -- and regularly disadvantages kids who just want to realize their athletic potential, whether it leads them into college sports or not.

The earlier and earlier the selection starts, the more coaches mistake biological maturation for talent and potential.

So what is the right age to specialize in a single sport? Epstein addresses what he calls that "gazillion dollar question" about 19 minutes into our podcast.

Trainability Rules

David Epstein lived the science of athletic performance before he studied it.

In high school, Epstein, who is not a big guy, played football, basketball, baseball, and did some cross-country and track.

In college, he was a walk-on for the 800-meters -- half a mile.

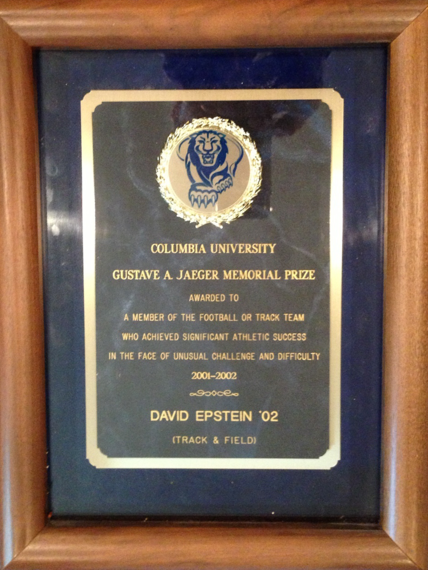

I won my university's award for the four-year athlete who, quote, "achieved significant athletic success in the face of unusual challenge and difficulty." So I have a big glass box with a lion in it.

What was Epstein's unusual challenge and difficulty?

"I stunk when I started."

When researching The Sports Gene, he learned that he was likely what sports scientists call a "low baseline, high responder."

"My physiology starts not well-equipped for the kind of endurance running that I was doing," Epstein tells me, "but that actually has zero bearing on how trainable you are once you find the right training fit for your physiology."

What exercise genetics is showing us is that trainability is the most important kind of talent, and that it might be completely uncorrelated from how good you are, baseline, at certain athletic skills... The ability to improve with the right kind of training and your ability before you start training might be completely uncorrelated. And that's a message that does not get through to coaches who do selection -- whatsoever.

What has David Epstein learned -- from sports science -- about how to discover the right kind of training for a particular individual? He shares his insights on this Wavemaker Podcast.

MICHAEL SCHULDER is the host of Wavemaker Conversations: A Podcast for the Insanely Curious. You can subscribe for free here on iTunes