Last month, to issues regarding cadets at the Air Force Academy being forced to say "so help me God" when taking oaths came up.

The first, which got little media attention, was that cadets were sent an email telling them that if they did not say these words their commissioning oath would not be legal, an obvious and blatant violation of the "no religious test" clause found in Article 6 of the Constitution.

The second, which has gotten and continues to get an abundance of attention, is the cadet Honor Oath -- the oath where cadets vow not to lie, steal, or cheat. This oath began in 1959 as the Academy's Honor Code, and at that time simply said, "We will not lie, steal or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does." In 1984, the Honor Code was turned into an oath by adding the line "Furthermore, I resolve to do my duty and to live honorable, so help me God."

Optionally adding the words "so help me God" is, of course, anyone's right. These words, however, should not be a part of the official oath, where they inevitably lead to situations in which cadets are forced or coerced to say them. Therefore, the Military Religious Freedom Foundation (MRFF) has demanded that the words be removed. This, of course, has caused a media firestorm, and even proposed legislation to prevent the oath from being changed.

The defenders of "so help me God" are claiming that things like this were the intent of the founders and have deep historical roots, and, as expected are using quite a few lies about American history to support this claim -- ironically lying to defend an oath in which cadets swear not to ... um ... lie.

One of these "so help me God" defenders is Jay Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), who, on October 24, wrote a letter to Air Force Academy Superintendent Lt. Gen. Michelle Johnson -- a letter full of lies about American history.

MRFF has also written a letter to Lt. Gen. Johnson.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Lt. Gen. Michelle Johnson

Superintendent, United States Air Force Academy

2304 Cadet Dr., Ste. 3300

USAF Academy, CO 80840-5001

Dear Lt. Gen. Johnson,

You recently received a letter, dated October 24, 2013, from Jay Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ). This letter was on the subject of the words "So help me God" being added to oaths, and contained what Mr. Sekulow presented as historical evidence supporting the inclusion of these words. Mr. Sekulow's historical evidence, however, is full of the same misrepresentations and outright lies found in the revisionist history books that he cites throughout his letter's footnotes.

Mr. Sekulow's letter contains very little on the history of the issue at hand, but relies primarily on unrelated historical claims, which are prefaced by this statement:

"One of the methods used by the Supreme Court of the United States for interpreting the meaning and legal reach of the First Amendment is to examine how early Congresses acted in light of the Amendment's express terms. One can begin to understand what the Establishment Clause allows (and disallows) by examining what transpired in the earliest years of our Nation during the period when Congress drafted the First Amendment and after the states ratified it."

We at the Military Religious Freedom Foundation (MRFF) couldn't agree more that the actions of the early congresses should be looked at in determining the meaning and legal reach of the First Amendment, and also of the clause in Article 6 of the Constitution commonly known as the "no religious test" clause -- the clause that is most relevant when discussing the issue of oaths. The other actions of the early congresses presented by Mr. Sekulow in his letter will also be addressed here, but first let's look at what he has to say about oaths.

Most of what Mr. Sekulow uses to justify the inclusion of "So help me God" in military oaths consists of examples of current oaths containing these words, while deliberately omitting the history of this practice. Why would Mr. Sekulow omit this history? The answer is obvious -- an examination of "how early Congresses acted" on the subject of oaths would reveal that the original military oaths written by the first Congress in 1789 did not include these words. The phrase "So help me God" was not added to the officer's oath until 1862, when the Civil War made it necessary to write a new oath adding a statement that the officer had never borne arms against the United States. The words weren't added to the enlisted oath until a century later in 1962.

The following was the original military oath written by the first Congress in 1789. This oath was actually two oaths, both of which were required for both officers and enlisted:

"I, A.B., do solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) that I will support the constitution of the United States."

"I, A.B., do solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and to observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States of America, and the orders of the officers appointed over me."

Even before the adoption of the Constitution and its "no religious test" clause, our founders did not include the words "So help me God" in military oaths. The first military oath, written in 1775 by the Continental Congress, did not contain the words. Neither did the oath that replaced that oath in 1776. This was the oath written in 1776 by the Continental Congress as part of the Articles of War:

"I swear, or affirm, (as the case may be,) to be true to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever; and to observe and obey the orders of the Continental Congress, and the orders of the generals and officers set over me by them."

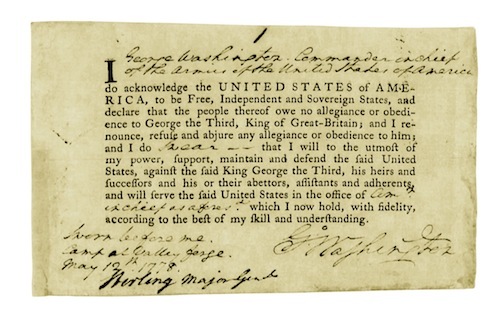

In 1778, the first officer's oath was written. This oath, an oath of allegiance signed by all officers of the Continental Army, not only didn't contain the words "So help me God," but left a blank space for each officer to fill in whether they were choosing to "swear" or "affirm." The following image is the officer's oath, signed by George Washington at Valley Forge on May 12, 1778. After signing his own oath, Washington immediately proceeded to personally administer the same oath to his generals, one of whom, General James Mitchell Varnum, opted to affirm rather than swear.

Rather than include these historical facts about military oaths, Mr. Sekulow cites much more recent sources, such as the several oaths currently found in R.C.M. 807(b)(2) in the Manual for Courts-Martial (oaths which themselves have the words "So help me God" set apart in parentheses to clearly indicate that they are optional) and the current oath of enlistment. What Mr. Sekulow's point is in citing the current use of this phrase is unclear, other than it being a means to avoid the true history of our country's military oaths and the intent of the founders who wrote those oaths.

Mr. Sekulow includes only one historical claim about oaths:

"President George Washington himself added the phrase to the Presidential oath of office when he took it for the first time as our First President."

First of all, it is widely held by historians that George Washington did not add the phrase when taking his presidential oath of office, and that the story is merely a myth that originated in the 1850s with Washington Irving's biography of George Washington. But, whether or not Washington added the words is not important. All that is important is that these words are not included in the official oath as written in the Constitution. Even if Washington did add them, he did so entirely by choice, and not because the words are part of the official, written oath.

Unable to make any historical arguments that are relevant to the issue of oaths, Mr. Sekulow proceeds to diverge into a litany of unrelated historical claims. He points out that George Washington and John Adams issued proclamations for days of prayer (omitting, of course, that John Adams's proclamation caused a riot in Philadelphia because of its mixing of religion and politics, and that Adams himself had to hide in his house for his own safety on the appointed day of prayer).

Then, as expected in any litany of Christian nationalist historical revisionism, Mr. Sekulow zeroes in on Thomas Jefferson, writing:

"Even President Thomas Jefferson -- a man often described as a strong defender of strict church-state separation -- undertook similar actions. In particular, President Jefferson signed multiple congressional acts providing for Christian missionary activity among the Indians."

This claim is completely untrue. Thomas Jefferson never signed a single congressional act providing for Christian missionary activity among the Indians, let alone "multiple congressional acts" as Mr. Sekulow claims.

This popular lie is typically supported by historical revisionists with two types of alleged sources. The first is a series of acts signed by Jefferson that in reality had nothing to do with religion but were merely acts regarding military land grants; the second are certain Indian treaties signed by Jefferson. Mr. Sekulow opts for the lie about the Indian treaties, footnoting his claim with the following:

"See Daniel L. Dreisbach, Real Threat and Mere Shadow: Religious Liberty and the First Amendment 127 (1987) (noting that the 1803 treaty with the Kaskaskia Indians included federal funds to pay a Catholic missionary priest; noting further treaties made with the Wyandotte and Cherokee tribes involving state-supported missionary activity)."

During his presidency, Thomas Jefferson signed over forty treaties with various Indian nations. The 1803 treaty with the Kaskaskia is the only one that contained anything whatsoever having to do with religion, and even that one had nothing to do with promoting "Christian missionary activity among the Indians." No other Indian treaty signed by Jefferson, including the other two used by Mr. Sekulow in his footnote, contained any mention of religion.

When Jefferson signed the treaty with the Kaskaskia in 1803, these Indians were already Catholic and had been for generations. They had begun converting to Catholicism in the late 1600s after a Jesuit priest from France, Father Jacques Marquette, first encountered them in 1673 while exploring the Mississippi River with Louis Jolliet. By 1803, "the greater part of the said tribe have been baptized and received into the Catholic Church," as Article 3 of the treaty signed by Jefferson states.

Lies like this one used by Mr. Sekulow always use words like "Christian missionary" to make it sound as if that Jefferson was trying to convert the Indians to Christianity. Obviously, this was not the case with the Kaskaskia treaty, since these Indians were already Catholic. The support of a priest and help building a new church were among the provisions that they asked for in exchange for ceding nine million acres of land to the United States, not something the government was pushing on them.

As Jefferson was well aware, there was nothing unconstitutional about granting these provisions. This was a treaty with a sovereign nation. It was not an act of Congress as Mr. Sekulow claims. As was made very clear in a lengthy 1796 debate in the House of Representatives on the treaty making power, unless a treaty provision threatened the rights or interests of American citizens, there was no constitutional reason not to allow it, even if that same provision would be unconstitutional in a law made by Congress for the American people.

So what of the other two treaties in Mr. Sekulow's footnote? Well, here he is being completely dishonest about what the source he cites actually says. In no way did Daniel L. Dreisbach say in his book Real Threat and Mere Shadow that these treaties with the Wyandottes and Cherokees involved state-supported missionary activity. This book says the exact opposite. These treaties were mentioned because they didn't contain any religious provisions. What they did contain were provisions for money that wasn't designated for a particular purpose. Dreisbach used these two treaties as examples in a footnote to argue that Jefferson, if he had wanted to avoid listing the provisions for religious purposes in the Kaskaskia treaty, could have done so with a provision that did not specify what the money was for, such as the provisions found in these Wyandotte and Cherokee treaties. So, Mr. Sekulow is not only lying about Jefferson's actions; he is blatantly lying about what his source says to support his lie.

Mr. Sekulow's next claim about Jefferson is also a flat out lie:

"Further, during his presidency, President Jefferson also developed a school curriculum for the District of Columbia that used the Bible and a Christian hymnal as the primary texts to teach reading ..."

This popular lie was concocted by taking the fact that in 1805, while serving as President of the United States, Jefferson was named as president of the brand new Washington, D.C. school board, and then combining that fact with an 1813 report from a school in Washington that was using the Bible and a hymnal as reading texts. The problem with this story? The school in question didn't even exist when Jefferson was president. It didn't open until 1812 -- three years after Jefferson had left Washington.

Mr. Sekulow's footnote for this lie is:

"John W. Whitehead, The Second American Revolution 100 (1982) (citing 1 J.O. Wilson, Public Schools of Washington 5 (1897))."

Here, Mr. Sekulow is citing a revisionist history book that claims to be citing another source. But that source, J.O. Wilson's Public Schools of Washington, does not support the claim made by John W. Whitehead and repeated by Mr. Sekulow. In fact, J.O. Wilson's debunks this claim.

Jefferson had nothing whatsoever to do with the curriculum of any school in Washington, not even the ones that actually did open during his presidency. He was elected president of the school board in 1805 (at a meeting that he didn't even attend), but, according to the minutes of the school board, never took an active role in this position. His only actual involvement was to make a donation of $200 when money was being raised to start the school system.

The Washington school board attempted to establish and maintain two public schools beginning in 1806. These first two schools were the only schools that existed in Washington during Jefferson's presidency. When the city council decided to cut the public funding for these schools in half in 1809, one of the two schools was forced to close. The school buildings had been paid for with private donations, but the school board couldn't afford to pay high enough salaries to hire and keep qualified teachers.

In 1811, two years after the end of Jefferson's presidency, the teacher of a Lancasterian school that had been opened in Georgetown wrote to the Washington school board suggesting that this type of school might solve their problem. Lancasterian schools used a plan of education developed by Joseph Lancaster in England as an economical way to educate large numbers of poor children. By using the older students to teach the younger ones, Lancaster's method allowed one teacher to oversee the education of hundreds of children. The school in Georgetown was teaching three hundred and fifty students with one teacher.

In 1812, the Washington school board decided to try the Lancasterian method. Henry Ould, a teacher trained by Joseph Lancaster in England, was brought over to run the new Lancasterian school.

In 1813, Mr. Ould submitted a progress report to the school board in which he said that the Bible and Watts's Hymns were being used as reading texts. This 1813 report, when anachronistically combined with the fact that Jefferson had been elected school board president eight years earlier, is used to make the completely false claim that Mr. Sekulow makes in his letter -- that Jefferson "developed a school curriculum for the District of Columbia that used the Bible and a Christian hymnal."

Mr. Sekulow also points out that Jefferson "signed the Articles of War, which "[e]arnestly recommended to all officers and soldiers, diligently to attend divine services." It is true that these words were Articles of War when Jefferson signed them, but this really had nothing to do with Jefferson. When Congress decided in 1804 that the Revolutionary War era military regulations needed to be updated, they did so by adding about thirty new regulations but leaving the old regulations from the original Articles of War untouched. So, this regulation about attending church, which actually had more to do with soldiers in the Revolutionary War behaving themselves in places of worship than attending them, remained in the new regulations, the final version of which was passed in 1806 and signed by Jefferson.

Mr. Sekulow's last tidbit of history was actually from the Adams administration, not the Jefferson administration:

"Once the U.S. Navy was formed, Congress also enacted legislation directing the holding of, and attendance at, divine services aboard U.S. Navy ships."

What Mr. Sekulow doesn't mention is that this 1800 law mandating religious services in the Navy, passed by the very religious congress during Adams administration, was protested in the mid-1800s by Navy officers who objected to being forced by the government to attend church. In 1858, these Navy officers petitioned Congress in 1858 to amend this law and make religious services optional.

"By Mr. Kelly: The memorial of officers of the navy of the United States, praying that the act of Congress passed April 23, 1800, compelling commanders of all ships or vessels in the navy, having chaplains on board, to take care that Divine service is performed twice a day, be so amended as to read that the commanders or captains invite all to attend; which was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary."

This issue became part of a widespread, decades-long campaign to abolish both the military chaplaincy and all other government chaplains that had begun in 1848, when the first of what would be hundreds of petitions signed by countless thousands of Americans was received by Congress. Although Mr. Sekulow would probably label the writers and signers of these petitions anti-Christian activists, the first of these petitions, and many of the hundreds that followed, came from religious organizations. The first one came from a Baptist association in North Carolina.

"Mr. BADGER presented the memorial, petition, and remonstrance of the ministers and delegates representing the churches which compose the Kehukee Primitive Baptist Association, assembled in Conference with the Baptist Church at Great Swamp, Pitt county, North Carolina praying that Congress will abolish all laws or resolutions now in force respecting the establishment of religion, whereby Chaplains to Congress, the army, and navy, are employed and paid to exercise their religious functions."

The hundreds of petitions from all over the country that followed this one all said basically the same thing as this first petition from this Baptist organization. And what led to this widespread, national campaign to abolish the chaplaincy in the 1800s? Exactly the same issues that we're seeing today -- forced religion in the military and one form of religion being preferred and promoted by the government.

In Mr. Sekulow's conclusion of the history portion of his letter, he writes:

"As one honestly examines governmental acts contemporaneous with and shortly after the adoption of the First Amendment, it is difficult to deny that, in the early days of our Republic, church and state existed comfortably (and closely) together, with contemporaries of the drafters of the First Amendment showing little concern that such acts violated the Establishment Clause."

Yes, one certainly should honestly examine governmental acts contemporaneous with and shortly after the adoption of the First Amendment, something that Mr. Sekulow clearly has not done in his letter. He has proven himself to be a liar, ironically in a letter supporting the swearing to God of an oath that says "We will not lie."

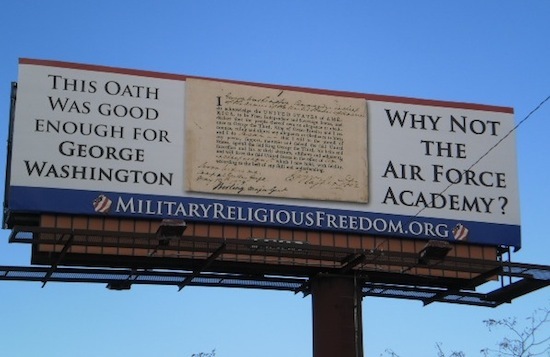

But, all of Mr. Sekulow's history lies aside, the bottom line is that the original military oaths written by our nation's founders did not contain the words "So help me God." If this was good enough for George Washington when he signed his oath in 1778, why isn't it good enough for the Air Force Academy?

Sincerely,

Michael L. "Mikey" Weinstein, Esq.

Founder and President

Military Religious Freedom Foundation

Chris Rodda

Senior Research Director

Military Religious Freedom Foundation

In addition to explaining the real history of military oaths to Lt. Gen. Johnson in this letter, MRFF has put up a little sign near the Air Force Academy as a reminder of the true history of military oaths.