With all the humiliations that Elizabeth Taylor endured at the hands of men both onscreen and off--humiliation that she has been popularly accused of willfully submitting to in her pursuit of the XY chromosome--it takes real gall to hold up the star as a model of proto-feminism in the last years of unchallenged American misogyny. But gall is something of which artist Kathe Burkhart is amply possessed. And it comes fortified with a life-long observation and thoughtful contextualization of the über-celebrity's unfurled life as a celluloid, technicolor, and cinemascopic iconography mirroring half a century of upheavals in the landscape of sex and gender relations.

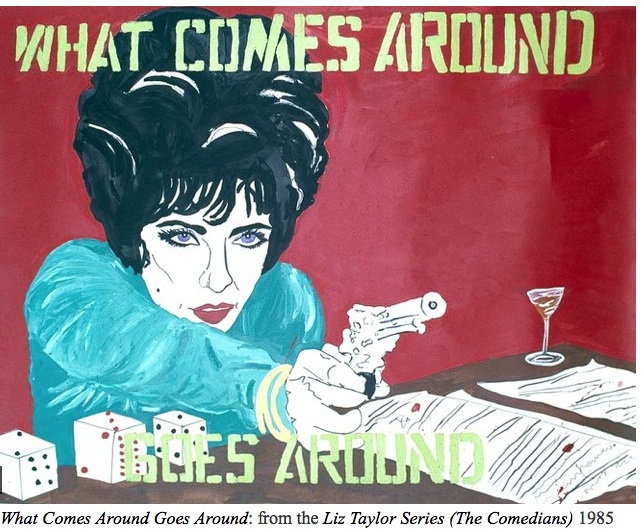

Burkhart--whose Liz Taylor paintings have been shown at MoMA-PS1 in New York; the Stedelijk Museum Zwolle, Netherlands; the Venice Biennale; and the Montehermoso Cultural Center, Spain, and who will be soon featured in solo exhibitions in Amsterdam and Berlin, began her painted parodies of Taylor film stills in 1982. Unfortunately her emergence was eclipsed by the arrival of an international cargo of male neo-expressionist and pseudo-primitive figurative painters--Franceso Clemente, David Salle, Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi, Eric Fischl, Salomé, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Longo, Leon Golub, and Rainer Fetting--many of whom were older and better equipped with international representation. It was perhaps the last significant art movement dominated exclusively by men, and Burkhart found the accolades overwhelmingly stacked in their favor.

That she persevered by adhering consistently to the same pictorial stylization for her singular subject over the next thirty years proves to have been a strategy that paid off for Burkhart in terms of accumulating world recognition for her indelible, if scathing, brand of art. But Burkhart also persisted in employing the medium most conducive to imagining the melodrama of Liz Taylor, "Superstar," while projecting that melodrama against the backdrop of the newly emergent feminist critique of artistic and narrative media and socialization. In an art world where painting is periodically subjected to severe scrutiny by artists and critics favoring conceptual, digital, photographic and sculptural media, Burkhart's Liz Taylor series testifies to the chief reason painting remains vital: for it being entirely and directly dependent on the artists's neurology, and thereby counting as the singular medium for conveying the most interior reaches of subjectivity, emotion, impulse, reflexive and unconscious truth about herself. Yet in turning the medium of subjectivity inside-out to configure an iconography of crassly humiliating scenarios marking out Liz Taylor's sexual celebrity in the West, Burkhart projected her own experience in the art world onto to the altogether arbitrary basis of male domination over the celebrity and commodity machinery that manufactures and sustains (or thwarts and disposes) cultural stardom according to male interests.

Moreover, the subjectivity of painting, particularly painting in the expressionist key, is renowned for conveying behavioral extremes unavailable or unseemly to sculptural, photographic and digital media. Considering that Burkhart took to commenting on the trials and tribulations of a star known for her alternately explosive tantrums and implosive nervous infirmities, Burkhart's recourse to a medium keenly suited to exposing the traces of the actress's trembling neurology proved the crucial component for conveying a notoriously spontaneous and quixotic, if volatile public figure. It also provided the kind of viewer gratification required to sustain her life project at its long, low burn. For Burkhart's painting style, made to look like calendar cast offs for each month of Taylor's (and Burkhart's) passing life, vitalizes the public, if imaginary, conflation of Taylor's sexual indiscretions and provocative filmography. Warhol veered into a similar if uncharacteristically intimate style of drawing early in his career with his Boy Book drawings of the 1950s, but then abandoned the diaristic personal style of observation after introducing his signature Pop appropriations and silkscreen paintings. Burkhart is one of the few artists working today to have taken this Warholian thread and seen it through to its lengthy, multifaceted, and colorized application as Pop observation while converting it to a wholly ovarian political phenomenology.

Burkhart also inserted her art with a considerable measure of sexually snarky cynicism. Yet it is cynicism aimed not at Taylor but at the media so eager to portray, and a public so eager to ogle, a woman of worldly influence dragged through a gutter of sexual and political disparagement. In fact the artist makes a compelling case for Taylor being reconsidered as a pre-feminist woman railing against the male CEOs, producers, directors, publishers and editors overseeing the celebrity industry at the same time she is "made" by them. Taylor's alternately ludicrous yet resilient persona may have impelled more women in the direction of the early "second wave" of feminism than Simone de Beauvoir, Germaine Greer, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Helene Cixous combined. Liz is, after all, almost without peer in having her life unfurled before the cameras around the world. From vulnerable Hollywood ingenue to defiant AIDS activist-pioneer, Liz epitomized for average women around the world the larger-than-life experience and crucial historical placement required to embody and represent the shifting identification of Western women from passive sexual objects to active political subjects. But make no mistake. Burkhart isn't supplying us with a model of a feministly-correct lifestyle.

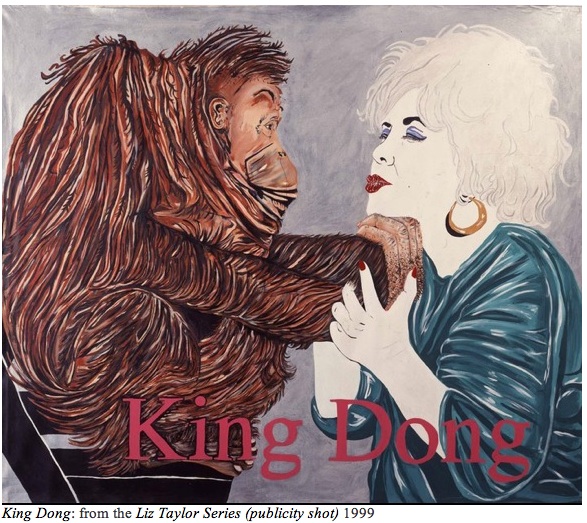

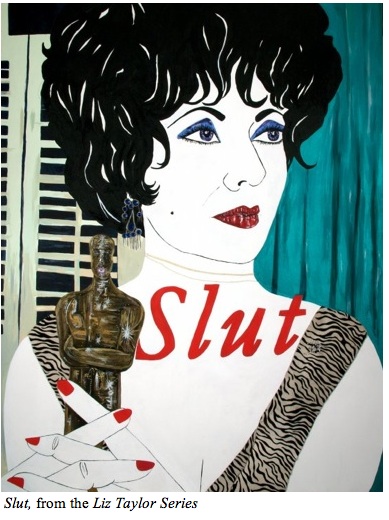

Perhaps it's unnecessary in 2011 to identify Burkhart as a pro-sex, pro-porn feminist, but in 1982 it was crucial to her position, considering that it was a brave stand for a feminist to then take in view of the 1970s and 1980s feminisms that identified all porn as male-identified and antifeminist. Today's multiplicity of feminisms is the end product of women like Burkhart who insist that the choice of uncoerced sexuality and its signification is to be a woman's prerogative and not a movement in lockstep, a position held to be consistent with the principle that "a woman's body is a woman's right" and must be accorded full legal protection. And yet Burkhart wanders farther afield from even the pro-sex feminists to the point that her renderings of Liz present us with pictures of a woman whose open sexual desire and prowress leads to her ridicule as a slut, man-eater, and ball-breaker. Wickedly predisposed to the scathingly profane iconography of bad-girl annihilism at the same time they critically reflect the sexually-obsessed and sexually-phobic visual characterizations of male directors, cinematographers, studio photographers, and paparazzi, Burkhart's paintings elaborate a uniquely defiant mythos around the legendary star. It's a mythos radically departed (if derived) from the creation that the Mad Men of Hollywood, Cannes, Milan, and Madison Avenue would have had us digest in her time. To my mind, we have to look back to the pre-Christian Greeks to find such a hostile valence of iconography conflating the attributes of the monstrously male-devouring harpy with the aphrodisiacally-endowded enchantments of the sex goddess in a single human form.

The fact that we have to circumnavigate three-to-four thousand years of art to find such a primal iconography conflated in the throes of sexual and gender political conflict indicates to what extent Liz represents the radically shifting balance of power back to women in the mainstream culture. By this I mean that Burkhart's paintings hold up a mirror to the Bronze and Iron age art and literature that sought to strip women of the power they are thought to have held in Neolithic times (some four-to-ten thousand years ago) as sacred creators and nurturers of life. Burkhart does this by authoring a modern mythosexual cypher that doubles for Liz, one that both counters and shifts into reverse the progression of male-generated iconography depicting women as monsters and fatalistically seductive sorceresses in a succession of civilizations. In other words, Burkhart represents Liz as a woman who relished her so-called "man-eating roles" with their sado-masochistic inflictions, all the while knowing she was projecting a presence too big and defiant to fit comfortably into the small and disparaging roles that men wrote for women. But just as certainly as the disparaging iconography Hollywood wrote for women inadvertently harkened back to the desperate mythological misogyny of the Bronze Age patriarchies to put women down and instill and perpetuate women's permanent disempowerment, Taylor also reached back to assume the persona of defiant bitch goddess unseen since the rise of Western Christianity. As Burkhart tells the story pictorially, Liz assumed the defiant bitch goddess persona with all the stalwart will, if not always the consciousness and sagacity, of the myriad women of ancient Greece who in legend and art perennially rose up in solidarity to challenge the dominion of men. (Think of the myriad visual representations of amazons, maenads, furies, witches, sorceresses, she-monsters, and harpies who populate Greek art for coming so near (yet ultimately fail) to overwhelming male heroes--and thereby having to be permanently put down by men.)

Equipped with this history and myth in mind, we can begin to see to what extent Burkhart inserts Liz within a transformative iconography reconciling, however disturbingly, beauty with ugliness, revelation and withholding, heroism with wretchedness, sexuality with politics. But in presenting all the many faces of the bitch goddess Liz, Burkhart aptly paints a commentary on the collective male libido that in having its erotic dreamscape both newly projected by modern media and feared through ancient and reactionary morality, sought to humiliate the increasingly powerful and evocative Liz with an array of psycho-erotic movie spectacles and amoral media scandals. It's only decades after, and with the aid of feminism, that we can today see how Liz mirrored a public whipped into a media and brand frenzy by Mad Men savants. By the early 1960s, the public simultaneously gorged off and fed the excesses of the newly eroticized global media, prompting the Mad Men to back Liz into a corner where she would either have to submit willingly as the Western World's sacrificial avatar of male sexual gratification or be outcast (and typecast) as the archetype of the hysterical woman.

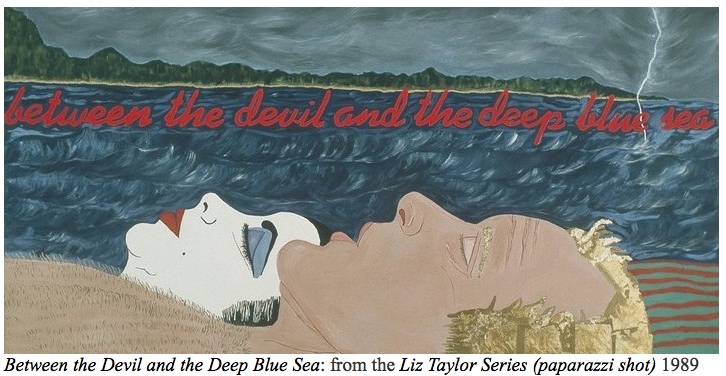

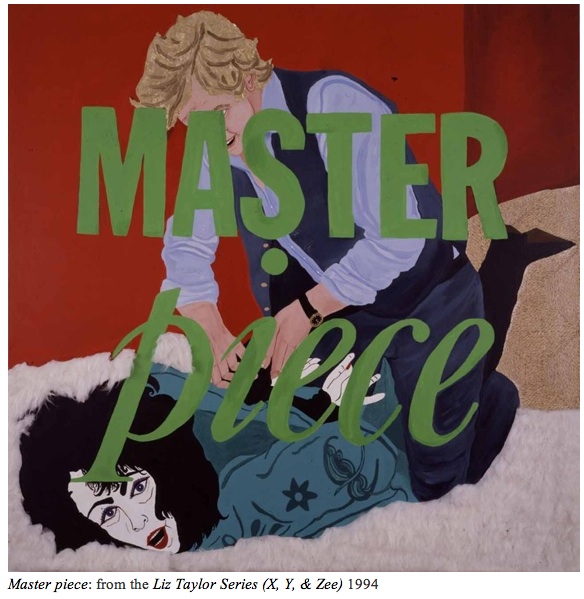

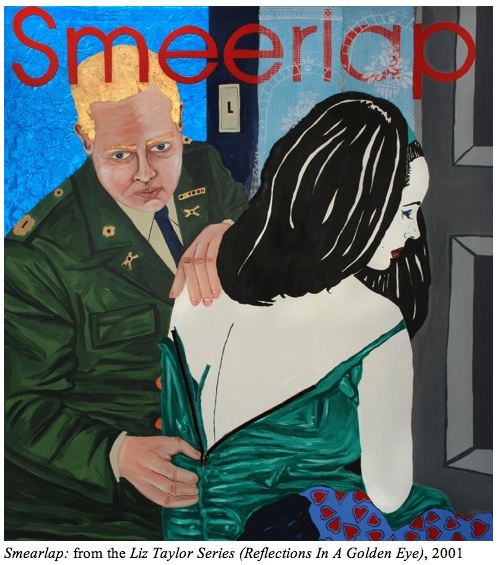

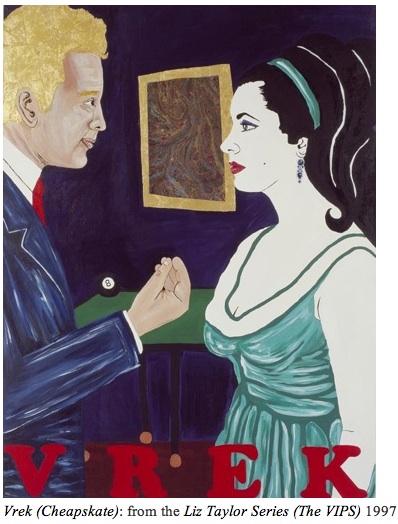

Burkhart's attempt to reconcile the defiant and determined Liz with the Liz who would submit to the male-defined star system accounts for why the artist consistently paints a seemingly unflattering portrait of Taylor. In reality it's the media and it's public that Burkhart disparages, just as it's Taylor's disparagement in the media that bestowed her with so much sociopolitical power in feminist terms. Each painting is derived from a movie still or publicity photo, but in it's rendering, Burkhart heightens the tensions and the demarcations of the sexual conflict either just beginning to simmer or coming to a boil. In this fashion, Burkhart transcends the strategies of appropriation art to index the slowly coinciding evolution and growing awareness of a lone woman star barely ahead of a willful movement of women seeking stardom for all women.

What makes Taylor proto-feminist (that is, intuitively, discreetly, unconsciously feminist) is that no non-comedic Hollywood star before Taylor deconstructed her own glamor and allure to the extent that Taylor did. In life, Taylor dismantled myth after myth projected onto her by the cameras of film directors and paparazzi alike. Once Taylor matured enough to direct her career--and wield her power as an icon--she turned all the publicized victimization and exploitation that she was expected to endure as a starlet to her advantage in the only way a woman could before feminism had advanced to supply the public support system later female stars could at least hope to rely on. And that's by engaging in a sometimes passive-aggressive, sometimes furiously direct sexual warfare with men and their cameras. At least this is the picture Burkhart paints for us time and again.

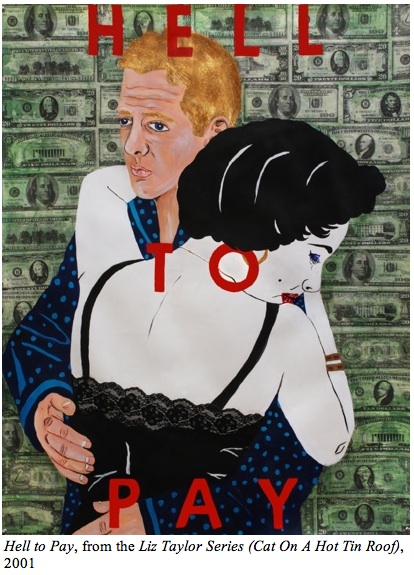

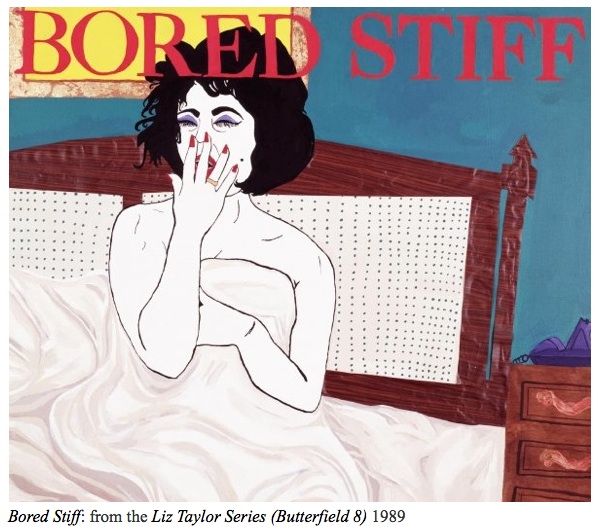

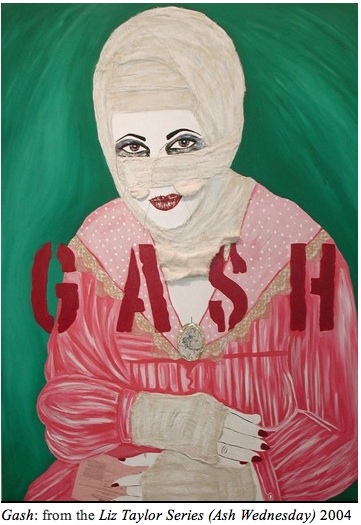

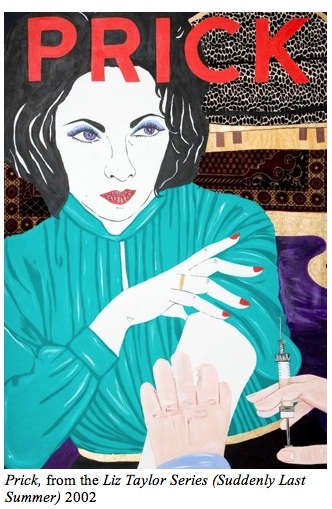

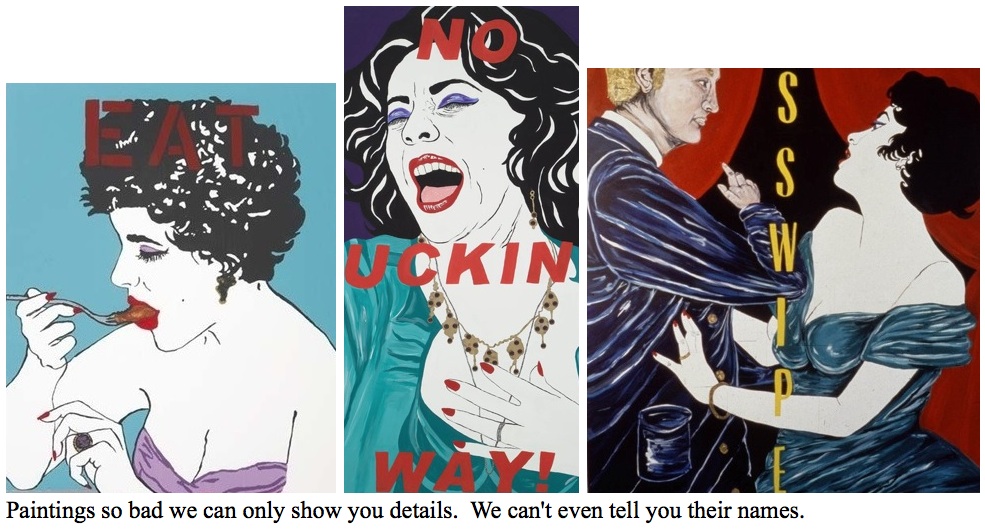

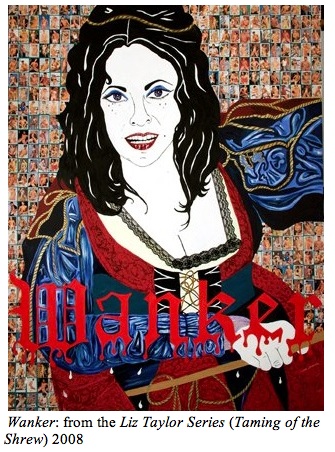

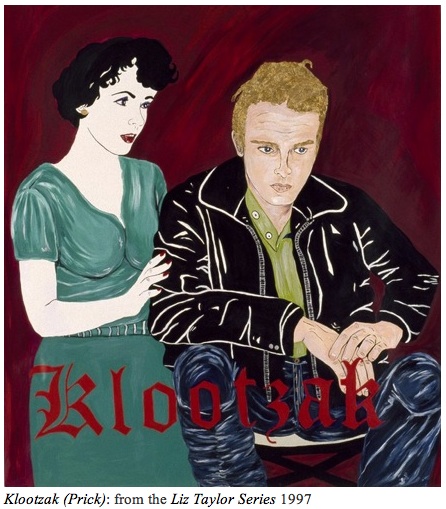

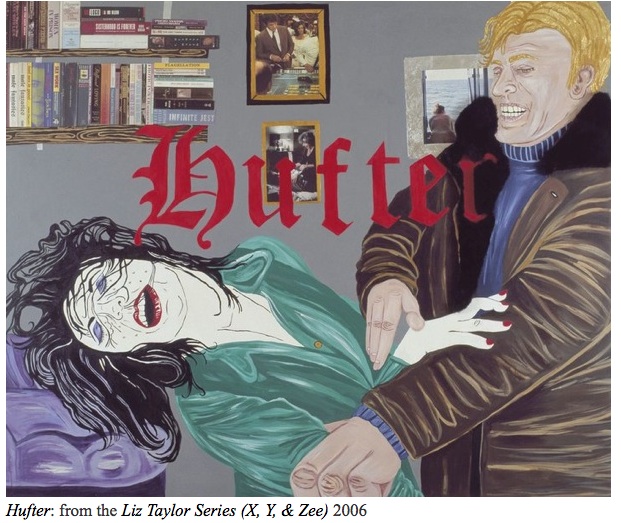

Then there is the added intrigue of Burkhart's paintings playing out a discreet autobiography of Burkhart's life. We aren't cued in on specifics here, and really only Burkhart's former and present lovers might dare to issue an index to the real-life significations of Burkhart's Liz Taylor episodes. What can be ascertained is that autobiographical meaning is one function of the heavy-handed text emblazoning profanity and contempt across many of the pictures. The other is the text's reinforcement of a street feminist's interpretation of the sexual semiotics at hand. For as surely as Cindy Sherman inhabits every one of her "portrait" photos, Burkhart animates the Liz Taylor avatar. But whereas Sherman empties her pictorial self of all true life experience and personality to become the mannequin-persona we delight in, Burkhart pours her life events into the Taylor shell. It's why in the end we read the Liz episodes depicted as respectively pathetic, comic, threatening, empowering. Each painting reflects what Burkhart felt about herself during the passing moment of painting them.

I don't mean that Burkhart's paintings are individual acts of character transposition; Liz remains Liz however she is portrayed. (By contrast, the curiously golden-haired men who ubiquitously inhabit Liz's frames have no real actor-lover reference, and might well signify every heterosexual and repressed-homosexual male.) But in riffing off Liz imagery in the public domain, Burkhart's paintings initiate a viewer-subject fusion; a wish fulfillment; becoming Liz; our reinhabitation of the shells Liz left behind with every motion picture, interview, photo op. In this fashion, Burkhart can be thought of as conducting interventions on the desire, pain, humiliation, volition, ecstasy, and misery that the public imagines to be Liz's life repertoire and thereby projected onto the star. It's an economic conjunction of three lives--Taylor's, Burkhart's, and the viewer's--that we read in each picture. By economic I mean that we get to know all three at once--information about Taylor, Burkhart, and ourselves--by reading what we know about the acts and emotions conveyed through the paintings. We may never really know Burkhart's triumphs and tragedies, but we think we know Liz's. And we certainly know our own.

It's Burkhart's personal correlation with the star that interrupts easy interpretation of the paintings. It's also the catalyst for the ambiguity that invites the scrutiny of feminists. For at the same time that Burkhart aligns with feminist conventions for the representation of pre-feminist and proto-feminist women, she also emotionally bucks the more polemical feminisms by casting Liz in pictorial melodramas that appear to reduce Liz to a stereotypical "asswipe" to men. It's the text emblazoned across the paintings coupled with their laconic humor that signals to us that Burkhart is in fact expanding and converting melodrama to act as a foil to the male interests that identified women with melodrama and thereby cheapened the then-emerging needs of women developing their own unique narratives by condensing "women's stories" into one imaginary, menses-driven and hysterically-acted, hyper-simplifcation.

At face value, Burkhart's paintings depict the conflicting desires of heterosexuality as can be sounded in the feminist key, but without lionizing Liz any more than rendering her as wholly abject, disparaged, victimized--however willingly and fetishistically Liz participated in such depictions. If anything, in participating without reservation in melodrama, Liz (both the real Liz and Burkhart's Liz) consents to her humiliation as an unconsciously motivated and compulsive recipient of male handling. And as an effect of the liberal and open-ended signification of both the Liz persona and Burkhart's personal projection, the work avails itself to non-feminist gaping. But not without leaving men and women both uncomfortable with the oversexed, sadomasochistic, alternately arrogant and abject spectacle Burkhart's Liz "makes of herself." This course of action may seem self-defeating to anyone with a secular upbringing. But to the viewer who has been brought up within one of the world's presiding faiths, self-deprecation through humility, along with the doubt and guilt that produces character swings from imagined holy exaltation to paranoid condemnation is recognized romantically as a portal to a higher consciousness--even one that can be revolutionary. (Think of the Latin American guerillas informed by Catholic Liberation Theology or the Islamic jihadists who resort to suicide bombings.) Whatever we think of the idea of liberation through submission to a higher principle, the motif of humiliation as a virtue has a history spanning millennia and world cultures, and thereby must be understood to account for why it has value as a political means in pre-scientific and analytic circles in general, and Burkhart's Liz Series specifcally.

For the modern, secular rationalist, there is comfort to be taken in knowing that Burkhart's Liz is largely an ironic, theatrical, and allegorical receptacle of various unresolved oppositions, especially those oppositions historically consigned to women of a particularly transgressive character. If one Liz appears ridiculous, it's for her being courageous. If another Liz seems to be caving in to the futility of the absurd, it's while she also can be read as wholly accountable for her actions. If Liz's appetites are conveyed as ravenous, it's because there is always someone (lover, fan, climbing artist, sociopath, stalker) in her presence willing to be devoured. If Liz is made a masochist, it's because her consent gives her power. If Liz is hellbent on self-destruction, it's because self-annihilation is the only recourse to her restless resilience and resistance in the face of male domination and media exploitation.

By convention alone it would seem that such an ambivalence toward, if not fixation with, self-humiliation before emotionally remote and abusive men would make Taylor more a foil to feminism than a prototype of empowerment. But just as Genet and Flaubert saw to it that virtue arose from their characters abject humiliations, Burkhart sees in Liz's mix of willing masochism and aggressive careerism, material acquisition, and sexual prowess, the drive necessary to propel Taylor to the top of the star system in the 1950s and 1960s. It's this personal drive, and the heights to which it took her, that arguably singles Liz out as the premiere populist proto-feminist icon for women and men alike.

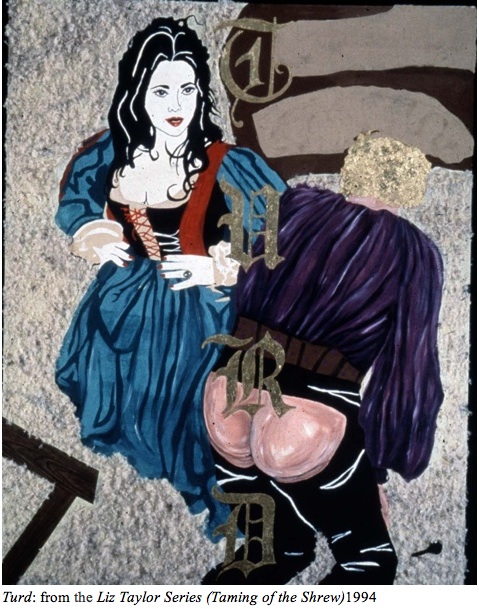

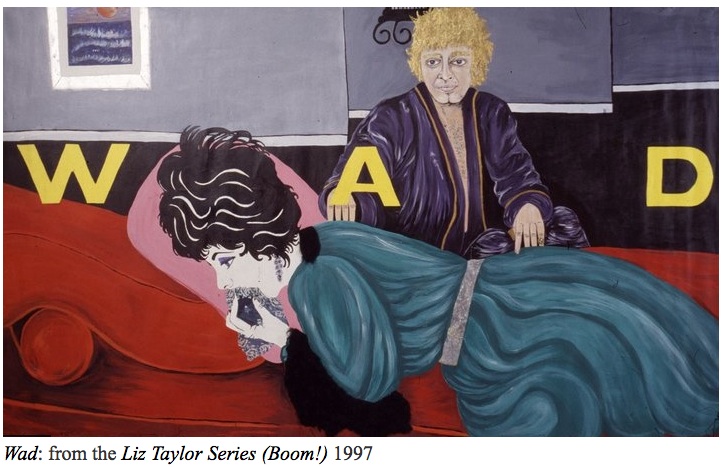

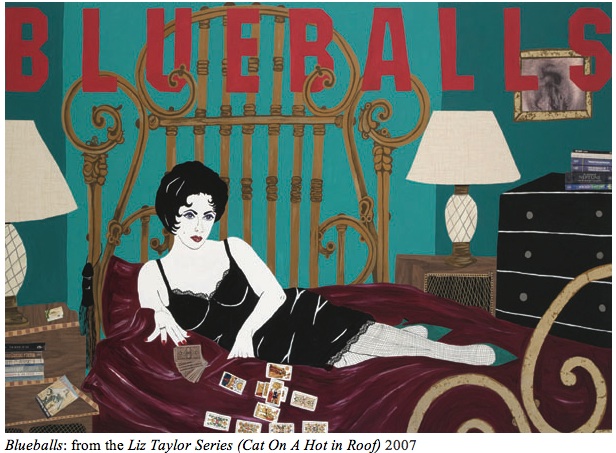

In this sense, Burkhart captures the steel beneath the chiffon, perfume and jewels, the grit that outperforms the pathos, the backbone and driving ambition required to endure the masochism. It's why Burkhart refuses the young Liz the soft-focused lens of her early films as surely as she dispenses a harsh scrutiny on Taylor's white-haired age and infirmities. It's such scrutiny that brings a studied, if harsh, irony to the series Burkhart devotes to Martha from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Katherine of Taming of the Shrew, Maggie in Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, and Gloria of Butterfield 8. In retrospect, Taylor's most renown characters appear not so unlike the Taylor we think we know from the old news reels, LIFE magazine spreads, and National Enquirer exposés, possessed as they are of the combined curiosity and probing intelligence of a relentlessly experimental ingenue who had within her from the start the imperious matriarchal power of a woman who knew she was bitching hot at whatever age she reached if for no other reason than that she always commanded the world's attention.

At a deeper level, the paintings depict roles that for Burkhart embody the pain that comes with the victimization of women at the hands of men at the same time they channel and deflect that pain with the clawing feline defenses that were the only means to women's empowerment before feminism filtered down to Everywoman. I doubt that without Burkhart's paintings I would have ever come to consider the catharsis supplied by such roles accounting for why Taylor never succumbed to the self-pity and self-victimization that felled stars like Marilyn Monroe--though any one of her episodic and famous romantic failures could have led a weaker and less self-realized woman of the pre-feminist era to her demise.

If the Burkhart Liz finds herself perpetually in trouble, it's because she is found defying the conventions laid out for her by men and early, single-minded feminists alike. Contrary to what was for decades perceived to be the prescribed project of radical feminism, namely the depiction of womens' victimization with an actress or role defying the pleasure of men, Burkhart elaborates a complex persona who knows that the pleasure of heterosexual women come in sharing the pleasure of men. If she is punished by men and feminists alike for being too adventurous in her desire, Liz is not the perpetrator. In this respect Burkhart asks as much of feminists as she asks of men. Of men she asks consideration of the reasons they both fear and despise a strong, willful woman. Of anti-sex feminists she asks why they ostracize women who strive to enjoy men promiscuously as if they had not advanced beyond the pre-feminist ostracization of the slut by moralizing puritans.

Burkhart's pro-sex stance is important when considering why the Liz paintings represent stills from Liz's films. For it is in the stills that we can read the narratives and characterizations that logically extend the pictorial and iconographic components into a widely-shared narrative space, replete with all their psychological, sociological, and political ramifications for the pre-femist mainstream American woman. When Burkhart parodies Butterfield 8--a radical film for depicting in its time the life of a promiscuous young woman who has an affair with a married man--we can read young Gloria as that 1960s pre-feminist who equated liberation by The Pill with the liberation of women from the valuation of the slut. Paintings from the Butterfield 8 series take on an even more ironic valence when seen next to paintings from Burkhart's X, Y, and Zee series, which expands on the new promiscuity while reversing Liz's role to now feature her as the scorned wife threatened by her husband's developing affair with a younger woman (the younger woman she was in Butterfield 8).

In her series of paintings parodying the film Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf (and the Edward Albee play from which it's adapted), Burkhart, like Albee, signifies the larger dynamics at play in the scheme of heterosexual relations onscreen and those hidden from view for being buried deep in their psyches. If Albee made Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf as an allegory for the death of the American dream, Burkhart signals the end of the nightmare of abuse rewarding women for enabling men's pursuit of the dream, all the while she sets aside her own dreams for their futility. Except for the post-rape art of the photographer Nan Goldin and the artists Sue Williams and Kiki Smith, it's hard to imagine another feminist artist taking up Albee's themes of marital alienation and brutality, alcoholism, and sexual predation so pointedly. But then the whole point is for Burkhart to rework male artistic social-sexual motifs for a feminist audience by showing Martha's only recourse for a pre-feminist woman wishing to escape the pattern of enabling the vices of men. And what was (is) that recourse? Why, hysteria, alcoholism, and withdrawal--of course.

Cat On a Hot Tin Roof, with it's perrennial Tennesse Williams theme of the inability of men and women to communicate, is natural fodder for Burkhart. I can't think of a single Burkhart painting not centered around the condition of men disinclined or unable to express themselves with women, whether because of repressed homosexuality or our more commonly reinforced homosociality (the code of masculine, violent men; effeminate, submissive women). It's the perennial theme that allows Burkhart to represent the unbridled sexuality of the dissatisfied yet relentlessly desirous, if thwarted, Liz, made in Cat to focus all her energies on a man unable to fulfill her. In Burkhart's hands, Liz is both signifier to the history of gratification denied women and the unavoidably contemporary plight of the "fag hag" who cannot endure leaving the comfort zone of "safe" men to find a man who desires her.

If any Hollywood star embodies the mythological phoenix who rises from the ashes, surely it was the Liz who Burkhart depicts many times over. And for this Taylor remains a model for women everywhere regardless of whether they are or aren't feminist. In this fashion the series functions richly as the potential autobiography of Everywoman. Arguably, Burkhart's Liz series employs the signage of ironic self-deprecation to recall the means to which male-defiant women resorted before they had feminism to reinforce them. In this sense Burkhart's paintings are as much about pre-feminist and feminist history as they are commentary on the importance of Taylor's filmography to the masses from the standpoint of understanding how proto-feminism courses through even the most steeply male-dominated societies.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.